Anthony Hopkins on “One Life”'s inspiring story, his regrets, and finding a new audience on TikTok

The two-time Oscar-winner plays Nicholas Winton, who helped saved hundreds of children from Nazi forces before the start of WWII.

Think of Anthony Hopkins' greatest performances — there are many, of course — and a certain serial killer might come to mind. But in his new film, One Life, the two-time Oscar-winner's character couldn't be further from Hannibal Lecter.

The movie, in theaters Friday, tells the true story of Nicholas "Nicky" Winton who, in 1938 as a 29-year-old (Johnny Flynn), helped save hundreds of mostly Jewish children on the eve of World War II, secretly transporting them from Prague to his native Britain before Nazi forces invaded Czechoslovakia. Fifty years later, the BBC series That's Life surprised Winton (Hopkins), reuniting him on-air with one of those now-grown children, and then again with an audience full of survivors and their children. For decades he had kept the missions that he and several others carried out private. Suddenly, though, he was a reluctant hero: The episodes made worldwide headlines — and went viral online years later. But Hopkins admits he wasn't aware of the story when it broke.

"I was somewhere else... I'm not a big viewer of television, so I must have missed it," Hopkins tells Entertainment Weekly over a recent Zoom call from London. In fact, the first time he heard about Winton was from his daughter, who told Hopkins she wanted him to play her father. That was three years ago, at which time Hopkins says he couldn't make the film. But it came back around, with James Hawes (Slow Horses, Black Mirror) attached to direct.

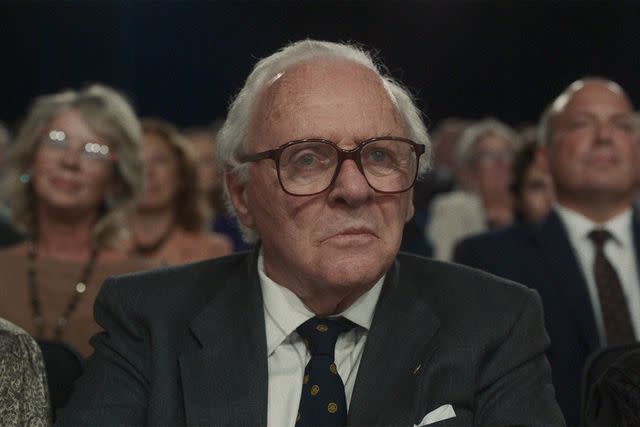

Bleecker Street

Anthony Hopkins in 'One Life'Hopkins remembers being interested in seeing Winton go about his daily life...until his wife discovers a book full of records of the 669 children he saved so many years ago. But with the flashback of those rescued comes the haunting memory of those lost — specifically, several hundred children who were on a train that was about to depart but commandeered by invading Nazi soldiers.

"Neville Chamberlain, our prime minister, declared war against Hitler, and Hitler closed down the borders. And that was the end of that," Hopkins, who was just a year old when Winton's rescues began, explains of the events. "There was that regret [of losing that train of children]. But what he did was make sure that other people had the credit, the people on the 'kindertransport.'...And that's what I admired about him."

Hopkins got a small taste of what Winton experienced that day in the BBC studio when he learned right before Hawes called action on the scene that the audience he was about to join for the recreation of That's Life was comprised of relatives of the children Winton saved — some, Hopkins says, from Switzerland, France, and Romania.

Bleecker Street

Anthony Hopkins and Lena Olin in 'One Life'"They all wanted to be in the movie, so that left me with no tasks at all, no acting required, as they say," he recalls, laughing. "I found it very moving when [host] Esther Rantzen said, 'Anyone here who owes their life to Nicholas Winton, [stand up].' I thought what a tremendous burden that must've been for him... a blessing and a burden of how would you shoulder that responsibility. Do you run away with your ego? He was very generous to the other people who were involved in the kindertransport. He made sure they had the credit, and that was his gift to humanity: his kindness, compassion, and pain, when he lost the last train which vanished."

A conversation with Hopkins reveals a sincere and thoughtful examination of Winton's values and virtues, of upbringing and family. For everything the actor puts into his performance from a psychological perspective, he's just as philosophical about it. "[Winton] was asked by various American journalists after [That's Life,] maybe before he was knighted — I think it was the same journalist from America — 'Do you believe there is a God?' And he said, 'Well, Germany was praying for victory. Britain was praying for victory. America was praying for victory. Russia was playing for victory. So...' And he couldn't answer. [The journalist asked,] 'Do you see any hope for the future?' He said, 'No.' 'No hope for the human race?' 'No, unless we learn to compromise. If we don't compromise and try to understand the other side of the argument — our opposing, so-called enemy argument or opponent's argument — then it's over.' We live in an age of absolutes. I know, and you don't. I'm right, and you are wrong. That's a surprising state to be in after all that happened 80 years ago, and now we're thinking, well, where are we? Have we learned anything? I'm not saying that's a terrible judgment on the human being. We are survivalists and we have to move on. But it's that 'business as usual' that's the chilling part of us."

He mentions Jonathan Glazer's The Zone of Interest, a film he had just watched. "We are selfish, survivalist creatures. We all are," he continues. "To survive, we have to have an ego that pushes it. But when that gets out of line, you'd be skinned to start knowing that you are certain that you can lead 83 million people like the Pied Piper into the abyss as that man did 80 years ago, and then blew his brains out into the rubble of Berlin for an idea. The idea. And that's the terrifying thing, the absolutist idea and the foundation of any dictatorship. And without citing anyone, you hear it constantly on the radio, on the television. 'Let it be understood! Let me be clear!' Politicians say that a lot. Why is everything going down the drain? Why can't people get jobs? But we are all part of the same mechanism. We're only human beings. Once you begin to think you're exalted above that, then it's the end."

While his words are rich with experience, he is quick to dismiss his own wise observations: "But I don't know. I don't know anything."

Bleecker Street

Anthony Hopkins in 'One Life'What he does know is that he's grateful to still be telling stories at 86 years old. "I wake up in the morning and think, thank goodness I'm alive today," he says, admitting that he, like Winton, does think about not just his achievements but his regrets. "You look back, you think, well, that was then. You make the compromise of making amends or apologies, this, that, the other. But finally, you have to move on with life. And if people want to live in their resentment, okay, well that's up to you, but you do the best you can to move forward. As Winton said, 'Save one life, save the world.' Now, that's an easy little simplistic way, but dealing compassionately with people, to be kind — I would say that was my story of my life because I've been a sinner like everyone else. I've done things that I look back and think, how did I do that? But I was young. I had this idea and that idea. And you learn to think, oh, well, that's the way it was then. And hopefully I've learned to don't do that anymore. It's not worth it. Don't do it. Just be kind. Be thoughtful to other people and respect other people. That doesn't mean to say I'm a doormat, but respect other people. Listen, listen, listen. It's easy to fight. It's easy to come out fighting. I was punchy when I was a young kid. I'm too old to do that anymore."

But not too old for social media. The actor has connected with a whole new audience with his posts on Instagram and TikTok, where he has millions of followers.

"My wife and I said, we must have some fun. We must have a laugh," he says, offering up one of his own. "Let's lighten it up a bit because we're all going to be dead one day."

One Life is in theaters Friday. Watch an exclusive clip above.

Want more movie news? Sign up for Entertainment Weekly's free newsletter to get the latest trailers, celebrity interviews, film reviews, and more.

Related content:

Watch Anthony Hopkins channel Sigmund Freud in Freud's Last Session trailer

Tom Felton recalls the 'worst three minutes of improv' with Anthony Hopkins in awkward audition

Read the original article on Entertainment Weekly.