'We've lost our champions': The fight to save Canadian authors

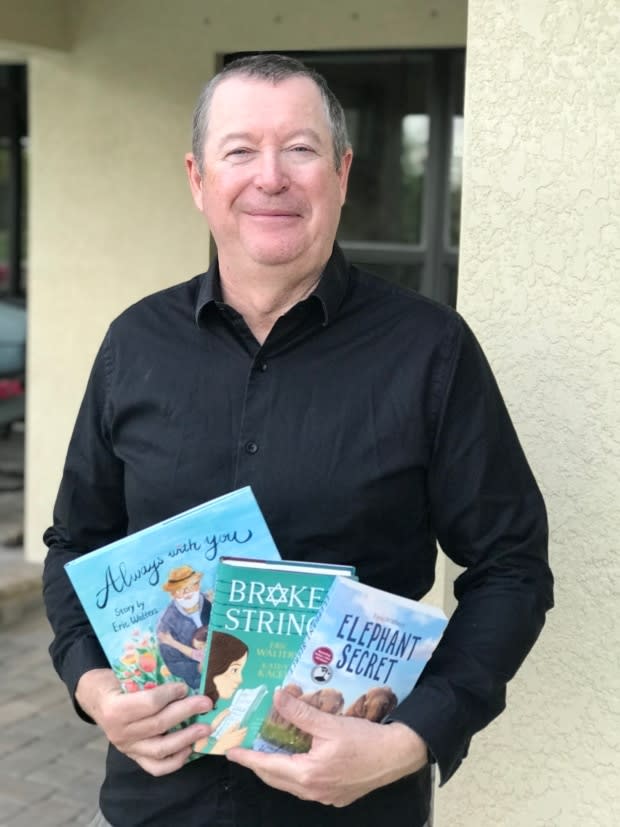

Eric Walters's plot to save Canadian culture came to him much like the idea for a book — in a flash of inspiration.

It was November 2018, and the Toronto-born writer was driving through the Prairies, constantly on the phone with publishers, fellow writers and others in the Canadian literature community.

"And I was getting this real sense of pessimism," said Walters. "There were less publishers publishing less books, and book sales are down. There was a palpable pessimism in all areas."

But the problem wasn't actually people reading less or buying fewer books overall. According to a study on the Canadian book market by the non-profit Booknet Canada, book sales in Canada have held strong: Between 2018 and 2017, the total value of books sold dropped only 0.2 per cent.

What wasn't being sold though, said Walters, were books written by Canadians.

At the same time, interest in Canadian books generally increased, according to a separate 2017 study by Booknet. And demand for Indigenous literature has grown exponentially.

Still, the number of English Canadians buying Canadian-written books has fallen. While Canadians sold 27 per cent of all books in the country in 2005, they stood at 13 per cent in 2018, according to a report titled More Canada.

A children's and young adult writer himself, Walters's solution was to start "I Read Canadian," an annual event dedicated to getting kids to spend at least 15 minutes reading a book by a Canadian author. The inaugural day, on Feb. 19, saw participation from children in schools and libraries in every province and territory.

It's the first step in combating what Walters sees as the root cause of the problem: multinational companies with better resources outcompeting smaller Canadian publishers.

"Because of their ability to produce books cheaper and to flood into the market, they are flooding the market," Walters said. "We are losing touch with our own culture."

Competing issues

Not everyone finds the problem so simple.

While Canadian author Susan Swan believes marketing plays an important factor, she points to the digitization of the publishing field — and some of the software it uses — as a major culprit.

"Canadians do want to read their own books, if they get a hold of them," Swan said. "The interest is there; it's just getting them into readers' hands."

The rise of online book-buying — and its propensity to promote books that are already bestsellers — is an important factor, she said.

What's more, she said, is most large Canadian booksellers and publishers use an American-made software to sort their titles into subjects: A system known as BISAC (Book Industry Standards and Communications).

That system generally works to determine where books go on the shelves, and the more specific an author is when picking their code, the more likely it is their books will find readers.

