Working-class feminist contrarian Caitlin Moran on the joys of mellower middle age

I was born in Manchester, England, and therefore sound nothing like the American stereotype of Brits gleaned from murder mysteries or “Downton Abbey” — upright, uptight speakers of clipped Received Pronunciation. And while American friends find my Mancunian accent nearly indecipherable, in the U.K. it marks not just my regional origins but my class. It’s the first thing that Wolverhampton-born Caitlin Moran picks up on our Zoom call, along with a distinct American twang layered over it. I’m dead chuffed to be speaking with someone from the British working class who has brought that sensibility to her unapologetic feminist writings.

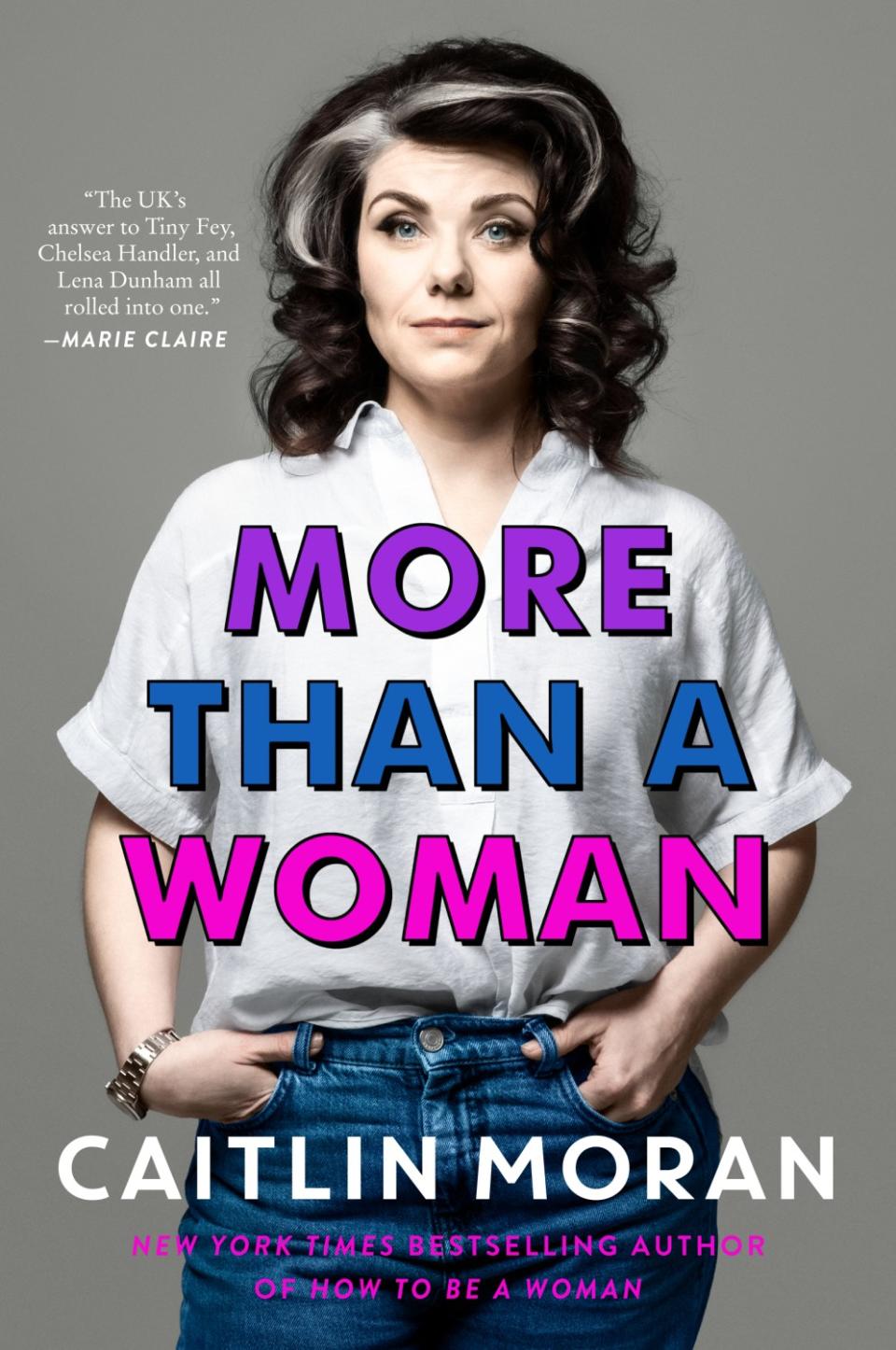

Moran began her career as a teenager, winning a newspaper’s writing competition at 15 and then persuading an editor at Melody Maker to give her her first break a year later. Now at age 45, Moran has made quite some headway; she is about to publish her sixth book, “More Than a Woman.” She also co-created the TV series “Raised by Wolves." Asked in 2013 why she wrote the show, Moran brought up her working-class childhood. “Telly never has any smart, amusing intellectuals living on a council estate,” she said. “That’s why we wrote the sitcom. Well, and the chance to make a load of jokes about vaginas.”

