25 years after they came back to Ontario, expert says elk population still not stable

A quarter century after elk were brought back to Ontario, there are concerns they could once again vanish from the landscape.

The latest provincial surveys show the herds haven't grown much since the original 440 were trucked in from Alberta between 1998 and 2001.

"For me it was a personal thing," said Josef Hamr, a wildlife biologist who was one of the leads on the elk restoration project.

"I was really hoping we could re-establish a viable self-sustaining population. It was kind of the goal of my professional career and to see it peter out is pretty sad."

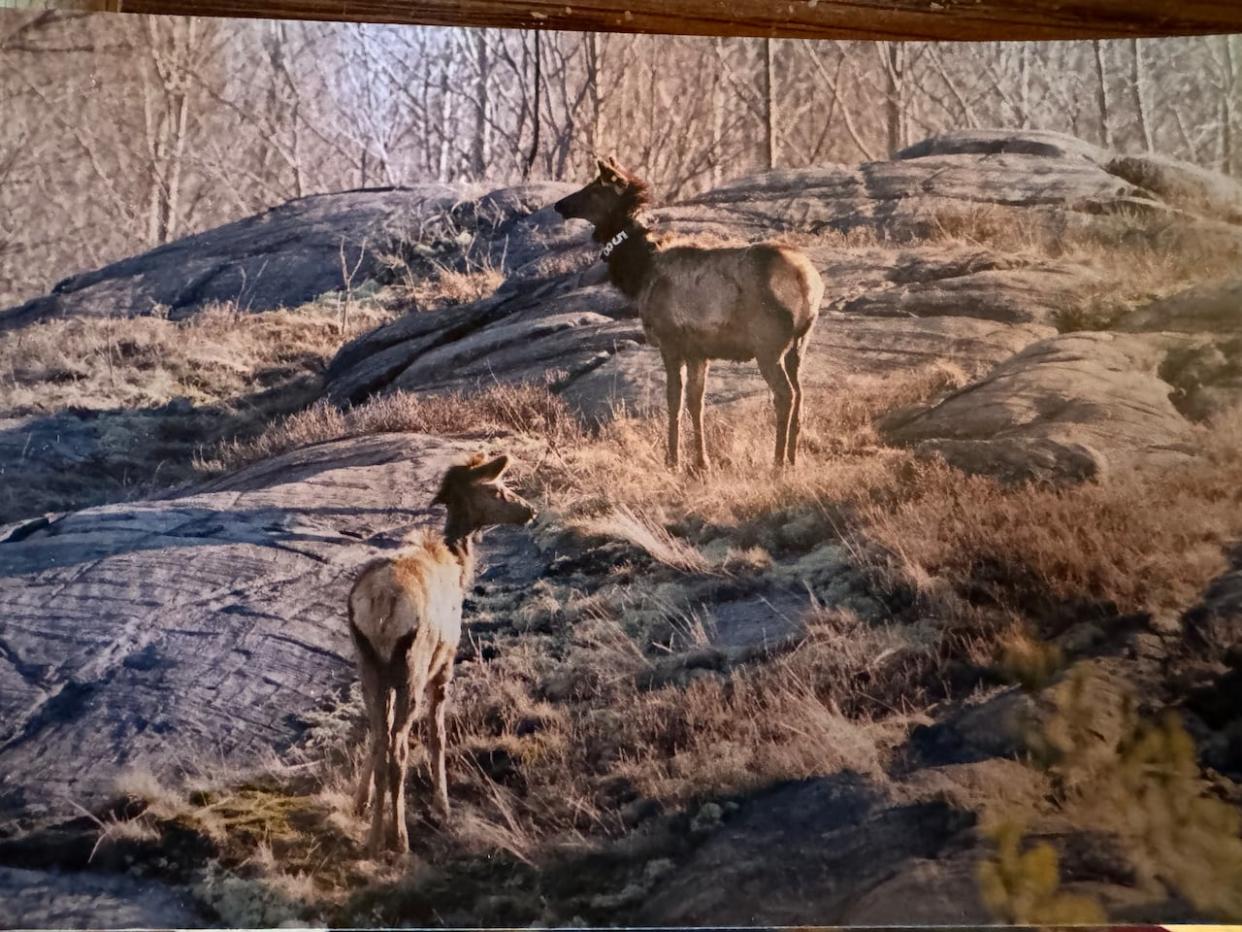

Elk brought from Alberta at a cost of $2 million were released from enclosures into the Ontario wilderness, establishing herds near Bancroft, the Lake of the Woods, Burwash and the north shore of Lake Huron. (Supplied/Joe Hamr )