Though it is used throughout North America, BISAC was built primarily for the U.S. market and reflects those needs more than any other, Swan said. It does not include the ability to differentiate Canadian authors from American ones.

Smaller, independent bookstores and publishers tend to use Canadian-made software, which does indicate where authors are from, she said. But larger outlets rely on BISAC, making it less likely for Canadian readers to encounter Canadian titles.

That doesn't mean the information is impossible for chains to find.

Other classification systems provide information about where authors are from, and BISAC codes have begun to better reflect Canadian interests; Canadian Indigenous poetry was added as a category earlier this year, for example, while the term "Native Canadian" was renamed following complaints.

There are also other systems that categorize all Canadian authors together, Swan said, but they're either not widely used or the information is buried where most don't bother to look for it.

What's more, independent bookstores and publishers have traditionally operated as the primary supporters of Canadian literature, Swan said, but they have struggled compared to larger retailers in recent years.

While multinational publishers and chain bookstores don't necessarily neglect promoting Canadian authors to Canadian audiences, she said, independents often have more of a stake in popularizing Canadian voices, sometimes to the detriment of their bottom line.

"The crux of it is, is that we're in a digital sea change," Swan said. "We've lost our champions for Canadian books, because we've seen a consolidation in the bookstores into chains … in English Canada."

Andrew Wooldridge, a publisher with Canada's Orca Books, agrees.

When choosing what to publish, Wooldridge said he will include a mix of books he believes in — even if they won't sell well — with others he knows will perform better — something he pursues over "every book being strictly viable," he said.

That is something multinationals — who publish 20 per cent of Canadian authors, but make roughly 80 per cent of sales — are less likely to do, he said, especially when it comes to picking Canadian authors in particular.

"On the independent retail side, [independent] stores are more successful at selling Canadian books — they just are," said Wooldridge. "They believe in 'Buy local, sell local' and 'Read Canadian.'"

Multinational publishers

However, that's not a sentiment shared by Vikki VanSickle, head of marketing for young readers at Penguin Random House Canada (PRHC) and a children's author herself.

While she recognizes the struggle of emerging Canadian authors competing with marketing-savvy American publishers, VanSickle says the software isn't to blame. She also rejects the idea that multinational publishers neglect Canadian titles.

While BISAC is largely built for categorization by subject, and not for finding authors from specific regions, VanSickle said the system's codes wouldn't be useful for readers, "because in most cases, that's not how people search for books."

WATCH | Hear more from Eric Walters on creating 'I Read Canadian' Day:

When people search for titles on Amazon or Indigo, they're looking for specific subjects, like adventure or historical fiction. When it comes to promoting writers, "I don't know how often people would search books by Canadian author."

Instead, she suggests, readers will reach out directly to bookstores to ask about local authors or books about nearby regions.

Penguin Random House Canada took part in "I Read Canadian" Day by promoting Canadian books through its social media pages and co-ordinating with authors to share their books with schools and libraries — something VanSickle said is common for them to do.

"I think, sometimes, there might have been a perception in the past that Canadian books can get lost at a multinational publisher. But that's just not true," she said. "It's not the way that we function, it's not the way that we market, and it hasn't been what people are asking us for."

Instead, she said, it's a complex set of factors — fewer print reviews of books, limited space in stores for books to be featured, and a U.S. market that eclipses that of Canada — that have come together to reduce Canadian authors' sales.

Emerging writers at risk

In response to the slump, a number of solutions have been proposed.

"I Read Canadian" Day is expected to return in 2021. Booknet Canada, which has some say in subjects included in BISAC, plans on pushing for more code changes to better reflect Canadian interests. And More Canada's report recommends more funding be given to independent bookstores for promotion of Canadian authors.

Whatever the reason, Swan believes the problem is urgent. If it continues, it will be impossible for younger writers to make their way into the field, she says. Because while the industry is "on a sort of craze to promote emerging writers," these authors don't have a realistic market where they can launch.

She explained that although more books and authors have been published in recent years — a sentiment echoed by VanSickle — attracting an audience as a Canadian writer feels more difficult now than ever.

"It feels shameful," Swan said. "In a self-respecting country, we need to read our own authors."