What 8 hours a day on TikTok taught her about the ultra-rich and influencer culture

Looking back, the early pandemic period seems almost like a fever dream.

In the first half of 2020, we hunkered down in our homes. The outside world brimmed with a perilous danger we didn’t quite understand, so we spent our days connecting with friends and family over screens.

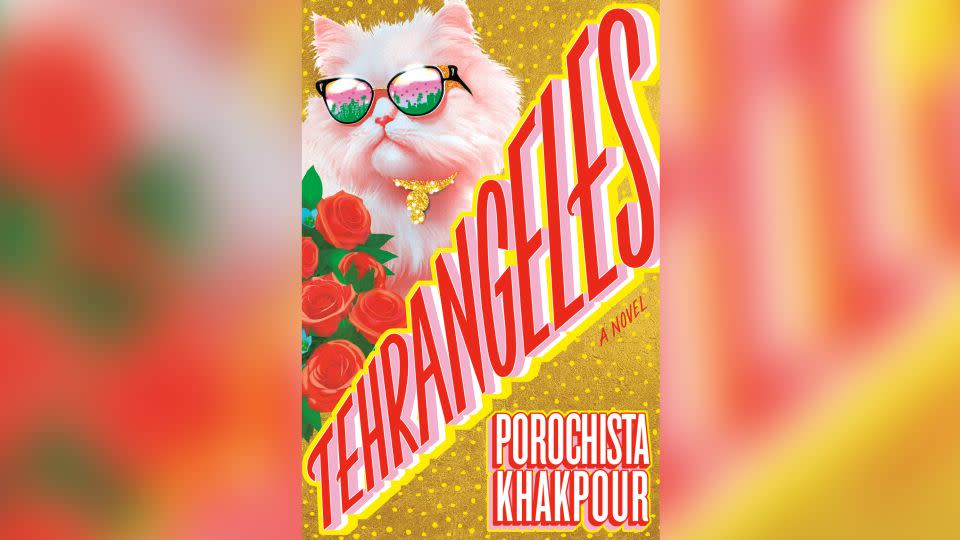

For writer Porochista Khakpour, the period presented an ideal parameter for a plot. And thus it’s the setting of her latest novel “Tehrangeles,” a portmanteau of Tehran and Los Angeles, named for the large Iranian community in the US city.

The book, released last week, revolves around the Milanis, an ultra-rich Iranian family — think Bravo’s “Shahs of Sunset” — on the verge of launching their own reality TV show.

Shifting through the perspectives of each character in the family, “Tehrangeles” unveils the threads of the family’s dynamics, weaving together a collage of secrets and mishaps, with the internet as a driving force. Case in point: In one scene, TikTok dancer Addison Rae, whose popularity soared in early 2020, makes an appearance at a party hosted by the Milanis.

“I felt really compelled to sort of freeze this moment, to really take a close look at this exact moment without thinking far in the future,” Khakpour told CNN, speaking of internet culture in the early pandemic era. “I wasn’t seeing it enough in books around me, so I really wanted to do it with, of course, an Iranian American twist, because those are my people, and I was seeing them trying to take part in this just as eagerly.”

The end result is a satirical look at how celebrity, wealth and social media operate together, especially against the backdrop of a super rich Iranian community in Los Angeles. Similar to our fascination with real-life reality stars (from the Kardashians to former president Donald Trump), we can’t seem to look away from the Milanis and their obsessive pursuit of status.

CNN spoke with Khakpour about early pandemic influencers, Iranian American assimilation and spending eight hours a day on TikTok for research on the book.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What made you choose to set “Tehrangeles” during the early stages of the pandemic as opposed to pretending it doesn’t exist?

For me, it’s actually a period piece. The pandemic was absolutely personally devastating. I mean, I lost seven friends. I was in Queens (New York), at the heart of it, it was a horrific experience, and I have chronic illness issues. But I was really wanting to write a satire around the mishaps around the pandemic. For instance, the influencers throwing super spreader parties. I was watching that with absolute horror on TikTok every day, just thinking, “What is going on? How is this real?”

