Why full evidence of the plot to kidnap Michigan Gov. Whitmer may never be known

DETROIT – Encrypted apps may keep the FBI from ever knowing if there is more documentation of the plot to kidnap Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer.

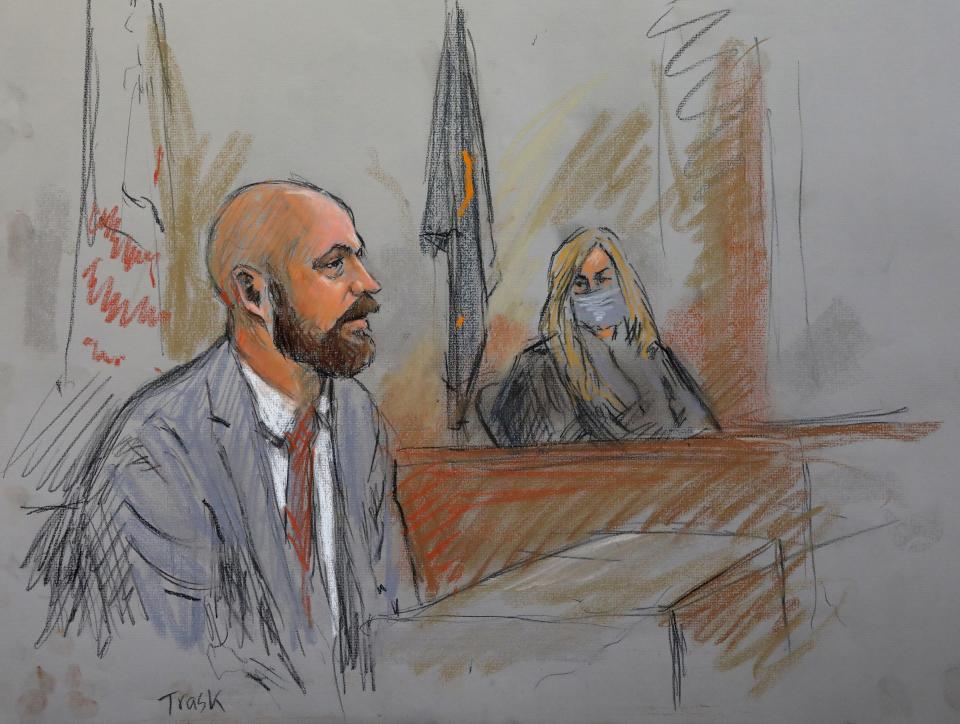

On the second day of a preliminary examination in which sufficient evidence was found to bind five of the six accused men over for proceedings before a grand jury, FBI Special Agent Richard Trask on Friday mentioned the FBI was hindered in its investigation into the group because some data was stored on an overseas server. The communication the FBI was able to enter in as evidence came from a confidential informant.

Technology overall played a crucial role in the planning and formulation of the alleged plot, including the use of Facebook to connect the men, according to an affidavit filed by Brian Russell, a detective sergeant with the Michigan State Police.

FBI: Virginia Gov. Northam was also targeted in plot to kidnap Michigan Gov. Whitmer

In his federal court testimony, Trask mentioned two encrypted apps the group used to communicate and collaborate about the plot: Threema and Wire.

End-to-end encrypted messaging apps are a point of contention between law enforcement and security and tech companies. While companies are called on by consumers to protect user privacy, law enforcement fears sophisticated encryption will hurt its ability to thwart acts of terrorism and other crimes.

In some ways this isn’t a new problem for law enforcement, said David G. Nanz, acting special agent in charge of the FBI in Michigan.

“Encryption goes back to Julius Caesar,” Nanz said.

It's coded messages at its essence. A simplified example of a coded message is shifting every letter in a word one down in the alphabet. An encrypted message sent between devices is coded while in transit, and only uncoded once it gets to its destination. As encryption technology has advanced, it is very difficult for law enforcement to break these codes, Nanz said.

Another term for this type of code is “warrant-proof” encryption, Nanz said. This means the company providing the messaging service can’t turn over the communication records even when it is ordered by the court.

Threema

Threema became popular in 2013 after Edward Snowden revealed the level of data being captured by the U.S. government, said Chester Wisniewski, a principal research scientist with Sophos, a British security software and hardware firm.

At that time, there was very little encryption being used in general on the internet. Popular platforms, such as AOL Instant Messenger, all went through an unencrypted central server — meaning there was a place where the messages could be intercepted and read, that was not controlled by either the sender or the recipient of the message.

In a scramble to find a way to send messages without having them hoovered up by any government spy agency that wanted them, people found Threema, which was one of the few free alternatives with a good track record for protecting people’s data, Wisniewski said.

Since then, three encrypted messaging apps have risen to prominence; Signal, Telegram and WhatsApp, Wisniewski said. One privacy advantage of Threema is it does not require a user to register a phone number to use the app, as is the case with the other three. That appeals to the more privacy-minded user, Wisniewski said.

The servers that operate these services can’t see the messages being exchanged, Wisniewski said. Even if the companies captured the messages for the brief moment the information is passing through its system, it wouldn’t help law enforcement.

“They’re passing through in an encrypted format that's not able to be broken, so it wouldn’t do law enforcement any good,” Wisniewski said. “They’d just get gibberish.”

There is nothing inherently criminal about using apps such as these, Wisniewski said. He recommends everyone use them because it isn’t just law enforcement who might try to access a person’s personal messages.

Deadly discrimination: Asian Americans in San Francisco are dying at alarming rates from COVID-19 and racism is to blame

Wire

Wire is a secured communication and collaboration platform. It offers an encrypted messaging service, file-sharing, as well as a video and voice call service, according to its website.

Collaboration platforms are hard to make fully encrypted because the data files are much larger and encryption takes time to do, Wisniewski said. With smaller pieces of data, such as a text message, it is still hard, but it's much easier than trying to encrypt the work of five different people on a document.

“It’s hard to say whether the messages are fully protected on their infrastructure because they’re not saying it clearly on their website,” Wisniewski said about Wire. “But because they’re not saying it clearly, that tells me that they’re probably not.”

Wire acknowledged in the past it stores some customer data. In 2017, Motherboard pointed out that Wire stores in plain text logs of threads between users. Wire said this was true and added storing the data helps to sync conversations across multiple devices. The company said it was considering ways to change its approach.

More concerns arose about Wire’s security in 2019, when Wire moved its holding company to the U.S., which caused some privacy advocates to question whether U.S. law enforcement would have an easier time accessing user data, according to reporting from TechCrunch. In a 2019 interview, Wire CEO Morten Brogger said the company’s operations were still in Switzerland and that it would still operate under Swiss privacy laws.

In his testimony, Trask did not specify what overseas company held the information the FBI thought would help provide evidence for the plot.

Privacy vs. protection

The FBI isn’t interested in the average person’s messages, Nanz said. Cybersecurity is a central part of its mission, he added.

“We believe there is a way for technology companies to protect their users, but at the same time, you know, when the FBI or other law enforcement has a lawful order to review a device or other communications, we need to be able to do that,” Nanz said.

It is about striking a balance between people’s right to privacy and law enforcement’s ability to access information when it has secured a legal warrant to do so, he said.

People want privacy and they also want the FBI to be able to stop terrorism and child pornographers, all the terrible stuff that gets brought up whenever this topic is discussed, Wisniewski said. To have privacy, privacy must also be given to people who are committing crimes, he said.

“And that really sucks,” Wisniewski said.

COVID indoors: Ventilation and air filtration play a key role in preventing the spread of COVID-19 indoors

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Threema, Wire: Suspects in Whitmer kidnap plot used these apps