Why northeastern B.C. has the lowest vaccination rates in the province — and how that's slowly changing

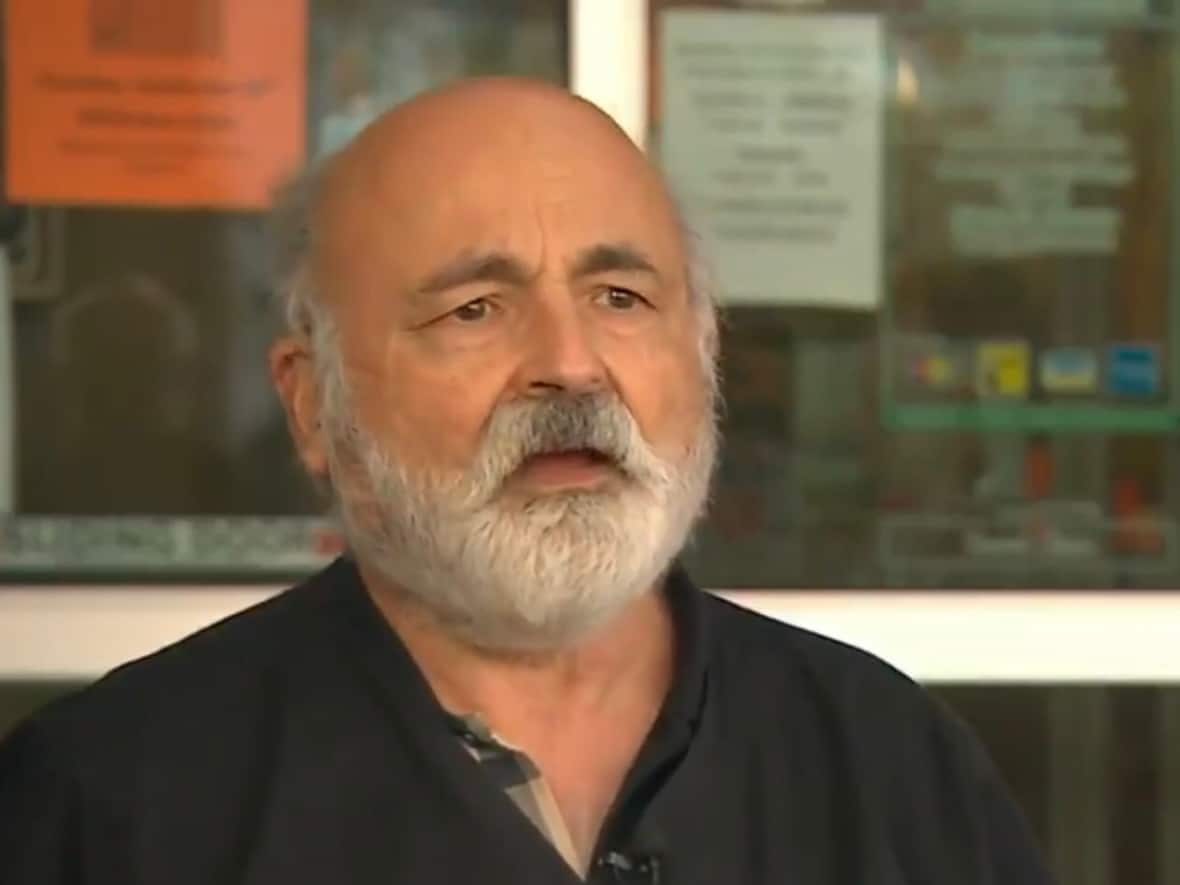

Whenever someone walks through the doors of the Fort St. John Pharmacy with questions about COVID-19 vaccines, Michael Ortynsky prepares himself for a long conversation attempting to convince them to get the shot.

Often, he succeeds.

"They're not anti-vaxxers, they're just frightened," he says of the people he talks to in northeastern B.C. who remain unvaccinated. "They have been getting a lot of half-truths and are very much misinformed about the reality of the vaccines and the pandemic."

Ortynsky says he talks to between two to five unvaccinated people a day, with each conversation lasting around 40 minutes. In them, he tries to address people's fears point by point, without judgment, knowing this might be the first time they are speaking directly to someone with a medical background.

"It's a delicate conversation to have."

And it's an important one: northeastern British Columbia remains the province's most unvaccinated region, with just 55 per cent of residents over 12 counted as fully vaccinated in the Fort Nelson and Peace River North local health areas, and only 53 per cent in Peace River South, compared to 83 per cent for the province as a whole.

Collectively, B.C.'s northeast is the only part of the province where less than 60 per cent of the population has been fully vaccinated.

The result is high levels of transmission and an already stretched health-care system hitting the breaking point.

Over the Thanksgiving long weekend, the province contracted planes to help transfer patients in need of critical care — the majority of whom were unvaccinated people with COVID-19 — out of Northern Health to other regions of the province, reflecting provincial data that unvaccinated people are far more likely to wind up in hospital than those who are vaccinated.

"People are becoming severely ill, even young people, mostly unvaccinated younger people, and hospitals are pushed to the limit across the north. This is directly related to vaccination rates," Provincial Health Officer Dr. Bonnie Henry said Tuesday, reiterating her message that the best way to slow the spread of COVID-19 was for more people to get vaccinated.

