Young Ontarians struggling with income and housing, and it's not 'bad luck'

A new report out from Vancouver-based campaign Generation Squeeze says Ontario has the second-worst economy for young people in the country, eclipsed only by British Columbia.

"No province reports a decline in full-time earnings [for the typical 25-34 year old] since 2003 except Ontario. That wouldn't be so bad if Ontarians' primary cost of living — housing — was also not going up in price," said the lobby group's founder and University of British Columbia professor Paul Kershaw.

The report, part of the Generation Squeeze's Code Red campaign, suggests that a housing affordability crisis in Ontario is affecting quality of life and causing young people to put off important milestones, said Kershaw.

"They delay starting their own homes, moving out of their parents' homes, and starting their own families," he said. "This is compromising a range of family formation aspirations people have."

The report's data, gathered largely from Statistics Canada, explains the financial reasons behind that delay: the average house in Ontario has increased in cost by more than $300,000 after inflation since the late 70s and early 80s.

Meanwhile, full-time earnings have fallen by $4,600 in that same time frame, putting Ontario's young people below the national average when it comes to income for full-time work.

Working full time and watching money 'down to the penny'

The effect of stagnant income is a daily reality for Victoria Mininni, 24.

Despite working full time as a designer, she also works as a bartender on the side. It's part of the shell game of trying to save money for emergencies while covering rent, bills and paying off student debt.

Mininni had tried to get by on her design job alone, but found she had to watch her money "down to the penny." Now, she works upwards of 60 hours a week, leaving her with limited time to see friends and take care of herself.

"I'm pretty accustomed" to having two jobs, she told CBC Toronto. "It takes a lot of time management."

And the possibility of getting into the housing market? Yeah, it's not even on her radar.

"I try to save, but it's really difficult," she said. "I don't know when I'll be able to stop living this way."

'There might be a sense that they've done something wrong'

Emily Paradis, a housing advocate and senior research associate at the University of Toronto, said young people like Mininni might have the mistaken impression that "it's their fault" that their financial stars won't align.

"There might be a sense that they've done something wrong," the researcher said. "But this isn't an individual issue, it's not a matter of individual good or bad luck: it's structural."

Kershaw agrees, arguing that the only way forward is to change a structure that's keeping housing costs out of sync with income.

Generation Squeeze's report suggests that Ontario should "build the supply of homes that will keep home prices in reach for young adults." The province also needs to increase density in residential communities and create policy that will lower the skyrocketing costs of child care, the report found.

Finally, the report also advocates for the end of the so-called "1991 loophole" a policy that abolishes annual rent increase caps for buildings built after November 1991.

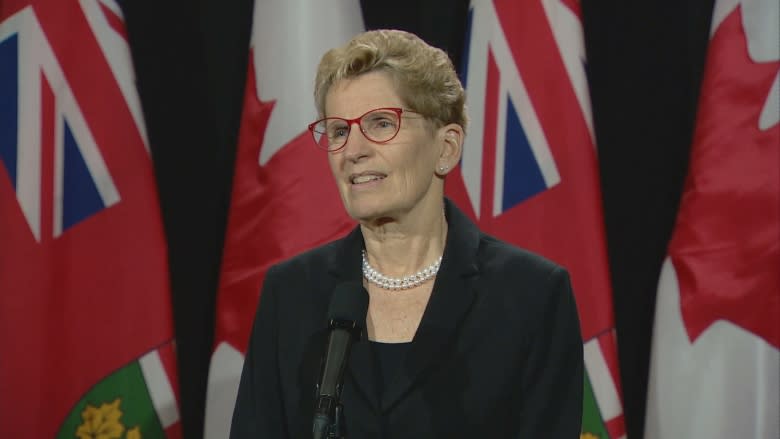

Generation Squeeze has been circulating a petition related to the loophole directed at Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne. She may have already taken note — she said on Tuesday that her government is planning "substantive" rent control reform.