After 6 suspected overdoses, Toronto councillors want amnesty for users who test drugs

Six suspected overdoses, one fatal, in Toronto's club scene have prompted a municipal councillor and harm-reduction advocates to push for Health Canada's approval in offering amnesty to those who want to test drugs before ingesting them.

The city's board of health approved the measure as part of its drug strategy in March.

That recommendation will see the municipality work with hospital testing labs to develop a program so that users can test the substances they buy.

At the moment, it remains a murky legal issue.

How to save lives

But Coun. Joe Cressy said that harm-reduction and prevention strategies are as critical, if not more so, than enforcement — especially when it comes to reducing the number of fatal overdoses.

"People use drugs," he said. "So telling people not to use drugs doesn't work; in fact, it leads to more deaths unnecessarily. But if people know what's in those drugs we can help to prevent the unnecessary loss of life."

A 24-year-old woman died of a suspected overdose early Saturday morning after she collapsed at Uniun nightclub. Another woman at the same club was also taken to hospital in serious condition, while three others at Rebel nightclub on Polson Pier are believed to have suffered overdoses on the same night.

Toronto Police Services issued an alert in the wee hours of Saturday morning warning users of a "bad batch" of MDMA, also known as ecstasy.

The toxicology reports have not yet been released to the public. Police have not provided any indication as to whether there's a connection between the incidents, except for a spokesman this weekend who described the cluster of overdoses as unusual.

Public health approach is 'better way'

Cressy said the city has been pushing for Health Canada's approval for this and for supervised injection sites and it "needs to happen yesterday."

Toronto saw a 73-per cent increase between 2004 and 2015, with many of those being linked to powerful opioids like fentanyl. In 2015, 135 opioid users died after overdosing, according to figures from Toronto Public Health.

"A criminal justice approach is a failed approach for drug policy," Cressy said. "A public health approach is a better way to go."

Critics of publicly offering testing, however, have historically said that it encourages drug use and encouraged more enforcement.

But the director of the Ontario HIV and Substance Use Training Program said that argument is akin to those who disapproved in the 80s when public agencies began offering condoms to prevent the transmission of HIV-AIDS.

"It's not like we're going to shopping malls and encouraging drug use," Nick Boyce said. "This is for people who are already using it. It's a tool that can help people be safe."

Boyce's approval, however, came with the caveat that such testing kits are not completely accurate. And he noted that using carries with it a set of risks and that people overdose for reasons other than tainted drugs.

Success in B.C.

Cressy said that the board of health would be looking at offering the testing at the three supervised injection sites and, potentially, at some music venues. The latter was a model that's been used at British Columbia's Shambhala Festival.

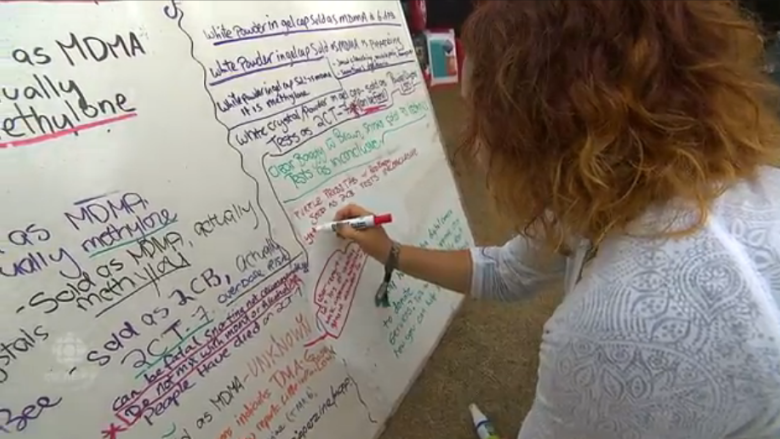

Lori Kufner attended that festival and said there was always an "hours-long" lineup, which indicated it was a valuable service. The results of the testing would be posted on a board outside the tent so that others would know if any drugs had been laced with other substances.

Kufner, the co-ordinator of the Trip Project, a publicly-funded initiative which provides harm-reduction information to drug users, said she understands that nightclubs are in a difficult legal position.

"But it's going to keep happening no matter how much they do to create a no-tolerance policy around drug use," she said.

The Trip Project, which began in 1995, offers outreach booths that can be set up at events. The booths, staffed by a handful of volunteers, offer safer drug use and safer sex information and supplies.

"We at the Trip project can do outreach at parties and events and talk to the patrons about prevention strategies," Kufner told Metro Morning on Tuesday.

"We have a little booth set up and some really great peer workers who can chat with partiers on the spot and talk about different risks, talk about what not to mix together, and how to spot an overdose among their friends who are using.

"Nobody wants to have an overdose."