Moran’s irreverent and sweary style was already familiar in the U.K. by the time her first book, “How to Be a Woman,” became a New York Times best seller. One review called Moran’s first novel, “How to Build a Girl,” “a Portnoy’s Complaint for girls.” Not everyone found her style amusing. In 2012 she sparked a feminist firestorm when she bit back at a critic on Twitter and seemed to dismiss the concerns of feminists of color. She clarified her remarks almost immediately — “There is no ‘one voice of feminism.’ … We need whole gangs of girls” — but many thought she had stuck her Doc Marten in her mouth.

Moran herself has copped to a phase during which she wanted “to take the piss out of everything,” essentially the British version of punching up. She had no truck with the notion that “sisters” should support one another without qualification. As she wrote in “How to Be a Woman,” “I don’t build in a 20 percent ‘Genital Similarity Regard Bonus’ if I meet someone else wearing a bra.”

A decade later, “More Than a Woman” celebrates the hard-won wisdom of middle age. The humor is still there, and the anger, but also humility and joy. In her prologue, Moran acknowledges that her observations are those of a “straight, white, working-class woman,” hardly speaking for everyone but instead seeking points of connection.

The book is organized into chapters documenting the hours in a woman’s day — for example “The Hour of Married Sex,” “The Hour of Parenting Teenage Children,” “The Hour of Wanting to Change the World.” Each “hour” becomes an essay on various quotidian challenges.

What infuses the book is joy in the face of mundanity, which she and I get to while discussing the “maintenance shag.” In hilarious detail, Moran chronicles the difficulty for long-married couples of finding time for sex. She and her husband write it into their weekly schedule. She wants to preempt any idea that the chapter is about “women who have gone off sex and husbands still want sex and women gritting their teeth … thinking of England and going along with it.”

No, she means something much more practical and real: the interruptions of work, child-rearing, grocery shopping and such buzz-killing tasks as “swabbing the cat’s stitches and unblocking toilets.” Pandemic lockdown has added a whole new layer of difficulty. One of her most recent encounters with her husband took place as both of their phones dinged multiple message alerts. “Then we finally finished. I went and looked at my phone. There was just the stream of horrified message from my children going, ‘You need better soundproofing.’”

Moran is asking us not to reserve our schedules only for tasks we hate. So it is with feminism. “Schedule in the joy of the feminist movement,” she says. “Watch amazing things and read amazing books and listen to amazing songs that have been made by women.” Activism, she says, should be “50 percent joy and celebration.”

While the book finds many comic moments, there are also chapters on the intense pain of parental helplessness, that moment when a child walks into the kitchen and “appears to be made of rain clouds and sorrow.” In “The Hour of Demons,” she writes of her eldest daughter’s eating disorder. It was her daughter who urged Moran to write about it, in order to make other families feel less alone.

Moran says that when the first signs of an eating disorder appeared, they tried lecturing their daughter on the damage she was doing to her body; then they tried bribery, humor, distraction — all to no avail. Despite the high rate of depression and anxiety among girls, most of us think “it won’t be my family because I am a fabulous parent and I’m doing everything correctly.” But Moran came to see her own complicity. “[T]here was a terrible weakness that I had that was exposed with her. I was scared of her sadness. In my family growing up, we weren’t supposed to be sad. We told a joke and cracked on with it.”

In her first book, Moran occasionally came across as someone who bashed others for their bad taste or conventionality. In our conversation, she tells me that has changed. Dismissing or complaining about others “has no point, and it’s destructive and it’s hurtful and it takes up too much time.”

Her daughter’s situation was a hard lesson in empathy. “It took me two years to realize that I needed to sit with her, to say, ‘I can see you are unhappy. I am not scared of your sadness and I will be with you until this passes,’” says Moran. We talk for a minute about learning as mothers to listen and acknowledge pain, instead of pushing our own perceived wisdom and experience onto them.

The book also focuses on the still-persistent gender disparity in child care and elder care, which was also the conclusion of a United Nations study. Moran says she likes to fantasize about creating a massive women’s union, in which “activists would be paid to represent the interests of women.” And not just white middle-class women. “We ask everyone to give their time to feminism for free and it throws up class and race barriers.”

Instead of being a midlife crisis book, “More Than a Woman” has actually eased Moran’s fears about growing older. She writes: “The fearlessness you have now, in your older years, is the knowledge that, whatever happens, and however hard you inevitably break, you will live through it — one step at a time. And as you become tougher, you simultaneously realize how fragile other people are. You are gentler. You are kinder. You automatically presume everyone you speak to has a secret soreness or sorrow. Because almost always, they do.”

Berry writes for a number of publications and tweets @BerryFLW.