The Astronaut Who Stars in the Craziest Show on Cable

“I've seen the planet from space,” Leland Melvin says, with a mix of pride and resignation: He knows what happens when this fact sinks in. Brains become little pink clouds of awe and wonder. Children ask how it works—the body, all the way up there. “They want to know how you use the bathroom in space. That's probably number two,” in terms of what Leland gets asked. “The first one is: Have you ever had sex in space? Sex and pooping.”

Have you…have you ever had sex in space?

“It wasn't me!”

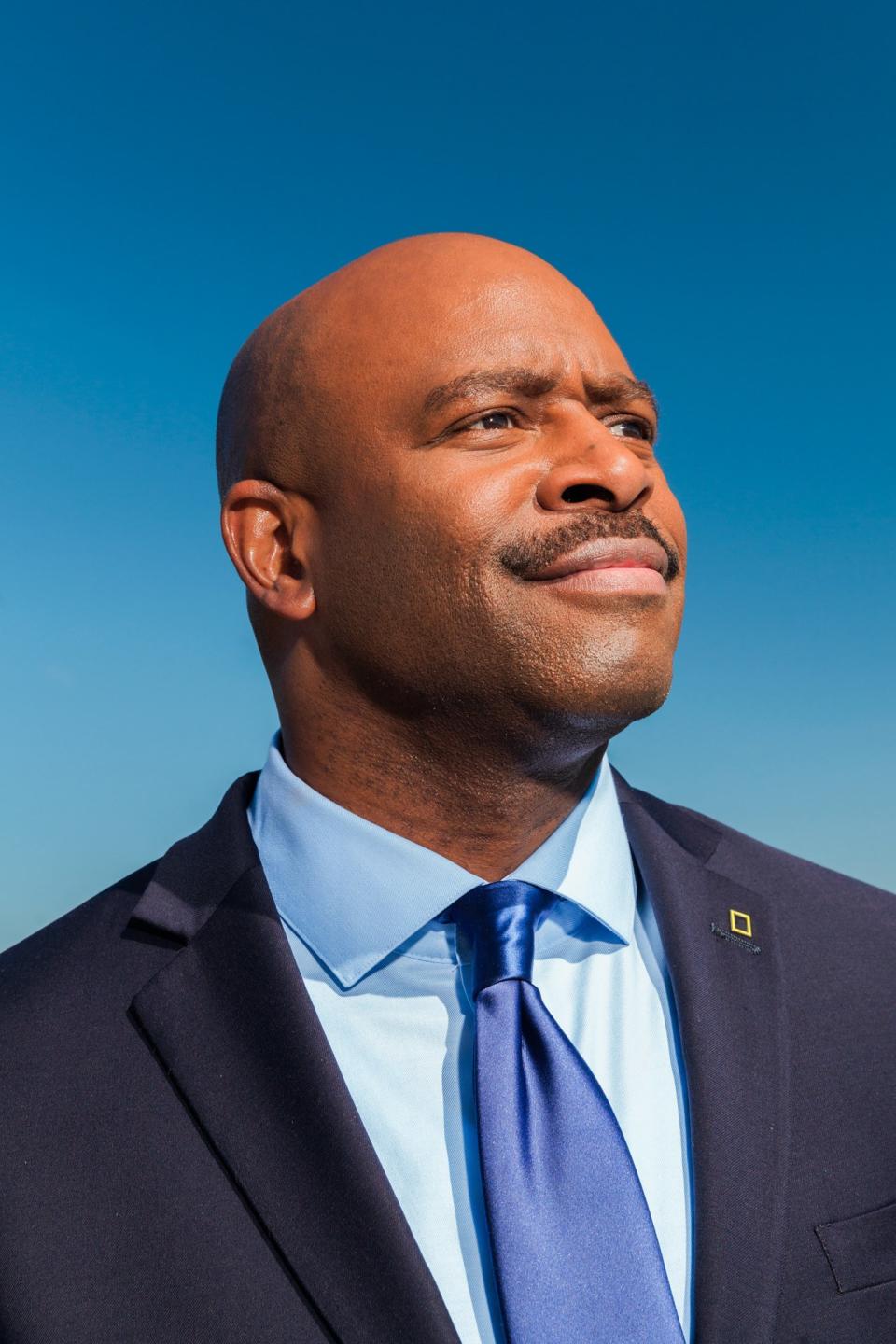

Leland’s in Los Angeles, up here at the Griffith Park Observatory, doing his part to promote One Strange Rock, a documentary series/neon dream from Darren Aronofsky about the planet we live on. The ten-part show, which recently premiered on the National Geographic Channel, stars Leland and seven other astronauts and is narrated by Will Smith, in a way that takes full advantage of having access to Will Smith: “The sun: it is not this big jolly ball of nice, smiling down on us, wishing us all a good day. It is not our friend. The sun is a monster. A planet killer!” Meanwhile volcanoes explode, waves crash, fruit bats nuzzle. Each episode, in an elliptical way, is about how fucking dangerous and crazy nature is—and about how still, stubbornly, life persists. The astronauts are there to attest to both facts. The project is reminiscent of Aronofsky’s unjustly loathed mother!, which was also about the fearsome power of our only home, and also shot like Aronofsky was escaping from a pack of rabid wolves. I recommend this show. It’s crazy.

Around us Los Angeles is opening up into spring, plants re-rushing down hillsides. A gauze of smog lingers in the lower half of everyone’s vision. It’s late March—rent coming due, too many spring breakers crowding the Observatory, and here is Leland Melvin, who has looked down on it all from above. He’s seen the vast beauty of the city, of the country, of the world: what it looks like when you take us out of it. “I've had the luxury of being one of 562 people that have seen our planet from that vantage point,” he says. Five hundred sixty-two people juxtaposed against everyone who has ever lived in the history of this planet. The fraction barely comes to a number at all.