There is some debate, but there are reports of elk being seen in Ontario in centuries past, before being wiped out by overhunting in the late 1800s.

In the 1920s, the Ontario government decided to bring elk in from Alberta, placing them in several locations across the province, including in Algonquin Park and in the Burwash area, south of Sudbury, where they were in the same enclosure as some bison, which the province was also looking to add to its roster of wildlife.

Hamr says most of the elk were slaughtered when the giant liver fluke parasite was found in the herd, but some in the Burwash area survived.

Biologists studied the descendents of those animals in the mid-1990s, and collared 15 of them. That included Hamr, who then got "excited" about the idea of fully restoring elk to Ontario.

"It's a sexy animal," said Hamr, now retired from teaching at Cambrian College and Laurentian University in Sudbury.

"It's large and it's majestic and for a wildlife biologist to get a chance to work with it was a unique opportunity."

Livestock trailers of elk from a national park in Alberta were trucked across the country, with 170 landing in Burwash, 120 on the north shore of Lake Huron, 200 in the Bancroft area in southern Ontario and a smaller herd near Lake of the Woods in the northwest.

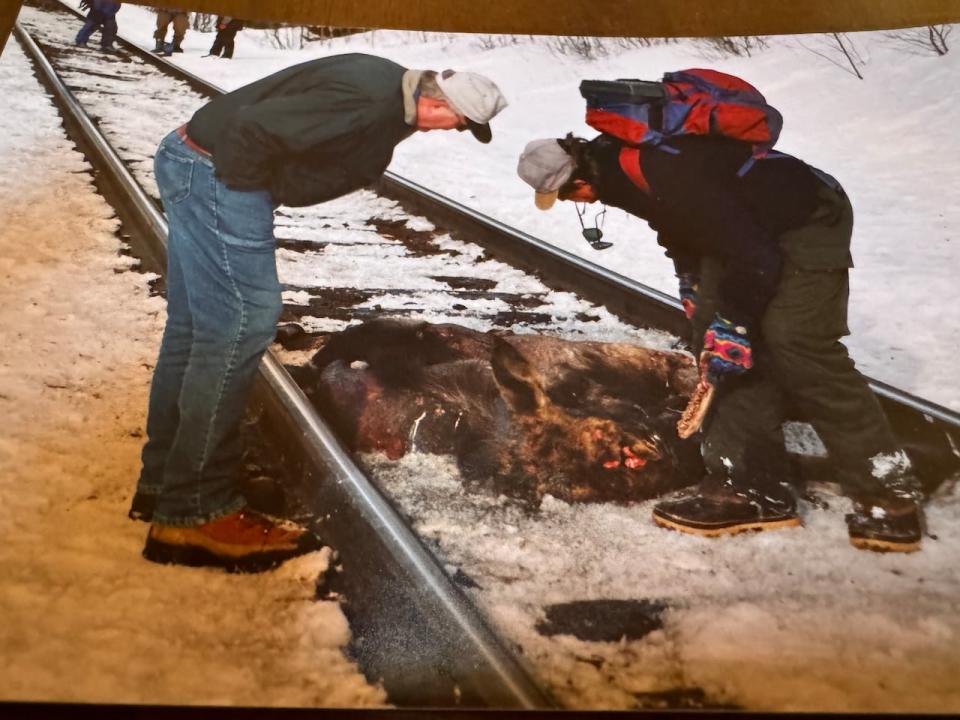

Biologist Joe Hamr (left) is worried that the elk herd has been thinned out by Indigenous hunting, but also high rates of the 'naive' animals getting hit by cars and trains. (Supplied/Joe Hamr)

Lots of elk have died in the years since, hit by cars, hit by trains, eaten by wolves and shot by Indigenous hunters.

