U.S. churches catching on to communion breads free of gluten

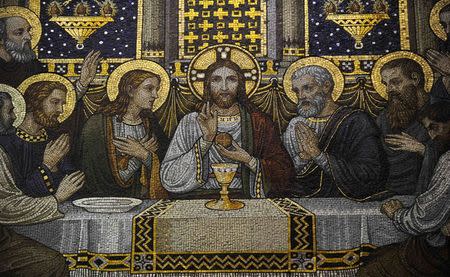

By Colleen Jenkins (Reuters) - Rachel Rieger figured getting diagnosed with celiac disease and having to rid gluten from her diet meant she could no longer partake of the wheat-based communion bread that represents a key facet of her Catholic faith. "It was tough for me to cope with," said Rieger, 23. She was thrilled when her priest in Cleveland, Ohio, told her the church allows a low-gluten wafer generally considered safe for people who suffer damage to their small intestine when they eat the gluten protein found in wheat, barley and rye. The priest would keep one of the low-gluten wafers aside for Rieger when she received communion. Low-gluten and gluten-free communion options are becoming more readily available at churches across the United States, as religious leaders respond to the increasing prevalence of people with gluten intolerance and manufacturers create products that meet most dietary and liturgical needs. Researchers say celiac disease is now four times more common than it was 60 years ago, though many of the approximately one in 100 people who have it go undiagnosed. The autoimmune disorder can cause severe stomach pain, weight loss and fatigue. Sister Lynn D'Souza spent several years helping to create the recipe for low-gluten hosts made by the Benedictine Sisters of Perpetual Adoration in Clyde, Missouri, after hearing from churchgoers unable to take communion due to wheat sensitivities. Sales have increased ever since the nuns began selling their niche wafers almost 11 years ago. They will sell about $150,000 worth of the breads this year, a five-fold increase from the $30,000 in low-gluten sales in 2007, she said. "We continue to get new customers every week, if not every day," she said. Several other distributors also report higher demand. CM Almy in Armonk, New York, has seen sales of gluten-free wafers triple in the past three years, said president Stephen Fendler, who expects another boost after the company last summer began selling the low-gluten version approved for Catholics. Those communion hosts must contain at least a trace of wheat in keeping with the bread used by Jesus at the Last Supper, church officials said. Until the early 2000s, wafers with a low concentration of gluten were mostly manufactured in Europe, making it harder for U.S. churches to get them. But more low-gluten communion breads have come into the American market in the last few years, Fendler said. "Our consciousness of this is definitely being raised," said Father Michael Flynn, executive director of the Secretariat of Divine Worship at the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. "The question that's always kind of a balancing act is how much can you tweak bread and still have it be bread." More education is needed, said Rieger. After moving to the Philadelphia area this year for a job at the National Foundation for Celiac Awareness, she encountered churches that didn't offer low-gluten wafers or didn't realize that regular wafers could contaminate the shared wine cup for celiac sufferers. "It's a little bit trickier when a parish isn't familiar with you," she said. "It's tough to not feel embarrassed or shy about talking about it."