Why COVID-19 testing varies so much across Canada

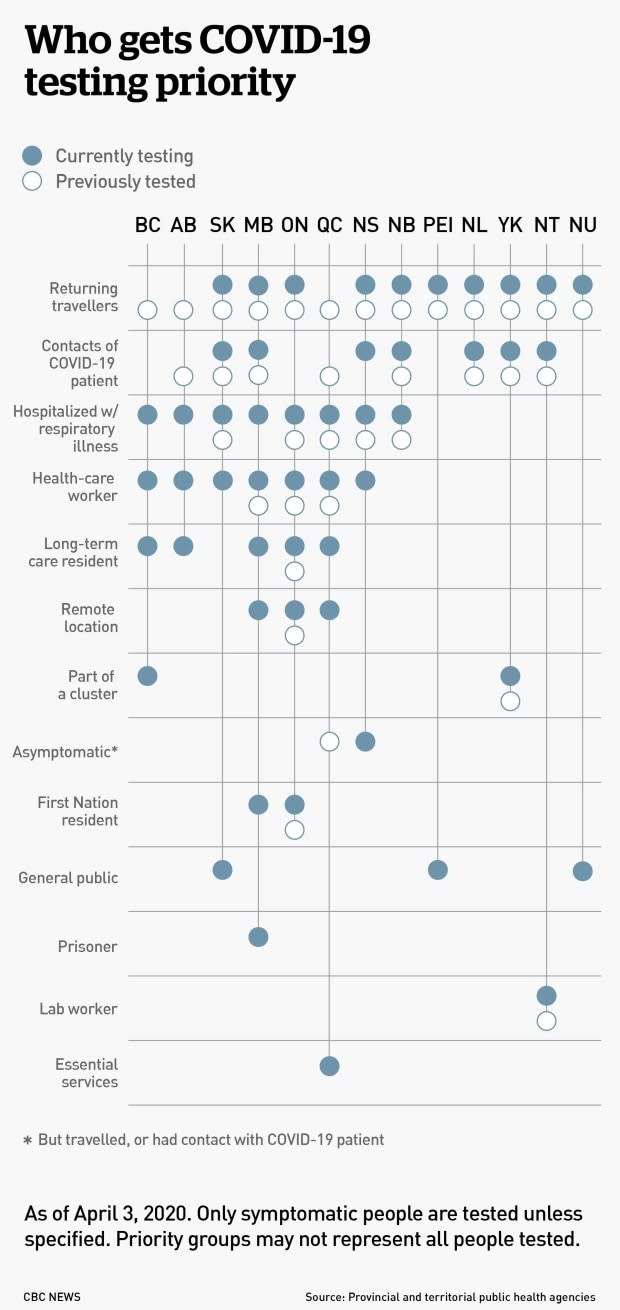

If you just came back from an overseas trip with a fever and a cough, you'll be prioritized for a COVID-19 test in Manitoba and Nova Scotia, but not B.C., Alberta or Quebec.

Some provinces are expanding the groups of people who can get tests as others narrow them — and that may change from day to day. Why? And what does it mean for the accuracy of numbers of infections in different provinces and territories?

Here's a closer look.

How variable is testing across Canada?

Each province or territory has a different rate of testing and different groups that are targeted, sometimes unique to that region. For example, the Northwest Territories lists people who have had lab exposure to biological material, while Manitoba and Ontario prioritize people in remote areas or work camps.

Many don't test people outside those targeted groups, even if they have symptoms, and most even require people within those groups — such those who've been in contact with someone who has tested positive — to have symptoms before they can be tested.

To make things even more confusing, the priority groups change from day to day: Alberta, Manitoba and P.E.I. have all announced changes to their testing criteria in the past two weeks, and Quebec has announced multiple changes in that time.

Why are only certain groups prioritized for testing?

There is generally a shortage of tests, materials needed to run the tests and lab workers to run them. Exactly what is in short supply — and how short those supplies run — varies from province to province and possibly from week to week. That's why some provinces, such as New Brunswick, are running relatively few tests, and some, such as Ontario, have long backlogs.

But to some extent, the shortage is Canada-wide — and worldwide.

"You're just not going to be able to test everybody," said Greta Bauer, a professor of epidemiology at Western University.

That means tests need to be rationed and each province or territory decides exactly which groups get priority, based on two main goals:

Providing appropriate care to those who need it.

Improving the government's response to the pandemic.

As a result, patients who need treatment in hospital are usually prioritized. Those who don't need medical treatment, such as those with mild symptoms, often aren't tested at all — they're just told to self-isolate at home.