The elk have become a major nuisance for farmers along the north shore and while they are not allowed to shoot the protected species, many have welcomed First Nations hunters onto their land instead.

"They're not deterred by fences. They just break posts, tangle up fences, pull down electric fences. The damage can be quite severe. It's very frustrating," said Thessalon area farmer Peter Woolcott.

"I'm sure farmers have tried just about everything."

Retired wildlife biologist and confessed 'elk-aholic' Joe Hamr says the Ontario government could do more to ensure the elk population remains stable. (Erik White/CBC)

"You know if every farmer along the north shore invites First Nations to shoot elk, pretty soon there won't be any left," Hamr said.

"A lot of time and money went into the project and it's a shame to see it go down the drain."

Hamr says recent aerial surveys by the Ministry of Natural Resources showed about 100 elk in each herd, which he says it not enough for the population to become self-sustaining.

He says there had been hope that the provincial government would bar anyone from hunting elk, including Indigenous people, but that protection was never put in place.

Anishinabek Nation Grand Chief Reg Niganobe says First Nations should have been consulted before the elk came back.

"A lot of this stuff could have been dealt with at that point, but they didn't feel a need to consult with the First Nations. And here we are now," he said.

However, Hamr says area First Nations were consulted before the elk arrived and some communities even contributed financially to the project.

Scientists spotted elk in the Burwash area south of Sudbury in the mid-1990s, who had been part of a reintroduction effort from the 1930s, inspiring them to try to bring more elk to Ontario from Alberta. (Supplied/Joe Hamr)

Woolcott says farmers have brought their concerns about elk and wild turkey—which have also caused a lot of crop damage since they were reintroduced to the area— to the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, but "it's like talking to a blank wall, basically."

He'd like to see the province compensate farmers for crops lost to wild animals, like there already is for livestock losses, and thinks the money could come out of the hunting license revenue the province collects.

"Farmers and outdoor recreationists are natural allies," said Matthew Robbins, a fish and wildlife biologist at the Ontario Federation of Anglers and Hunters.

"We all want what's best for the landscape. And we all lose if we start to point fingers too much."

Hamr says farmers, hunters and elk have co-existed in Alberta for decades and is confident a balance could also be found in Ontario.

He'd also like to see the province take a more active role in managing the elk population, following the lead of neighbouring Michigan, where the government even plants food for elk in the bush.

"The management there is quite rigorous, here, you really have to twist arms to do a survey to find out how many are left," Hamr said.

The elk on Mike Soenens's farm in the Chelmsford area of Greater Sudbury are tested for chronic wasting disease when they are slaughtered and have never come back positive. (Erik White/CBC )

The other option for bolstering Ontario's elk would be to transplant animals for a third time, but that seems unlikely in a time of high concern over chronic wasting disease or CWD.

The deadly condition has been found in Manitoba, Quebec and all five U.S. states that border Ontario.

Mike Soenens has been an elk and deer farmer in the Chelsmford area of Greater Sudbury for 32 years and says every animal has to be tested when it's slaughtered.

"I can see where they might have a concern, but we've proven over 20 years that we don't have CWD on farms," he said, adding that he doesn't see the same focus on the wild population of elk, deer, moose and other cervids.

"The risk right now, if it was introduced in the wild, it will destroy all cervids in the wild and it's really hard to stop once its here."

Mike Soenens says regulations on his elk farm have tightened over the years, while it seems the provincial government isn't as worried about chronic wasting disease in wild elk. (Erik White/CBC )

The Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources provided a statement listing all the measures it has in place to stop the spread of chronic wasting disease.

The ministry also noted that it is continuing to monitor the elk population, following its elk management plan and works with farmers and other land owners to minimize conflicts with wild animals.