Why Peel region residents are being credited with saving lives

When Darlene Fournier rushed to help a man whose heart had stopped during a recreational volleyball game earlier this month, she didn't have time to think about anything other than what to do to get the man breathing again.

But it would have been perfectly understandable if she had flashed back 18 years ago, when, in just her first year of teaching, a student in her class collapsed and she had to perform CPR. That student did not survive.

The incident at Chinguacousy Secondary School on the evening of March 2 had a happier ending, with the male patient now recovering well at home. But in both cases, Fournier credits CPR training and easy access to an automatic external defibrillator, or AED, for the comfort of knowing that in both instances, she did everything that she could.

"In both instances, there was a sense of, at the end of it when you are processing it, everything that could have been done was done," Fournier, head of physical education and family studies at Chinguacousy, told CBC Toronto. "I felt that way 18 years ago given the resources we had at that time, and I felt that way three weeks ago."

Fournier's actions were among a dozen incidents in Peel Region between March 2 and 9 where bystanders jumped in to help people suffering from cardiac arrest.

Peter Dundas, chief of Peel Regional Paramedic Services, said Tuesday that public education campaigns about the importance of CPR, and the increasing prevalence of AEDs in the community, are helping residents become more comfortable with the idea of acting when an emergency arises.

"I think that we're seeing a gradual increase in people becoming more confident in the ability to be able to do CPR, especially with introducing compressions-only CPR where people don't actually have to do the ventilations," Dundas said. "Just doing good solid compressions 100 times steady, hard and fast on a patient is all we expect them to do."

Peel paramedics deal with about 1,200 cardiac arrests each year, according to Dundas, and about 80 per cent of them occur at home. That means there are 20 per cent that occur in public spaces where the public can step in to help.

And the importance of AEDs to patient survival has led to new research that says busy coffee shops and bank machines are ideal places for AEDs.

In Peel Region, for example, there are more than 1,000 registered defibrillators in public spaces, including civic buildings, schools, long-term care facilities and rec centres, Dundas said.

According to paramedics, 11 of the 12 patients had recovered a heartbeat before they were transported to hospital.

Paul Snobelen, community safety program specialist with Peel paramedics, said that statistic shows the importance of a quick response. In each case, what Snobelen called the "chain of survival" was followed: "early recognition, early 911, early CPR, early AED."

'It was very confusing'

It's both training and the accessibility of AEDs that are helping to save lives, and the incident on March 2 is the perfect example of all of those lifesaving elements coming together.

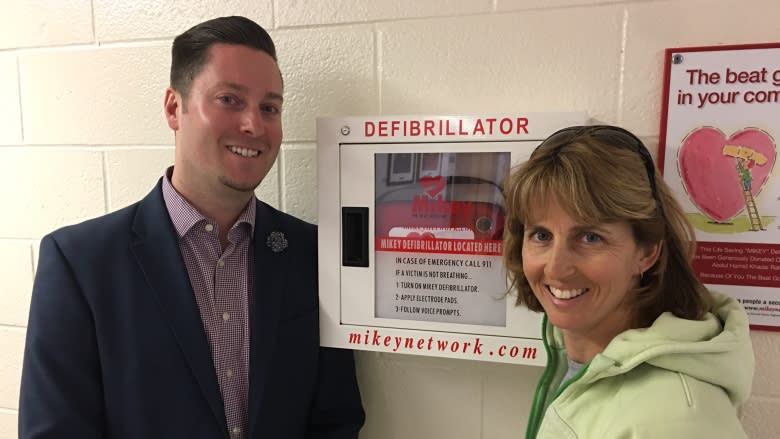

Tom Condotta, a vice principal with the Dufferin-Peel Catholic District School Board, also jumped in to help that night at Chinguacousy. He was playing in the recreational volleyball league that takes over the school on Thursday nights, when a woman ran in and said a man had suffered a seizure.

"There were a lot of people in the gym, people were shouting a lot of different things, it was very confusing," Condotta told CBC Toronto.

Like Fournier, he has CPR and first-aid training because of his position at the school board. He turned the man over from his stomach to his side and directed someone to check his bag for medication.

"It looked like he was kind of snoring," Condotta said. "I asked for someone to go and get a defibrillator."

As he performed compressions Fournier set up the defibrillator.

"I wouldn't say there's a tremendous sense of confidence going through those motions," Condotta said.

'It seemed to carry on forever'

"There's no one around you telling you, 'You're doing it right.' There are no physical signs coming from the individual that lets you know that what you're doing is good, to keep it up. And it seemed to carry on forever."

While others in the gym thought the man was still breathing, Fournier recognized that the snoring sound was actually agonal respiration, an indication the man's heart had stopped.

Fournier teaches CPR and first aid to her students, and tells the story from 18 years ago, but not to scare her students. She uses that painful experience to explain how much harder it would be to process if she hadn't known what to do to at least try to help.

"So that's what I tell the kids when I'm teaching the course, that you never want to be in a situation where something's going wrong and you just don't know what to do," she told CBC Radio's Here and How earlier Tuesday.

"You want to give yourself the knowledge and empower yourself. It might not be perfect, it likely won't be perfect, but you can do something so at least you have the sense of you did everything you could have."