I started this book in 2011 and I really didn’t know what the setting was going to be. I had the characters set. I had the basic scenario set with reality TV, the potential of war with Iran, aspects like that. But I really had no idea about when, in time, it was going to take place. And so I was constantly redrafting it, revisiting aspects of the plot. And then when the pandemic hit, I was like, “Oh, wait a sec, this is the setting.” You have the ultimate restriction, a bunch of people who are confined to their homes. It just was, to me, an ideal conceit for a novel, because you can really turn up the heat and get things to a boiling point where family dynamics are concerned.

What were you trying to say here about the ultra rich?

Well, I’ve always been an outsider to this class, the upper class. But I’ve definitely been an observer. I’ve had some relatives that have punctured this class here. I’ve been a shop girl on Rodeo Drive. When we grew up in the San Gabriel Valley part of LA, we would drive out the 40 minutes or so to the Tehrangeles neighborhood (Westwood), and I would be in contact with these extremely wealthy Iranian Americans all the time. So I really got a good look at them.

And then, of course, on the total flip side, watching the world of reality TV or the world of TikTok and influencers and all that. Again, I’ve been an observer. I’ve never really been a part of that. In fact, I don’t share an age with any character in this book. So I’m a complete outsider to this. But I often think it’s the outsiders who have a really good lens at stories like this.

So it was very important for me to convey that this is definitely satire. The challenge, though, was how to write satire that still has some heart, because it’s very easy for me to poke fun at the rich. I can do that all day. I don’t believe in billionaires. I think there should be none, so I have very different politics than most of my cast. It’s very easy for me to just be very disdainful of these types of people, but really it was the other end of it that became the real challenge. How do you then make this a more worthwhile ride for the reader, where they actually have moments of empathy with these characters?

You mentioned it took you over a decade to write this book. Do you think that your own changes over the course of the decade influenced your characters and the world you were creating?

Actually, the characters didn’t change too much, but how I wrote them changed. There was a long period where the central protagonist, Roxanna, was so reprehensible to me. I just dreaded writing her sections. I found her so irritating. I found her just to be unacceptable in every area. And I had to figure out, “How do I find a way to feel for her, even though she would have been the girl in high school that bullied me?”

It’s more like what was going on in the world that helped shift things for me. I mean, the central anxiety for me originally was war with Iran. It’s interesting how that comes and goes in news cycles. Like in January of 2020, a lot of us Iranians were pretty convinced the US was going to go to war with Iran after Soleimani’s assassination. We were very prepared for that.

And then, recently, with what’s been going on in Gaza, again, I’m like, “Huh, looks like the US really wants, sometimes, war with Iran.” So we go back and forth with this. The political climate, the socioeconomic climate, of the US actually swayed me.

Also, TikTok really affected how I saw the book and the characters, too. I was on TikTok very, very early on, just lurking. And that was the only way I had access to Gen Z creators with tens of thousands, some hundreds of thousands, some millions of followers, and I got a real sense of how they lived and how they saw the world.

Some of them were, I thought, pretty smart. They’re pretty interesting. They’re pretty good people. But some of them, just the prospect of getting rich and monetizing their every thought — everything from a little dance move to like a funny quip — the way that every aspect of their being could be monetized, watching that transform these young people was really fascinating to me. It horrified me on one level, but on another level, I wanted to know how the story would end. What are these young people going to be like when they hit middle age like me? I don’t really know. I hope they’ll be okay.

Some of the characters that show up in the book are so indicative of that specific time, and I’m not even sure if we have even had time to go back and think about it and process it.

So much has changed. During the fact-checking process, it was so funny, like Kim Kardashian was Kim Kardashian West in this book; we had to look back to make sure. There’s an emoji we use at a certain point — did it exist, as we put it, in 2020? I mean, it was wild, the process we had when we were going through it all, the type of research we had to do to make sure it was a proper period piece. Because already, the trends on TikTok are completely different.

When I see the words “hype house” — that was all over my notes very much when I was writing this book — I don’t think anyone’s going to remember what I’m even talking about.

I had to really get to a point where I was consuming this stuff like someone in their teens and early 20s. I spent a lot of time, sometimes eight-hour days, on TikTok. And I do have an interest in pop culture. I was a music journalist for a while. I did a lot of entertainment journalism. So it’s not totally outside of my area of interest, but I felt my age. But maybe that was part of why I could do it, because I had a healthy distance.

