New York public urination debate tests 'broken windows' theory of crime

New York, no longer the crime-infested Gotham it once was, still has little tolerance for anyone with a full bladder and an empty wallet.

In a city where free public restrooms are few and far between, many resort to relieving themselves in public.

"Sure, I've done it. I've done it here," conceded Brooklyn resident Daniel Olivero, on a recent visit to McCarren Park, a hotspot for public urination citations. "When you have to do it, you have to do it."

Although police have never caught Olivero in the act, the consequences could be severe. Public urination remains an arrestable act in New York.

New York is weighing whether to decriminalize urinating in the streets, as many argue that the theory of criminology that gave rise to more aggressive policing on petty violations was built on leaky logic.

"Broken windows is analogous to putting a dirty Band-Aid on a flesh wound, without dealing with the root causes," says Monifa Bandele, who sits on the steering committee for Communities United for Police Reform.

"When you push someone into the margins of society by repeating arrests for these low-level violations, that can have negative, collateral consequences for the community."

The 'broken windows' model

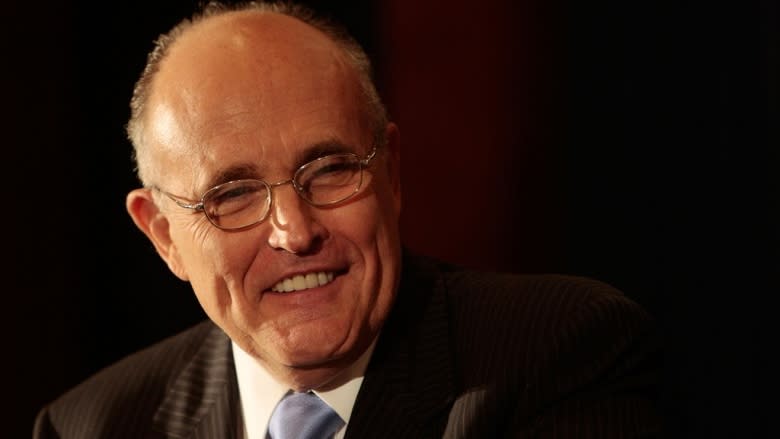

Championed by former New York mayor Rudy Giuliani, the broken windows model is based on the idea that cracking down on minor offences prevents the occurrence of more serious crimes.

These lower-level offences might include urinating in the streets, subway fare-beating, graffiti and unlicensed vending.

Together with New York police commissioner Bill Bratton, Giuliani instituted the broken windows model across the city in the 1990s.

During the mayor's eight-year tenure, violent crime declined by more than 56 per cent, according to the non-profit U.S. National Bureau of Economic Research. Robberies fell by about 67 per cent.

With the tougher enforcement, however, came complaints of unlawful stop-and-frisks and police brutality.

Those who support the cessation of arrests for misdemeanours such as public urination argue that the sweeping enforcement approach of broken windows has lost relevance in a safer, more secure New York.

Under a city proposal, the criminal court summons would instead become civil charges subject to fines.

"Nobody wants their sidewalk or the elevator in their building to smell like urine, but there are 10 other types of strategies to try out instead of having an armed person approach someone and arrest them," says Bandele.

"Yes, public urination is a quality-of-life concern, but what's the solution? Is it maybe more public restrooms? Is it a huge housing crisis?"

Community activists not only believe that policing is the wrong approach, but worry it could have long-term consequences for the offender.

Tickets for such infractions can lead to warrants, Bandele said, which may prevent offenders from being accepted to college, or lead to them being jailed overnight and losing wages, jobs and housing.

Unintended consequences

Critics of broken windows argue that unforgiving policies against low-level violations pushes people into the criminal justice system.

Of particular concern is that it disproportionately targets blacks and Hispanics, and subjects minorities to unlawful stop-and-frisk scenarios.

One example critics point to is the death of Eric Garner, the black man who was allegedly put in a chokehold by an officer who stopped him for selling untaxed cigarettes in Long Island.

Amid the renewed debate, even the originator of the broken windows theory has concerns that it has been misinterpreted or misapplied over the decades.

George Kelling, the criminologist who coined the concept in a 1982 article with the late sociologist James Wilson, stressed that "arrests should be made as a last resort."

Broken windows, he said, is not to be confused with a zero-tolerance approach.

"As we first conceived it, broken windows has always been highly discretionary," Kelling said. "It's good we're having a public debate about it, and we should be reconsidering how we tackle problems that are different than the problems we had in the '80s and the '90s."

As innocuous as public urination or the sale of loose cigarettes would seem to be, Kelling stopped short of recommending that New York decriminalize low-level offences.

"We don't want to lose the capacity to deal with people who are literally saying they can piss anywhere they want," he said.

'No significant effect' on major crimes

Complicating matters is research that suggests there's little evidence the plummeting crime rate during Giuliani's reign should be credited solely to broken windows.

George Mason University criminology professor David Weisburd says the best mechanism might not necessarily be arrests or stops, but simply deterrence or an increase in police operating in "sentinel roles" or patrolling certain neighbourhoods.

Economist Hope Corman, who teaches at New York's Rider University and co-authored an analysis of the effect of misdemeanor arrests on felony crimes in the 1990s, said the arrests "had no significant effect on murder, burglaries, assaults or rapes."

She noted that due to a stronger economy, the 1990s saw increases in the size of the police force of about 35 per cent from staffing lows in the 1980s.

The "decline in crack cocaine use, better policing, increased imprisonment and demographic shifts" may have also affected New York's crime stats, she added.

Current Mayor Bill De Blasio promised to reform the stop-and-frisk program, which was ruled unconstitutional in 2013.

In the first quarter of this year, police stops have dropped to 7,000, or half the amount in the same period last year, although an auditor said some stops may have been underreported.

To Olivero, sitting in McCarren Park, broken windows will always be the policy that straightened up his city.

"Before Giuliani, it wasn't very nice," he said. "Giuliani cleaned it up."

Nevertheless, Olivero supports decriminalizing minor infractions such as public urination.

"People are going to jail now for any little nonsense, and that's not fair," he said. "Their argument is you take care of the small crimes, you'll take care of the big crimes. But how do we know that's true all the time?"