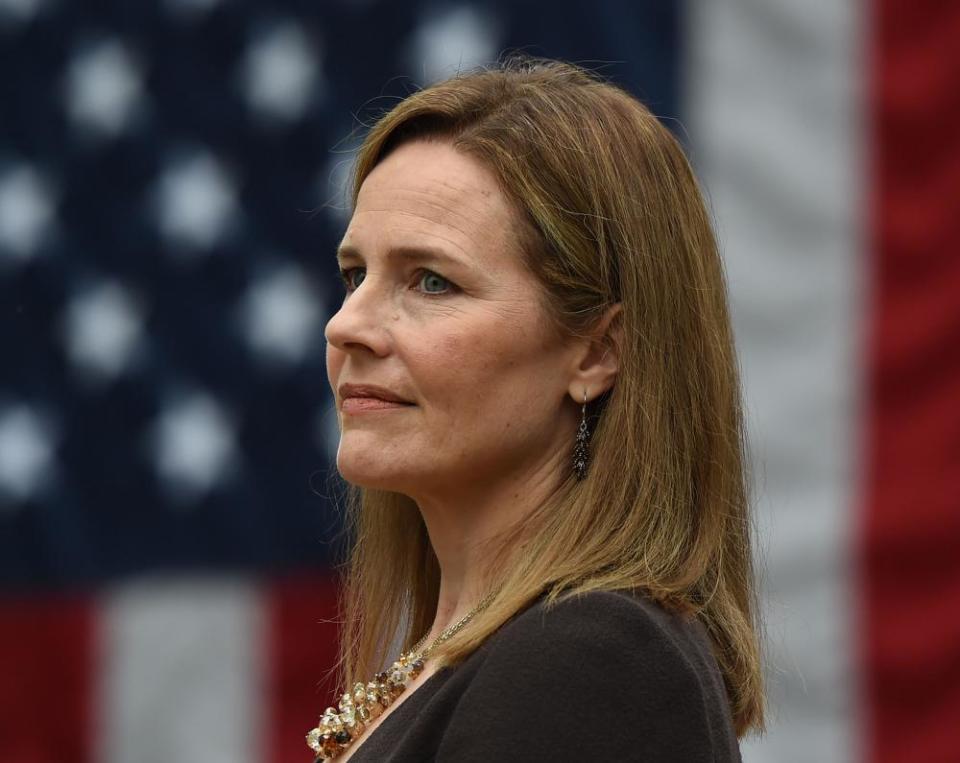

Why Amy Coney Barrett's addition to supreme court may undermine climate fight

The supreme court is shifting right, at a pivotal moment when it could have the last word on how much the US contributes to battling the climate crisis.

Amy Coney Barrett’s addition to the court could leave an indelible mark on how fiercely the US, and perhaps the rest of the world, can fight rising temperatures, even as scientists warn society has just years to take serious action.

Barrett, a 48-year-old devout Catholic, has said she does not hold “firm views” on climate change, calling it a “very contentious matter of public debate”. Because her father worked in oil and gas, she has previously recused herself from cases involving Royal Dutch Shell.

From deciding the legality of climate regulations for polluters to determining whether oil companies should pay for climate damages, Barrett and five other conservative justices will wield considerable influence.

Related: Here’s how conservative the supreme court could tip with Amy Coney Barrett | Mona Chalabi

While Barrett’s history of decisions on environmental issues is limited, her appointment to the court by Trump – as his third justice in four years – solidifies a transfer of power from an often progressive or moderate court.

“Adding one more conservative justice just gives all the conservative justices more fuel to be more political in what they’re going to do,” said Jean Su, an attorney who directs the energy justice program for the Center for Biological Diversity.

Congress has long been too divided to enact significant legislation on climate change. Barack Obama turned to his agencies to write regulations for power plants and cars. His Clean Power Plan for the electricity sector was stalled by the supreme court before it took effect. Republicans say it was executive overreach. Democrats say it was the only way forward.

Sarah Hunt, a conservative attorney who promotes clean energy policy and co-founded the Rainey Center thinktank, said courts should not be settling climate policy.

“It should not matter what Amy Coney Barrett thinks about climate change,” said Hunt, who like Barrett has been a member of the Federalist Society, which has helped seat conservatives on the bench.

“Her entire judicial philosophy, all that she stands for, is about being careful not to legislate from the bench and respecting the role of Congress.”

If Donald Trump wins re-election, the supreme court could be poised to side with his administration on major rollbacks. If Joe Biden is in the White House, the court could shoot down climate standards written by his agencies.

The legal disagreements are unlikely to be about whether climate change is real and a threat. Instead they could come down to whether a president has the authority to write climate rules when Congress has refused to do so.

If one particular case makes it to the supreme court, the justices could decide the fate of millions of Americans – mostly people of color – who live in polluted communities.

Nearly half of US states are challenging the Trump administration’s decision to weaken vehicle pollution standards. The administration has also tried to take away California’s ability to set stricter rules than the rest of the country.

Shana Lazerow, legal director for Communities for a Better Environment, which organizes in California communities surrounded by refineries, highways, diesel corridors and airports, said Barrett’s addition to the court could be devastating to public health as well as the climate crisis.

“The people who will be impacted the most are the low-income communities of color who already bear a disproportionate burden of our society’s industrial activities,” Lazerow said. “Striking down our climate protections is a specific act of racism.”

Even if Democrats take control of Congress and the White House, substantial climate action will be politically difficult. Tommy Wells, the District of Columbia’s director of the department of energy and environment, said cities will be able to do most through local laws.

DC is bringing one of the more than a dozen climate lawsuits from municipalities against oil companies, but states and cities are finding it hard to prove a single company is the direct cause of harm in a specific place.

One of the first cases the supreme court will hear is from the city of Baltimore against major oil companies. The justices will decide what issues can be considered in determining the jurisdiction for climate lawsuits.

“We’ve started having storms and internal flooding even though we’re situated on two rivers,” Wells said. “It will cost the district a lot of money to protect our schools, our utilities, the electric grid – to keep metro from flooding.”