Women like my mom nicked the glass ceiling. Ruth Bader Ginsburg stood on their shoulders.

Wednesday afternoon, I went to the nursing home to see my mom, Audrey Marans Sternberg, on her 94th birthday. Wednesday evening, I went to the Supreme Court to see Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who died last week at 87 and whose flag-draped coffin was resting on the portico beneath the towering marble columns.

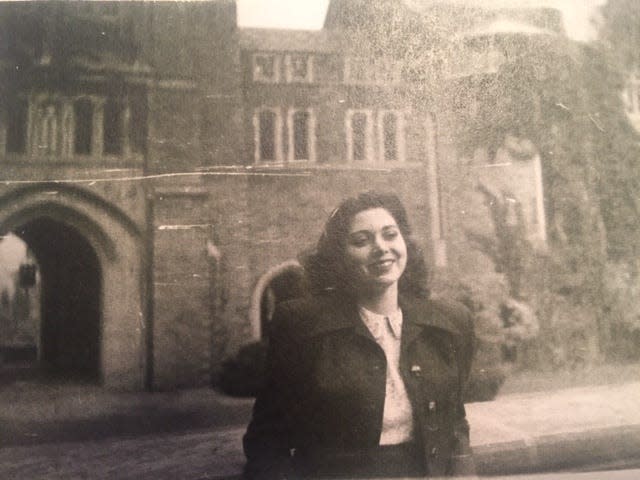

AMS and RBG never crossed paths, so far as I know, but their lives had remarkable convergence. Both were petite Jewish women from Brooklyn, New York. Both graduated from Ivy League law schools when that was a rarity for women. Mom was born on Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year; Ginsburg died on the eve of Rosh Hashanah.

Ginsburg, of course, achieved fame as a pioneer for gender equality and as an improbable late-in-life cultural icon. Mom did no such thing, though I’d like to think she nicked at the glass ceiling in a way that presaged Ginsburg’s later successes.

Beauty, brains, and discrimination

Mom wasn’t on a crusade for women’s liberation. Her reasons for going to college, and then to law school, were more prosaic: “I wanted to get an education so that I could go out and find a job so that, in my spinsterhood, I could make a living for myself,” she wrote in her memoirs.

Justice Ginsburg lived her principles: I clerked for Ruth Bader Ginsburg while raising a young child. She was a model of empathy.

Her mother’s friends weren’t encouraging. They “told her — and me! — that I was getting too much education and no man would want to marry me.” (This concern proved spectacularly unfounded; like Marty Ginsburg, my dad was attracted to a young woman possessing both brains and beauty.)

When Mom entered Cornell Law School in September 1947, there were 126 students in the incoming class, just six of them female. By the end of the first year, the number of women was down to two.

After my mother graduated and passed the bar exam in 1950, she encountered the same obstacles that Ginsburg did a decade later. Private firms in New York weren’t hiring women, so Mom started looking for a job with the federal government. She applied for an opening in the counsel’s office at the Department of the Navy. “You seem very qualified,” the interviewer told her, “but I’ve never hired a lady lawyer and I’m not going to start with you.”

Politics will come soon enough

Among those standing in the hour-long line outside the Supreme Court on Wednesday night, waiting to pay their respects to the nation’s second female justice, were many “lady lawyers” who followed in the trail blazed by Ginsburg.

“I want to honor her in some way and everything she has done for women and women’s rights,” Megan Kiernan, an attorney in Washington, D.C., told me. Her law school class of 250 at Northwestern University, she said, was almost equally divided between men and women.

In fact, as Chief Justice John Roberts noted in his eulogy, women now constitute a majority of the students at American law schools.

The diverse, mask-wearing crowd outside the court on the mild autumn evening was orderly and respectful as it wended its way past floral displays and vendors hawking “Notorious RBG” T-shirts. “There’s no politics here right now,” said Cindy Benedetti of Rockville, Maryland.

Politics will come soon enough, to the Capitol dome across the street from the high court and to the nearby Senate office building where the Judiciary Committee will rush to hold confirmation hearings for the woman President Donald Trump selects to fill the vacancy.

Rethink tenure: Supreme Court term limits do not require a constitutional amendment

In the meantime, at the nursing home 12 miles away in McLean, Virginia, Mom is unable to walk and virtually unable to speak. But she’s still aware of what’s happening.

At the birthday celebration, our daughter — who takes for granted that women have the same educational opportunities as men — told her grandmother via FaceTime that she had just received her Doctor of Psychology degree. My wife displayed an image of the diploma.

Mom’s eyes lit up, and she smiled.

Bill Sternberg is editor of the editorial page. Follow him on Twitter: @bsternbe

You can read diverse opinions from our Board of Contributors and other writers on the Opinion front page, on Twitter @usatodayopinion and in our daily Opinion newsletter. To respond to a column, submit a comment to letters@usatoday.com.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Like Ruth Bader Ginsburg, my mother was a legal trailblazer