I can definitely understand that. In a piece for the Los Angeles Times ahead of this book’s release, you wrote, “I never had to go far to find Iran. I did, however, have to go far to find Iranian America.” What is Iranian America versus Iran?

I think the problem with Iranian American cultural representation is that it’s focused on a certain type of Iranian and we saw that very clearly with “Shahs of Sunset.” But even before that, in “Clueless,” when they talk about the Persian mafia and that. I’ve seen all sorts of comedy shows and sketches where they want to have an Iranian character, and it’s really one of two things — it’s either some rich Beverly Hills guy in a white BMW, slicked back hair and tacky designer clothes, or it’s just a straight-up terrorist.

The terrorist one, I feel like we got somewhere with pushing back on to some degree, although, obviously for us Muslims, Islamophobia is a constant. It comes back every few years, of course. But the other thing, this affluent Iranian that has made it — and Americans get a kick out of that caricature — it’s become a sort of acceptable caricature, even within Iranian communities at times, because they see that as someone that’s non-threatening, that can still get good jobs, still make money.

But the reality is, there’s tons of Iranian Americans, like my family. Lots of us don’t fit into that picture at all. And actually we are really the majority. Some might argue and say, “Look, Tehrangeles, that’s the biggest population of Iranians outside of Iran.” But they’re not all 90210 Iranians. I lived in the greater Los Angeles area. Would I be included in that?

Visibility has been a big problem for us, and at times, I’ve argued for no visibility. I’ve hoped that we could be kind of invisible, because the minute in America there’s a spotlight on a culture, it’s a matter of time before recognition turns into hate. So I’ve been very nervous about that for years.

Iranian America, like any diaspora, is huge, it’s diverse. But because these very affluent Iranians get the most visibility, there’s maybe an attempt to assimilate into Iranian America, versus just trying to be Iranian in America. Is that it?

That’s a really great way to put it. When I came to the US, and I was in ESL classes, fresh from Iran, I heard all sorts of things. People call me FOB (fresh off the boat), all sorts of awful things in that era. But at the same time, it made sense to me. I was a foreigner here. I was learning English. My family ate very different food. I had a different first language. I had a different culture. We had different celebrations. It all made sense.

But what really created that cognitive dissonance for me was then seeing other Iranians who were way ahead of us in assimilation, who were desperate for assimilation in a way that we really weren’t. It was almost that uncanny feeling when you see something that kind of looks like you, but completely acts different. It’s adjacent, but off. It wasn’t a mirror image. I was really surprised by it. And I’ve never really found a community in the more conservative Tehrangeles wealthy Iranians; I think that goes for a lot of us.

A lot of Iranians are also ashamed to admit that their communities would reject them. So the shame, combined with just these major cultural gaps that have to do with class, as well as ethics and all sorts of things, it just creates a really weird type of alienation that really hasn’t gotten better for me as I’ve gotten older. I’ve just found a place for myself as a writer and observer of all that. But creating community has always been hard for me as an Iranian American. Every time I go to these readings, I meet Iranian Americans and I’m so excited. I’m like, “let’s keep in touch!” because it’s always hard to find us, even though the numbers tell a different story. We are here.

A friend of mine jokes there’s a lot of stealth Iranians. They don’t want to fit in with the Tehrangeles set. They’re so afraid of being filed under those, whereas it used to be a fear of being filed under the terrorists. So now they just become stealth Iranians, and they’re just hoping that people will only see them as maybe Muslim or Jewish or just an artist or queer or whatever it is, because it’s gotten so confusing.

Right. Like with your book, you’re holding up a mirror to the Tehrangeles Iranian American side, but then there’s all these other Iranian Americans that exist, living their life, maybe in contrast to the Tehrangeles Iranian America.

Yeah. The boy in my first novel, “Sons and Other Flammable Objects,” grew up in an apartment district like the one I grew up in in the San Gabriel Valley. That guy has no intersection with these young women in Tehrangeles. They will probably never meet in their life, and they probably won’t really know they even exist. And yet, they are technically in the same city. They technically have a lot in common, actually.

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com