Victim of released sex offender Frank Skani calls for public warnings

A Burnaby, B.C., woman who was viciously attacked in her home is demanding mandatory public warnings be issued when high-risk sex offenders are released.

"Kate" — not her real name — says no one warned her a violent offender was being allowed to visit a woman staying in her basement suite.

On Aug. 24, 2013, Kate was attacked by Frank William Skani — a man with two dozen convictions, many for violent sexual assault.

"I'm emotionally ready [to talk] now" Kate told CBC News. "I wasn't before."

"The system needs to change. It's inadequate. He was hidden in my basement suite. I didn't even know his name."

Violent attack

Kate was alone in her family's home, cleaning the kitchen in her pyjamas, when there was a knock at the door at 10:45 a.m.

It was Skani, asking if he could borrow some pancake syrup.

When Kate agreed and turned to walk into the kitchen, Skani followed her.

"I could feel him right behind me when I was looking in the pantry," she recalls.

Suddenly, Skani grabbed her from behind, put her in a headlock and threw her to the floor.

"[It was] the most violent, aggressive thing I have ever felt in my life," recounts Kate, her voice wavering. "I thought I was going to die."

As she started passing out, Kate thrashed, hit Skani in the genitals and broke his grip. Her attacker fled — and Kate, in near hysterics, bruised and cut, called 911.

Burnaby RCMP quickly launched a manhunt and apprehended Skani hiding in bushes near Burnaby Mountain.

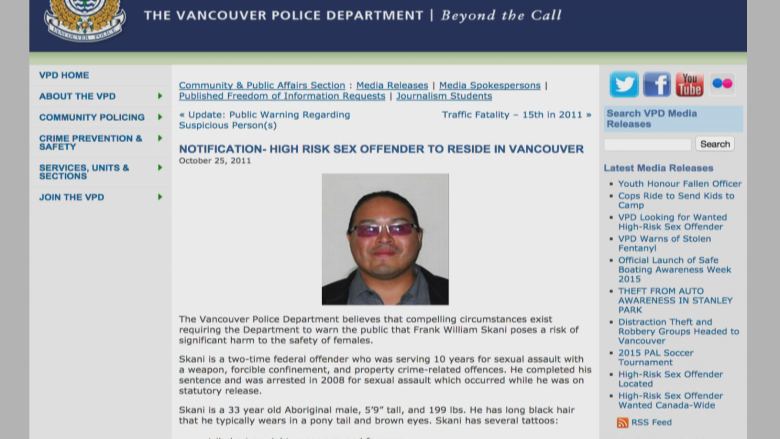

Previous public warning

Skani had been the subject of a public warning by Vancouver police two years earlier, when he had been previously released from prison.

He quickly breached his conditions, was imprisoned for a month, then released. But there was no new public warning that he was out on the streets again — and no warning that he had crossed into Burnaby, where he was being allowed overnight stays with his wife in Kate's basement suite.

"He was on parole. He was supposed to be watched. Why did it happen? Why wasn't I warned?" asks Kate. "It could have stopped it from happening. Maybe if I had seen his face I wouldn't have opened the door."

Kate says that at the time, Burnaby RCMP confessed to her that they weren't notified the violent sex offender had been allowed into their community.

Kate believes the force only found out when Skani attacked her.

Burnaby RCMP would only tell CBC News that when it comes to "monitoring and notifications, we would have to defer to Correction Services Canada."

But Corrections Canada — responsible for prisons and prisoners — told CBC News it could not discuss the specifics of an offender's case, citing the Privacy Act.

Advocates 'horrified,' enraged

Lee Lakeman, a longtime advocate for victims of sex assault, says she's "horrified" by what happened to Kate, but that proper monitoring and supervision of released sex offenders would be a better solution than public warnings.

"I'm enraged.… There's a lot of people involved in this failure. There should have been adequate professional staffing to supervise this man."

A spokeswoman for Vancouver Rape Relief, the city's oldest rape crisis centre, agrees, saying public notification puts too much onus on women to protect themselves.

"My heart goes out to her," says Hilla Kerner. "It's devastating to know that a man who was under state responsibility and supervision was able to sexually assault her.

"There is not enough will, as a result there are not enough systemic policies and expertise in place."

Kate says the public thinks that they're protected — but they're not.

"I was enraged. I still am very upset.… The current legislation is that [public warnings are] optional. I found that mind-boggling. Why is it that these high-risk sex offenders are not being monitored closely? They should be. They are supposed to be."

But Vancouver Police said in an e-mail statement there's only so much they can do.

"[We] continue to monitor approximately 45 high risk sex offenders...We balance a fine line between a person's privacy...and any potential risk to the public.

"Unfortunately... a public warning cannot guarantee that a person will not reoffend..."

Assault vs. sexual assault

There's a final twist to this story.

Skani was convicted of assault in the attack on Kate, but not sexual assault.

Kate says that's because the case was bungled on many levels.

She says she didn't initially report she had been sexually assaulted when police were called because she was traumatized and embarrassed — and because she was interviewed by a male RCMP officer.

"I was an emotional mess. I was all over the place."

Two months later, Kate revealed the attack was sexual in nature. A sex-assault charge was then laid against Skani, but later dropped by the Crown.

And Kate says key evidence — possible ejaculate on her pyjama bottoms — wasn't collected by investigators.

What could have been a five-year sentence for sexual assault was instead reduced to three years for the assault conviction.

Now, minus time served awaiting trial, Skani is scheduled for release in August.

Lakeman is blunt: "That's a failed investigation."

Personal public warning

Kate is issuing her own public warning.

"If this happens again, he could be hidden in another residential neighbourhood, as a tenant, and no one would know he is there," she says. "He is at high risk to reoffend violently or sexually. He will reoffend.

"He's a predator. He preys on people."

CBC's Investigative team is always looking for stories and tips.

Email at us investigate@cbc.ca with your confidential tips