'Where do we go from here?': Fatal shooting by Montreal police raises hard questions

The fatal shooting of a 58-year-old black man by Montreal police has renewed concerns from civil rights advocates about the way officers are trained to handle individuals in distress.

"It raises the question, 'where do we go from here?'" said Fo Niemi, a longtime activist and executive director of Montreal's Centre for Research Action on Race Relations.

"Is this a case where race plays a role in this incident? Is it mental health? I think there are a lot of questions here that need to be asked because this is not a situation that should occur too often in this city."

The man has not been identified, but Quebec's independent investigations bureau has confirmed that he was black — a fact that raised immediate concerns among activists.

A screwdriver in each hand

Neighbour Sylvie Dozois, who lives in the same building on Robillard Avenue near Saint-André Street in Montreal's Gay Village, said the man was smashing things in his apartment and yelling before officers arrived at the scene.

"The man was breaking dishes, he was yelling, he lost control," Dozois told CBC News.

When officers arrived at the building shortly after 7 p.m., the man confronted them holding a screwdriver in each hand, according to a statement released Tuesday evening by Quebec's independent investigations bureau, known by its French acronym, BEI.

The bureau, which investigates deaths or serious injuries in incidents involving police, took over the case immediately after the shooting occurred.

Police tried to subdue the victim with a stun gun and rubber bullets, but were unsuccessful. Officers then used their firearms some time between 7:19 p.m. and 7:30 p.m., when Urgences-Santé arrived at the scene.

Will Prosper, a former RCMP officer turned activist, said it appears the man wasn't "presenting a menace to anyone except to his apartment."

He said for someone who is in the midst of a mental health crisis, seeing a gun, even one loaded with rubber bullets, and stun guns would only make matters worse, and shouldn't be the way police de-escalate those kinds of situations.

"That's not what you need to preserve the life of the citizen. It's going to do the [complete opposite], and I think that's probably what happened in this case."

He said the man likely needed someone to talk to and calm him down without the presence of weapons.

"If you're saying 'calm down' and you have the gun pointed at his face, that's not going to work."

Training in de-escalating situations

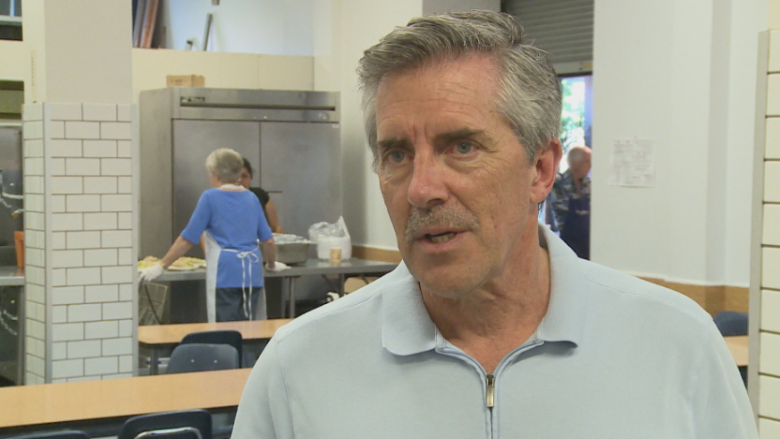

Matthew Pearce, president of Montreal's Old Brewery Mission, said there doesn't appear to be a link between the shelter and the victim, even though the shooting took place in an area frequented by its clients.

Police even called the mission in the wake of the shooting in case there was a link, which Pearce called an important development in police protocol.

"It's the first time they've done this," he said. "That was an important change because in the past there was no such link between the Old Brewery Mission and the police, so we take it as a good sign that ties are stronger than they used to be."

Pearce said it would have been better had they contacted the shelter before the shooting, but acknowledged the situation may not have allowed for that call to be made first.

"Quite often we know the people involved very well and we can intervene or support the police if time permits."

In the wake of the death of Alain Magloire, a black man who was fatally shot by police, Pearce told a coroner's inquest in 2015 that there needs to be closer relations between homeless organizations and police.

Magloire, who suffered from mental illness, was wielding a hammer when he was shot to death by Montreal police on a downtown street in 2014.

Officers to get training this fall

However, it was only two years after Pearce made that suggestion, after the police killing of 38-year-old Mission client Jimmy Cloutier in January, that things started to change.

"I said enough is enough, I want a meeting with the police chief," he said of Cloutier's death.

"I laid out a number of measures, saying we've got to stop these situations where people with mental illness and states of anxiety end up being shot and killed."

Since then, the mission has undertaken three training sessions with police recruits on de-escalating situations involving people exhibiting violent behaviour as a result of mental illness.

Training with active officers is scheduled for the fall.

"When people are showing violent behaviour, the primary motivation is anxiety, not aggression," Pearce said.

"These are people who are anxious, fearful, they need to be calmed down, given space, given time."