'It gives people a direction, a purpose': Veteran survivors of sexual assault to compete at Invictus Games

MJ Batek stretches in the pool of the local recreation centre in Cochrane, Alta. Her bathing suit and swim cap are emblazoned with the Canadian maple leaf. That tips off the kids enjoying the indoor water park that this local mother of two is someone special.

Batek is suddenly an ambassador for the Invictus Games, explaining all about the multi-sport competition for wounded service members and veterans. The Games run Oct. 20 to 27 in Sydney.

Minutes later, Batek is powering through the breaststroke. Months ago the idea of competing in the Invictus Games wasn't even a thought in her mind.

"I'm not an athlete," she says. "I'm, like, broken … I have days where I have a hard time getting down my stairs, you know?"

Batek suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Unlike many of her fellow veterans and service members, her wounds aren't from combat. Instead, her psychological skin has been scarred by military sexual assault and domestic abuse.

Now she and her friend Donna Riguidel are among a handful of Canadian athletes who will compete at the Invictus Games this month in Sydney with similar injuries: debilitating psychological wounds suffered at the hands of fellow service members. But she likely wouldn't be training for games at all were it not for a serendipitous confluence of events.

It began at a Wounded Warriors retreat in Banff. She had almost backed out of going to the event, afraid of whom she might run into.

"It's completely debilitating terror, like your whole body just starts shaking, and you can't think, you can't talk," she says.

Her sister coaxed her through and into the conference and subsequently into a friendship that would change the lives of two women.

A chat with another woman attending the Banff retreat led to the beginning of a long-distance phone friendship. Eventually their bond became clear.

"We're just having this conversation," Batek says, "and I was like, 'I just kind of want to tell you why I'm here.'"

Talking by phone, she went on to tell the other woman, Riguidel, about a party she attended as a 17-year-old after basic training in Vernon, B.C.

She said the course instructor lured her into the woods to "talk about the course.… He grabbed me and he kissed me and groped me."

She recalled it ended suddenly. "All these lights came into my face, and it was my sergeant and people looking for us. They knew something was wrong."

What could have happened had they not appeared haunts her.

"I mean this is a big man. I will never forget what he looks like. He's in my dreams."

On the other end of the phone, Donna Riguidel sat in stunned silence. The story sounded familiar. At 17, she had also had a frightening experience with her course instructor.

She says her course instructor and another man were bringing her back to an end of course party. She had been escorted home earlier because she was "too drunk."

Riguidel says minutes into their drive, he said, "I want you to give me blow job."

Riguidel tried to talk her way out of it and joke about it. Then, she says, his words turned frightening. "I'm ordering you to give me a blow job."

"And I'm sitting there, and I looked over at the driver and he just sort of glanced and then he went back to the road."

Riguidel managed to bolt to the safety of her friends.

When she and Batek shared his name between them, they made a shocking discovery: their first alleged perpetrator was the same person.

After their experiences, both Riguidel and Batek felt shunned and isolated.

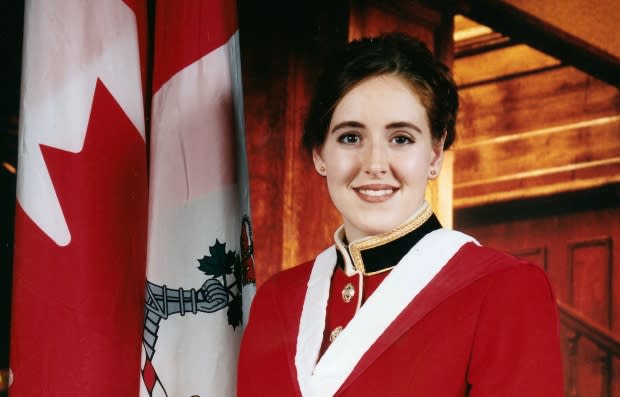

Despite suffering anxiety and low self-esteem, Batek was convinced that going to officer's training at Royal Military College in Kingston, Ont., would change her fate. It was the early 1990s, so she had an opportunity to be one of the first female officers in the artillery.

"There was a real pride, like, you know, I can maybe change this part of the military. I can go overseas, I can make a difference."

Besides, she reasoned that surely the culture among officers would be more respectful to women. That idea was dashed on her first day, when a woman handed her a coat hanger and counselled, "This is how you lock your door. If you don't, a fourth-year will come in here after they've been drinking at the pub and they're going to rape you."