"We're going to save the tests for the people who are really sick," said Gaston De Serres, an epidemiologist practitioner at the Institut national de santé publique du Québec and a professor at Laval University, in an interview in French.

And to make sure those people can be properly treated, he said, health-care workers must also have good access to testing to ensure they can continue to safely work with patients.

Many people may think testing — and the daily infection numbers that come from the results — are an important way to measure the spread of COVID-19 in their communities. And more widespread testing would presumably better do that.

But while that is a way that governments might use testing, right now it "is not the primary use of tests," said Bauer.

Why are priority groups changing so much?

Bauer acknowledged testing criteria are changing quickly — something that she called "appropriate" as the pandemic moves through different stages, particularly since a main goal of testing is to improve government response.

"That is, I think, what's driving most of the changes we've seen," she said.

Testing also needs to be responsive to what's happening in different communities, she noted.

Why are some regions broadening their testing?

Initially, most cases across Canada were travel-related, so travellers and their close contacts were prioritized for testing in the hopes that COVID-19 could be contained in the way SARS was.

But now more than half of cases in Canada have been spread through community transmission and the numbers are getting higher, prompting many provinces to de-prioritize travellers.

Some provinces, such as P.E.I. and Nova Scotia, have broadened who they test in a bid to get a better handle on community spread.

Why are others making their testing more targeted?

Many provinces are now facing a shortage of tests and a strain on their health-care systems from COVID-19 infections, forcing them to narrow their criteria.

Alberta, for example, used to test more broadly, but on March 23 announced it would stop testing contacts of someone with COVID-19 and returning travellers to instead prioritize health-care workers, long-term care residents and clusters of cases.

And Quebec has changed its criteria twice in the past two weeks, as it struggles to balance testing shortages and a growing strain on its health-care system with a desire to get a better handle on community spread.

On March 19, the province announced that it would test more widely, and as recently as earlier this week, it said it would test asymptomatic contacts of people with symptoms. But on April 2, Quebec's public health director, Dr. Horacio Arruda, said the province was no longer testing travellers, contacts of people who tested positive and people with mild symptoms.

The province's priorities for testing are now hospitalized patients, people in long-term care, health-care workers, people in remote regions, and first responders, police and other essential services.

"There are lots of practical considerations that determine how the tests are going to be used," said De Serres.

There has been a lot of debate about which groups should be considered priority in Quebec, he said, as the current list is beginning to represent a lot of people.

Who will be the big priorities for testing going forward?

Health-care workers and others who work in health-care settings are getting increasingly important, said Bauer. "And that's because our response to the pandemic depends on those people."

While other people are being told to self-isolate for two weeks if they have any respiratory symptoms, doing that for health-care workers could lead to a severe shortage. We need to know for sure whether they have COVID-19 or a different respiratory illness, she said, and then get them back to work as soon as possible after they recover.

But she said she thinks testing should be broadened to other groups that help to supply essentials to locked down communities, such as those connected to pharmacies, groceries and deliveries of things like food.

"Those are workers who are being asked to put themselves at risk and they are workers who we need on the job," she said. "We need to not just think of essential services as people working in health-care settings."

How do differences in testing change the apparent number of confirmed infections?

"They're a function not just of what's happening with the underlying pandemic, but with what's happening with testing as well," said Bauer.

An increase or decrease in testing, more targeted testing and changes to delays in getting test results can all impact the numbers of positive tests — even if the number of actual infections stays the same.

In a plot of the number of new cases to new tests before and after Alberta made its testing criteria more targeted, there were suddenly a lot more new cases, or positive tests, even while the same number of people were tested.

You can also see a pretty dramatic rise when Quebec removed a requirement to get lab results verified on March 23.

Small delays in getting results can have a big impact on the number of apparent cases, as the disease spreads exponentially; in Canada, it has been doubling about every three days.

For example, in Ontario, tests have been delayed at least four days — the same length of time it takes for the number of cases to double in that province. That means there are about half the number of cases reported than you would expect to see if test results were immediate.

An infected person detected through testing is not typically counted until two weeks after infection anyway, and obviously, only certain groups of infected people are even tested, so testing results are huge underestimates of actual cases.

"We're looking at, you know, multiple cases that are undiagnosed for each one of those diagnosed at present," Bauer said. "We have to remember that what we're seeing is the tip of [the] iceberg. We're seeing cases that have become symptomatic, where people have met testing criteria, [and] enough time has passed for them to have that positive test."

Those are some reasons why epidemiologists like Bauer say hospitalizations and deaths provide a better understanding of the course of the pandemic than test-based reporting of cases.

Given that testing is so varied among the provinces, when it comes to the number of confirmed infections in each province, "we have to remember we're almost never comparing apples to apples right now," said Bauer.