Can I ask you some space questions?

“Sure. Anything.”

Are you somehow different when you come back?

“Most astronauts that I've talked to, they feel this profound sense of connection to the race. Which is the human race, not just the race you are. And they feel this profound connection to the planet. And how do we keep it in a state that's going to be helpful for everyone?”

Is that what you felt?

“I did. I mean, it's hard to explain it. And especially when you train for a year and a half, two years, for this mission—that’s twelve days—it sometimes doesn't seem like it’s real. If you were there for six months, or a year, like Scott Kelly, you see so much more of it. But I trained longer than I was actually in space. So, was it real? Or was it really training? What was it? But when you look back at the pictures and you watch the video, you go, Wow: I was really there.”

Leland’s episode of One Strange Rock is called “Awakening”: “It's about how our brains have evolved over all these millions of years. You think about—90 percent of the creatures on this planet don't have brains. They don't need brains to survive. They can just use neurons that are firing and detecting things. But the show is called One Strange Rock because this is the only rock that we know of that has the kind of intelligent life that we have.”

Leland knows something about brain evolution because Leland lost his hearing. “I went deaf in a training accident” before he even ever went to space, he explains. “In this ear I am completely deaf—my left ear,” he says, pointing. He wears a suit like a guy who’s been wearing uniforms all his life. Sun shines down onto his shaved head. “My right ear is only the speaking frequencies. But the crazy thing is, from a medical, technical standpoint, I should not be able to function in space properly. Because of all the noises and things. But I think our brains and our bodies—you know, when you lose one limb or something, everything else gets stronger? And I just feel like I have this Spidey sense that I'm able to compensate with all my other senses, and be able to perform as this highly, highly functioning, you know, creature.” So highly functioning, it turned out, that the NASA doctors sent him to space anyway, hearing or no hearing. No one else has ever gone up there with what someone else who was not Leland Melvin would call a disability. But he went. Twice. Two trips on the Space Shuttle Atlantis to the International Space Station and back. Twelve days (2008) and 10 days (2009), respectively. Up there, his main job was to operate a robotic arm used to help install new modules to the Space Station. All told, he spent about 565 hours above us.

He’s had the kind of semi-charmed life in which going to space makes sense. Born in Lynchburg, Virginia, in an old and illustrious African-American neighborhood, he grew up an athlete and a scholar: a record-setting wide receiver for the Richmond Spiders with a love for science. “Sports Illustrated published a photo of me in my lab getup during my senior year,” Leland writes in his book, Chasing Space, “holding a beaker of dry ice while mysterious vapors encircled me.” He writes that learning to visualize routes and catching touchdown passes served him well when preparing to operate the 58-foot robotic arm on Atlantis. Out of college, Leland was drafted by the Detroit Lions and was signed by the Dallas Cowboys, before being cut by Tom Landry himself. Then he went to the University of Virginia and got a degree in materials science engineering. When he finally made it to space, he brought with him a Lions jersey, a Cowboys jersey, and a copy of jazz bassist Christian McBride’s Live at Tonic. At dinner with the other astronauts up there, he looked down on Iraq, and Afghanistan, and put on Sade’s “Smooth Operator”—one small, sensual step for mankind.

In time, he became a celebrity in his own right. Leland’s the guy who first introduced Katherine Johnson, of Hidden Figures fame, to that film’s eventual producer, Pharrell Williams. Later, Leland would accompany Johnson to the White House, where Barack Obama gave her the Medal of Freedom. George W. Bush, Venus Williams, will.i.am, Quincy Jones—Leland’s met them all. Or, rather, they’ve met him. He says that not a day goes by when someone doesn’t ask him what it was like, to go up there and come back. And that’s okay, he says. “People paid their tax dollars to send me to space. I feel obligated to share my message: what I felt, what I saw, and how I changed.”

In that case…favorite thing to do in space?

“Looking out the window.”

Favorite space food?

“Dessert—chocolate pudding cake.”

After Leland got back, he became an education administrator for NASA, traveling the country, often in the company of his loyal dogs, Jake and Scout, to spread the gospel of space. Then, in 2014, he retired. Mostly to enjoy his land, back home in Lynchburg, where he spends most of his time now, but also to give speeches, telling his story, hoping to inspire others. He hosted Child Genius, a reality show on A&E in which little brainiacs competed for prizes, and was a judge on ABC’s BattleBots, because in America we reward greatness in strange ways.

By the time Aronofsky and his co-creator on One Strange Rock, Jane Root, approached Leland about the show, he was already a fan of both, he says. Root worked on the BBC’s Planet Earth. Aronofsky, well—“So I did not see mother!,” Leland says, “but I saw Black Swan. You know, it's just different. It just makes you go mmm. But he’s a brilliant, brilliant filmmaker.”

Okay, one more space question then: What do space movies always get wrong about space?

“Okay, so you know when I go to watch a movie about space, I'm not looking with a critical eye, because I'm paying like 15 dollars to see this movie. I want to be entertained. So the things like, in Gravity, when the space shuttle is going around the world in the wrong direction, I'll let that go. But whoever the consultant was, I’m like, Dude, give them their money back, because you missed that!”

But, Leland says, “You know, when I watched Gravity, I was transported back into space. And when I was watching Sandra Bullock on the space station, floating through, I felt like I was back there. I really did.”

Leland smiles, gestures at the two of us, and the city laid out before us, as we look down on it from above. “So art imitating life, life imitating art. Right?”