Sexual harassment courses were treated like a joke, she says. By now, she had learned to shut up and take it. "You tolerate the intolerable, and off you go," she says.

Lacking confidence and suffering anxiety, Batek says she entered into a volatile marriage. She was medically released from the military after an injury she suffered during training. At home, she says she was going through verbal and psychological abuse.

It took her nine-year-old son reporting his unstable home life to his school to get the Children's Aid Society involved. Batek left for her children's sake.

Her estranged husband showed up at her home, drunk, depressed and armed with a rifle. Batek thought he was suicidal.

"I could hear the rifle load. I know what a bolt action sounds like. I was like, oh my God, we are going to die."

Thought things would be different

Her now ex-husband pleaded guilty to criminal harassment and unlawful use of a firearm. He is still employed by the Canadian Armed Forces.

Donna Riguidel also left the military. But in 2006, she rejoined as an officer cadet. Like Batek, she thought things would be different on the officer track. Yet another sexual assault incident proved her wrong.

In 2012, then-Capt. Riguidel was on exercise with embedded journalists at CFB Shilo in Manitoba. Riguidel and one of the journalists went to the gym to work out. The two were changing into their workout gear. Suddenly, Riguidel heard the reporter whisper, "There's a man in here. He's watching us in the mirror and he's masturbating."

He was arrested, hiding in the bathroom stalls. Riguidel and her gym partner felt violated and shaken.

By the time she moved to Edmonton in 2014, Maj. Riguidel was showing serious signs of PTSD from the cumulative effects of military sexual assault and the culture that not only kept her silent for years, but made her the brunt of rumours and jokes. She finally sought mental health assistance.

The military was looking to change its rules and its culture, and Riguidel agreed to tell her story at a hearing in front of her superiors. Chilled by the weather and nerves, she was wearing a fleece jacket up until she told her story to a panel of commanders.

While she was testifying in uniform about her painful ordeals, the chief foreign officer from operations sent an email recommending she face discipline for having worn a fleece in the officer's mess. It was the last straw.

Riguidel said, "I've had it. I'm going to release. I can't keep doing this."

Instead, she went back to counselling and came back with a plan to change things from the inside. She asked for and was granted a position with Operation Honour, a mission to deal with "endemic" sexual misconduct in the Canadian military.

Riguidel still has good days and bad days, she says: that's how PTSD goes. But when I met her in Ottawa last month, she seemed strong, keen to show off her new bicycle and her increasing skill on it.

It was Riguidel who convinced MJ Batek to apply to the Invictus Games

They're also part of a private Facebook group called It's Just 700. It was formed by military sexual assault survivor Marie-Claude Gagnon.

When the commission of inquiry into military sexual misconduct issued a report based on stories from 700 alleged victims, the most hurtful backlash came from members of the Canadian Forces. Gagnon saw the serious implications of that rejection.

"It's your own colleagues, your own brothers and sisters in arms.… That made it very difficult. Some people got into distress, there was suicide attempts … so that's why I decided that night very late to create a group."

The goal of the group is to provide support and resources to each other. If someone is reporting military sexual assault, another member will go with them. If someone is feeling suicidal, another member can go to them.

Gagnon sees the promise it can bring.

"I think it gives people a direction, a purpose. That's one of the thing with military sexual trauma you often get pushed aside from the other veterans, because you don't fit in," she said.

There will be challenges for both women. They'll be putting themselves into situations they know can trigger their PTSD symptoms.

Riguidel says her personal goal is not a medal.

"I hope we finish. I hope I finish well. I'd like to be able to say that at the end of it that I've left everything out there."

'It's a huge high'

Batek figures she has already won before she sets foot in Australia. Her training schedule has demanded she come out of her somewhat isolated existence. To be ready, she must go to the pool and attend wheelchair basketball games, places that are teeming with other people.

"Our smiles when we come off that court are huge, and it's a huge high.… You don't have time to think about anything else. All the bad stuff just goes away."

And when the Australian National Veterans Arts Museum made a call for submissions, Batek picked up a brush for the first time in years. She painted a self-portrait from a photograph of herself swimming. She sees herself as the messy image in the water.

"I really need to stop seeing the mess, and I need to start seeing this athlete. And I'm going to I'm going to call myself that. I am an athlete."