An Ancient Portal to the Underworld Was Found in Denver

Originally stolen sometime in the early 20th century, a “portal to the underworld” depicting the Olmec jaguar god Tepeyollotlicuhti returned to its Mexican home in May of 2023.

Because the looters broke the object into smaller pieces, Mexican authorities with the government’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) have spent a year restoring the statue to its former glory.

The return of the statue was the result of a decades-long effort among archeologists and officials working in stolen antiquities.

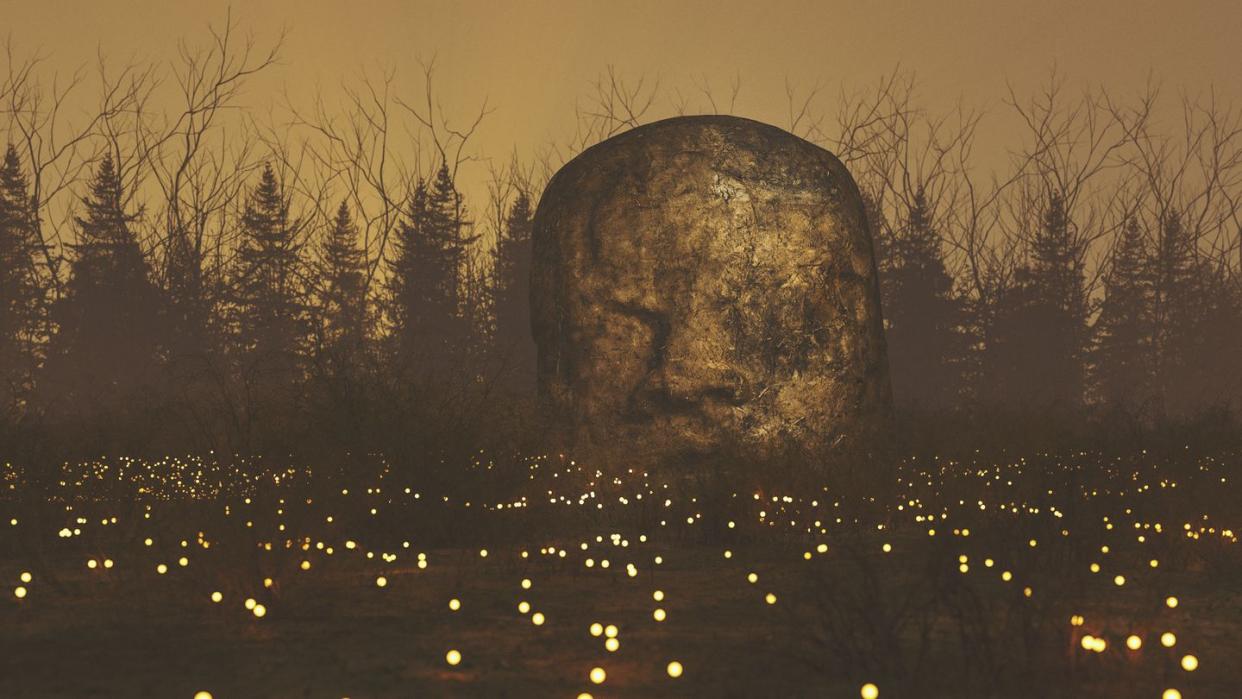

Sometime in the early 20th century (officials aren’t sure exactly when), looters made off with a 2,700-year-old treasure of the Mexican-based Olmecs—one of North America’s first major civilizations. The artifact was a six-foot-by-five-foot Olmec Cave Mask, also known as a Portal al Inframundo (“passage to the underworld”), depicting the Olmec jaguar god Tepeyollotlicuhti with its flaring eyes and gaping mouth.

Originally located in Chalcatzingo in the Mexican state of Morelos—an area famous for its Olmec artwork and iconography—the looted statue went on a decades-long journey, winding in and out of different museums and private collections in the United States. Eventually, this ancient hell gate wound up in Denver in 2023 and, finally, authorities from the Antiquities Trafficking Unit based in New York City secured the masterpiece. Within a couple months, the long-missing statue made a return trip to Mexico.

“This incredible, ancient piece is a rare window into the past of Olmec society,” New York District Attorney Alvin Bragg said in a press statement at the time. “Like many other looted antiquities, the Olmec Cave Mask was broken into several different pieces to make the smuggling process simpler.”

The National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH), a group within Mexico’s Ministry of Culture (which has been leading the restoration), says the statue was actually broken into 25 pieces. As a result, experts have been working on the piece in situ to “provide greater stability and coherent visual reading,” according to a recent press release.

“Some elements that make it up are original, but others, such as a metal structure based on bolts, cement reinforcements and replacements of missing parts and shapes, were added to give it stability again, even though the techniques and materials were not the most appropriate,” INAH’s Castro Barrera said in a statement translated into English.

Some of those structural elements will likely remain in place going forward.

Amazingly, this cultural wonder would’ve likely never returned to its native soil without the tireless effort of archaeologist David Grove, who was the first to link the Olmec artifact to the one missing from Chalcatzingo. INAH’s Mario Córdova Tello eventually proved that the artifact was indeed stolen, and even pinpointed its location in Colorado, in the hands of a private collector in 2008. Tragically, Grove—who was so instrumental in the object’s repatriation—died the day before the statue arrived in Mexico.

Unfortunately, the Tepeyollotlicuhti portal is only one example of the many priceless antiquities that have been looted from native lands and now illegally reside—both knowingly and unknowingly—in collections and museums around the world. But as pressure rises for museums to return these prized treasures, maybe they’ll also get a long-awaited trip back home one day.

You Might Also Like