But while many people have already taken up the call some, particularly in B.C.'s northeast, are still reluctant. CBC spoke to several residents of the region to find out why they believe vaccine rates are so low — and what can be done about it.

An 'independent streak' — with consequences

One factor that came up repeatedly was the image people in the northeast have of themselves as being highly independent from the rest of the province, from which they are separated — not just culturally but also physically — by the Rocky Mountains.

Many residents say they feel more kinship to Alberta and even Saskatchewan than they do to Victoria and tend to look at top-down government orders with skepticism. Even the clock reflects this: When most of the province started observing daylight saving time, the Peace River region opted to stay on mountain standard time year-round.

WATCH | Why many people in Fort St. John are reluctant to get vaccinated

For some, this attitude goes back generations. Draft dodgers from Alaska attempting to avoid conscription in the Second World War and the Vietnam War settled in the Peace region, as did religious communities attempting to avoid mandatory public education in Manitoba and Saskatchewan after the First World War.

Trudy Klassen, who was raised in a Mennonite community in the Peace region and still has relatives there, counts her family as among those ranks. Her family moved to B.C. after first fleeing Russia, and later to Saskatchewan, to avoid government intervention in their lives.

"The reason they live in the north is to get away from government dictates," she said.

Klassen said it's not just religious communities that feel that way, but also those who work in agriculture or the region's oil and gas fields. People in the north, she said, often feel government policy is a hindrance rather than a help, with a widespread belief that wealth generated in the area funds projects in the rest of the province, while local needs get put on the backburner.

"They're disenfranchised from the rest of B.C."

Ortynsky said while this independent streak helped attract him to the region in the first place, he now worries it is resulting in people resisting public health advice and putting themselves and their community at risk.

"They question things and, troublingly, there are too many opportunities for people to spread disinformation in that environment," he said. The result?

"Some very good people I know are no longer with us," he said.

Indigenous population

The northeast also has a higher proportion of Indigenous residents than other parts of B.C. — according to Stats Canada, approximately 15 per cent of people in the Peace and 22 per cent of people in Fort Nelson identify as Indigenous, compared to six per cent provincewide.

Data from the First Nations Health Authority (FNHA) shows that while vaccine uptake has been high among Indigenous elders, Indigenous people under 50 are far less likely to have been vaccinated than those in other categories and that this difference is particularly pronounced in the north.

Dr. Shannon McDonald, acting medical director of the FNHA, said the reasons behind not getting vaccinated could range from a distrust of government among residential school survivors to people simply not having had the time to get to a clinic due to irregular work shifts or living in remote communities, and she is working with Northern Health to better meet the needs of Indigenous populations.

Standing up to threats

Another factor that may be contributing to lower vaccine rates is a hesitancy among leadership and members of the general population to speak up in favour of public health policies — possibly because of threats of violence for doing so.

Bob Zimmer, the Conservative MP for the region, has not spoken out in favour of vaccination, instead focusing on people's ability to make up their own minds and, until recently, most municipal leaders have been relatively quiet on efforts to promote vaccination.

Peace River South MLA Mike Bernier has been a vocal advocate for vaccination and public health policy and, as a result, says he's received multiple threats and even had protesters come to his home while he was eating Thanksgiving dinner.

Businesses have also faced violence: In November, a Dawson Creek Walmart employee was assaulted by a customer refusing to wear a mask, and in March, RCMP were called to a local No-Frills to arrest Kevin C. Johnston, who had been invited to the city by local anti-mask activists.

Johnston — who incites his followers to disobey public health orders — filmed himself refusing to wear a mask in the grocery store and then getting into an altercation with the store's manager. He was later arrested on charges of assault and is awaiting trial, while also getting set to serve 18 months in prison for violating orders associated with a conviction for hate crimes.

In that environment, some businesses have expressed concern about enforcing public health orders. Last week, Fort St. John RCMP arrested a woman who became belligerent after being told to wear a mask in two different businesses, and local restaurants have reported having their pages flooded with negative reviews for enforcing orders around vaccine cards.

Even the local arts scene reflects this fear: Fort St. John's Peace Gallery North is currently exhibiting a display of pro-vaccine works by an artist who wanted to remain anonymous because she feared blowback.

But curator Richard Bell said he's been heartened by the response to the work, which has been overwhelmingly positive.

"There are a lot of pro-vaccine people but they aren't really as vocal," he said.

Mandates making change

But Bell said that seems to be changing as the province's rules around vaccine cards come into effect. Anecdotally, he said, more people are getting vaccinated in order to attend arts events or play in local sports leagues, and speaking up about their decision.

Those changes are being reflected in provincial data, too. Health Minister Adrian Dix said that since introducing the vaccine card mandate, Fort St. John has seen the biggest increase in the proportion of the population getting vaccinated, and Dawson Creek has also made gains.

The biggest change, however, could be still to come: Last week, B.C. Hydro announced that every worker and contractor at the Site C dam — which employs more than 4,000 people in the region — will need to be fully vaccinated in the coming weeks.

A similar mandate has come from Canadian Natural Resources, which owns the rights to more oil and gas wells in the region than any other company.

Ian King, a control mechanic who spends much of his time at remote worksites in B.C. and Alberta, said those mandates have had an even bigger impact on people he knows than the prospect of not being allowed to go to movies or restaurants.

"There's nothing quite like the possibility of losing some or much of your income to focus the mind," he said.