'We are very afraid': scramble to contain coronavirus in Mumbai slum

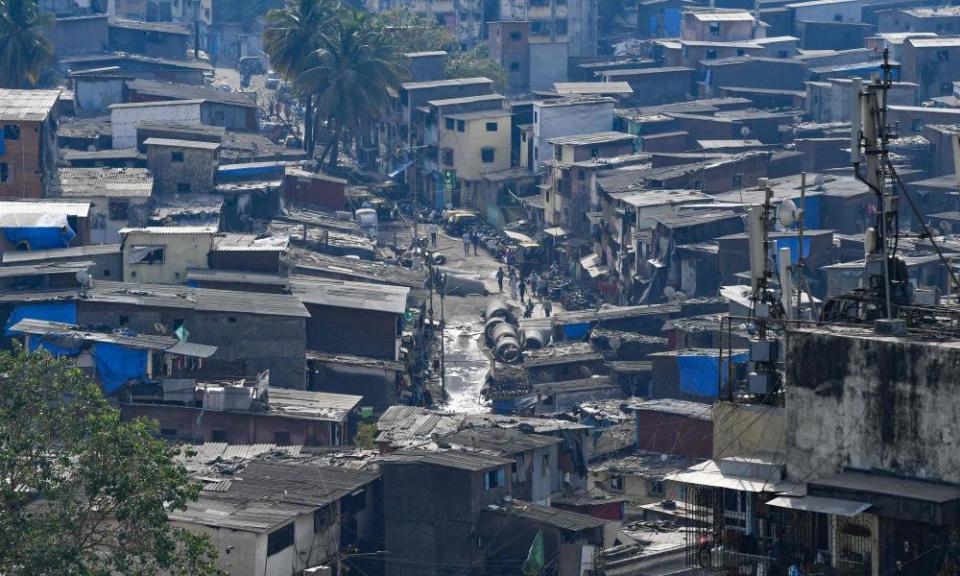

It was the news that many in India had feared. A 56-year-old man who lived in Dharavi, India’s largest slum, where almost 1 million people are densely packed together in a 2 sq km area in Mumbai, had tested positive for coronavirus. He died shortly after.

It has prompted a scramble by local authorities to halt the virus before it takes hold in this overcrowded, unsanitary enclave, which was the inspiration for Danny Boyle’s film Slumdog Millionaire.

But the prospect of attempting to contain transmission in a place where 10 people often live in a single room, more than 80 people share a public toilet and where many houses do not even have running water is already proving daunting to local officials. So far there are five known cases in Dharavi, while 25 people have been taken into special quarantine facilities and another 3,500 placed under home quarantine.

“We are doing everything we can to make sure it does not explode and that there is no community spread, but it is a big challenge to contain this,” said Kiran Dighavkar, the assistant municipal commissioner for G-North ward of Mumbai.

It appears that the 56-year-old garment worker who was the slum’s first victim had made two trips to the local Lokmanya Tilak municipal general hospital over the course of a week, presenting first with a fever and then severe respiratory problems, before he was tested by doctors. With no foreign travel history, he had not been considered high risk. But on 29 March, he tested positive for the virus and died four days later.

There was initial confusion over how this man, who had never been abroad and lived with seven family members in a small flat adjacent to Dharavi, could possibly have contracted the virus. Yet while his family were initially uncooperative, it later emerged he had hosted several men who had attended a religious gathering of the Tablighi Jamaat sect of Islam in Delhi several weeks ago, which has since been linked to hundreds of coronavirus cases across India.

default

The response by the authorities was swift. The area where the victim had lived was sealed off and remains so, and his family was taken into quarantine and all those in the building, or who were considered high risk, have been tested. A new 51-bed hospital in the Dharavi area, specifically to treat coronavirus patients, has also been acquired, with eight intensive care beds, though it is feared if the virus takes hold this will not be nearly enough.

Other cases in the slum include a 30-year-old woman with no foreign travel history, and authorities are searching for the dozens who attended her birthday party a week ago.

“There are already many health issues in Dharavi,” said Dighavkar, who added that one of the main obstacles in tackling the spread of coronavirus was a social stigma that prevented people from coming forward with symptoms.

“But we are hopeful that they have good immunity because they have been exposed to many viruses, especially through using the community toilet, so we are hoping that if we find the high-risk contacts and put them in quarantine, we will be able to control it.”

Babbu Khan, a municipal councillor in Dharavi, said he feared many more people were already infected and warned that undetected cases could “wreak havoc” in the slum, where the disease was likely to “spread like wildfire”.

“For the slum-dwellers it is very difficult to stay safe from a coronavirus-infected neighbour in this incredibly congested slum of Dharavi,” said Khan. “When five people have already tested positive for the virus, there must be many more people around who are already infected. We know that many people carrying the virus remain asymptomatic, but still continue to spread the infection.”

He added: “In Dharavi, 99% of the residents do not have their private toilets and they use public toilets. One seat of a public toilet is used by 50 or 60 slum-dwellers daily. There is a very high possibility that the infection of coronavirus is spreading or has already spread through these public toilets.”

Overall Mumbai has one of the highest concentrations of coronavirus cases in the country and on Monday, three doctors and 26 nurses of Wockhardt hospital in Mumbai tested positive, bringing the total number of cases in the state of Maharashtra to 809.

Within Dharavi, fear has already begun to take hold. Mohammad Shafi Alam Shaikh, 53, who trades in school bags and lives in the MP Nagar area of Dharavi along with his wife and four children, said many people were very scared about the “new disease”.

“Many of my neighbours are very nervous and staying indoors,” he said. “They are coming out of their homes only to use public toilets. All of them say that it is very difficult to escape the infection in such congested slums. They all are afraid of being infected.”

Many mosques in the slum are using their public announcement system to spread awareness about Covid-19. But Shaikh said most of the advised measures for hand-washing and social distancing were an impossibility for the people of Dharavi.

“Many people do not have food at home and so in search of provisions and food handouts, people are being forced to stay outside their homes for a long time. At places like ration shops and free food delivery points people are still gathering in big numbers,” said Shaikh. “So we are very afraid of a fast spread of the virus.”