Vancouver food bank potentially risked clients' health through lax alternative-health program

British Columbia public health officials effectively forced the Vancouver food bank to shut down a privately funded alternative-health program offered by a wealthy Alberta oilman's non-profit foundation because it posed a potential health risk to thousands of unwitting Lower Mainland food bank clients.

Internal B.C. government documents show that from February 2014 until late January 2015, the Pure North S'Energy Foundation, funded by Calgary-based businessman Allan Markin, distributed packets of high-dose supplements to thousands of food bank clients with the permission of the Greater Vancouver Food Bank Society.

The decisive actions of the B.C. civil servants contrast sharply with Alberta, where Pure North for years has been allowed to operate similar high-dose programs, focusing mostly on "vulnerable populations" at such places as homeless shelters.

A CBC News investigation found the Alberta government gave Pure North a $10-million grant in 2013 to offer its program to more than 7,000 seniors, despite the fact officials believed the promised health outcomes were not adequately supported by scientific evidence and the program could cause adverse health effects.

3,400 food-bank clients

Internal B.C government documents obtained by CBC News through freedom of information show public health officials determined that more than 3,400 food-bank clients may have received unlabelled, improperly packaged supplements, including vitamin D at a dose higher than the safe tolerable upper intake level recommended by Health Canada — without properly informed consent, counselling or medical supervision.

"This program is a population health intervention that is provided without individual assessments, counselling and monitoring as would be offered in a primary health care setting," states a Jan. 19, 2015 report prepared by public health dietitians for Dr. Reka Gustafson, a medical health officer for the Vancouver Coastal Health Authority.

Two days later, Aart Schuurman Hess, the food bank's chief executive officer and a personal acquaintance of Markin's, suspended the supplement distribution program until a laundry list of health safety concerns could be resolved. But in March 2015, the program was cancelled.

"One of the things that was of real concern to me is this idea that you can bypass the checks and balances that keep people safe," Gustafson told CBC News in an interview. "And you can't.

"The same checks and balances that apply to the person who shops at Safeway should apply to the food bank," she said. "And certainly I would think that most people would expect it to."

Stephen Carter, Pure North's vice-president of communications, said he "strongly rejected" the health officials' contention that the foundation had created a health risk. But he acknowledged Pure North had, in some cases, made mistakes.

"We should have done a better job of making sure that we had followed the rules, and we are doing a better job of making sure that we're following the rules," Carter said. "But in terms of the health of these individuals, we are doing the best work that we possibly can to ensure that these people remain healthy and are healthy for a long time."

Schuurman Hess told CBC News he had never been informed, in writing, by health officials about the program's potential health risks they had identified and, as far as he knows, none of the food bank's clients who participated in the voluntary program suffered any adverse effects.

He said he personally invited Pure North to offer its supplement program at the food banks because he believed it was working well in Alberta and even had been financially supported by that province's government.

Alternative health program challenged

Pure North is a privately run, non-profit foundation that offers alternative, preventive health programs, with a primary focus on preventing chronic disease through high doses of vitamins and supplements, including vitamin D. Pure North claims its program, if broadly implemented, would save governments hundreds of millions of dollars each year in health care spending.

The foundation focuses on vulnerable populations such as the homeless, addicted and elderly. It claims that since 2007 more than 50,000 people have participated in its program in Alberta, B.C. and Saskatchewan.

Obtained through freedom of information, the internal documents detail a concerted effort by B.C. public health officials — spearheaded by a group of dietitians and medical health officers — to methodically identify potential health risks to the food-bank clients and to formulate an "action plan" to address them.

The documents also reveal health officials weren't afraid to confront Markin, the former chairman of Canadian Natural Resources Ltd, the giant Alberta oil and gas company. In 2015, Canadian Business magazine estimated the personal fortune of Markin, who is also part owner of the Calgary Flames, was more than $600 million.

In a Feb. 5, 2015 internal email, Gustafson describes a meeting with the "fantastically rich Alberta 'oil man' " and several Pure North staff.

"We spent a fair amount of time explaining the authority required to practise public health and make recommendations for a population. I am not entirely sure if this sunk in," Gustafson wrote, adding later that health officials had the power to shut down the program if it wasn't done voluntarily.

"We said that we didn't want to mandate them, but that we had the authority under the Public Health Act to do so. (That was kind of fun.)," Gustafson wrote, telling CBC later she was prepared to exercise that authority if the food bank didn't voluntarily stop Pure North from distributing the supplements.

Health risks identified

The internal B.C. documents detail a troubling list of issues identified by the public health officials, including that:

- Pure North employed unlicensed Filipino nurses who distributed packets of high-dose supplements to clients who had not been properly informed about the potential risks.

- Clients were not seen by a doctor and no medical history was taken. Although clients were required to complete a "toxicity symptom list" each month, the forms were not reviewed and no interpretation or counselling was provided.

- Pure North distributed a tablet containing 4,000 IU of vitamin D and 1,000 mg of vitamin C. Manufactured for Pure North, it did not have a natural product number from Health Canada, which is required to verify its strength, purity and safety. Health Canada subsequently issued a compliance letter to Pure North, but did not sanction the foundation.

- The 4,000 IU vitamin D tablet was also distributed without a prescription, which is required in B.C. Pure North admitted it did not know it needed a prescription.

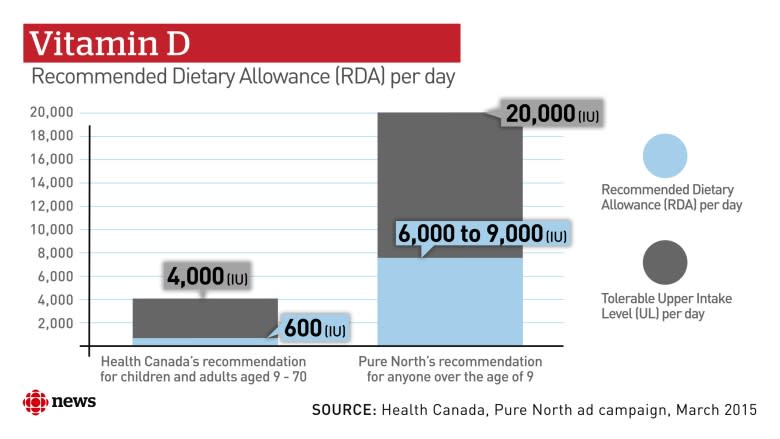

- Clients received a total daily dose of 5,000 to 6,000 IU of vitamin D in their packets. Health Canada's safe tolerable upper intake level for Vitamin D is 4,000 IU.

- Pure North provided clients with a 30-day supply of supplements in clear, sealed plastic bags. The bags contained individual packets that were unlabelled, in contravention of federal regulations. The supplements also were not in tamper-proof containers, a "safety issue for children who may think they are candy."

- Pure North also gave clients a small bottle of iodine drops, which can be toxic in excessive doses.

Health officials were also concerned food-bank clients may not be able to understand the consent form they had to sign before receiving the packet of Pure North supplements, or understand the type of supplements they were given.

Issues rectified

Pure North spokesperson Stephen Carter said clients weren't seen by a doctor, and their medical histories weren't taken, because the foundation mistakenly believed it was distributing vitamin D within Health Canada's 4,000 IU safe upper level. Health Canada's recommended dietary allowances for vitamin D are 400 IU for infants, 600 IU for those aged one to 70, and 800 IU for adults over 70.

Carter said Pure North rectified every issue identified by health authorities. Every participant in a Pure North program in B.C. is now seen by a naturopathic doctor. The foundation stopped distributing the supplement that wasn't Health Canada approved. And documents show the foundation also corrected the labelling and packaging issues.

Before Pure North rectified the safety issues, public health officials, including Gustafson, conveyed several of their concerns in sometimes tense meetings with Pure North representatives and also with food-bank management.

Following one such meeting in January 2015, Schuurman Hess announced the food bank was suspending the program.

On March 5, 2015, Schuurman Hess told public health officials the food bank and Pure North had mutually decided to end the controversial supplement distribution program.

"Both parties thought it better to go their own way," Schuurman Hess wrote in a follow-up email, in which he sought to distance the food banks he oversaw from a wellness program that for nearly a year he had allowed to operate, unfettered, within their walls.

"That way it doesn't affect our services and (standing) in the community. Although we only facilitated (Pure North), the community may consider this to be a food bank program, which it is not."

If you have any information about this story, or for another potential story, please contact us in confidence at cbcinvestigates@cbc.ca

@charlesrusnell

@jennierussell_