Beyond long-term care: The benefits of seniors' communities that evolve on their own

The global COVID-19 pandemic has shown Canadians that we need to think differently about how we support older adults. The media and all levels of government have focused heavily on long-term care, and rightly so. However, the vast majority of older adults live at home and plan to remain there for as long as possible.

In a July 2020 Home Care Ontario survey of older adults, 93 per cent of the 1,000 respondents indicated their desire to stay in their own home. No one identified long-term care as part of their future housing plans. Simply put, although necessary for some, long-term care is not where most people choose to live.

It had been clear well before the pandemic that long-term care is costly and woefully inadequate to meet the needs of Canada’s aging population. It is crucial to expand the conversation to consider what other housing solutions exist and how they can be implemented.

Alternative housing models

Essential to the success and acceptability of any housing alternative is the need for older adults to maintain a sense of autonomy and independence, be actively engaged in decisions affecting themselves and their community and have the opportunity to build social networks that can ultimately support one another.

Read more: Most older adults feel at least 20 years younger than they are

Villages and co-housing are two examples of how we can think differently. In the village model found in the United States, older adults living in a neighbourhood of single dwelling homes come together as a group to organize paid and volunteer services.

Originating in Europe, co-housing brings together younger and older adults in clusters of homes or apartments built around shared spaces. Members work together to manage common spaces and support each other through group activities such as communal dining.

Naturally occurring retirement communities

Naturally occurring retirement communities (NORCs) offer a third example with enormous potential. Unlike the village or co-housing models, NORCs are unplanned communities that have a high proportion of older residents.

For example, individuals in a specific neighbourhood may have aged together as a community, or an apartment building in a walkable neighbourhood may attract older adults moving from single family homes. On their own, NORCs are simply a way to describe a community’s demographic profile, however, they can be seen as a critical piece of the solution.

Researchers have referred to NORCs as “untapped resources to enable optimal aging at home” with the potential to build social networks and integrate supportive community programs. Studies have demonstrated the benefit of these communities to building social networks and increasing participation in daily activities. There are well documented examples of NORCs with social support programs in New York and other U.S. states. To date, there has been very little focus on NORCs in Canada and only a handful of documented examples.

NORCs in Ontario

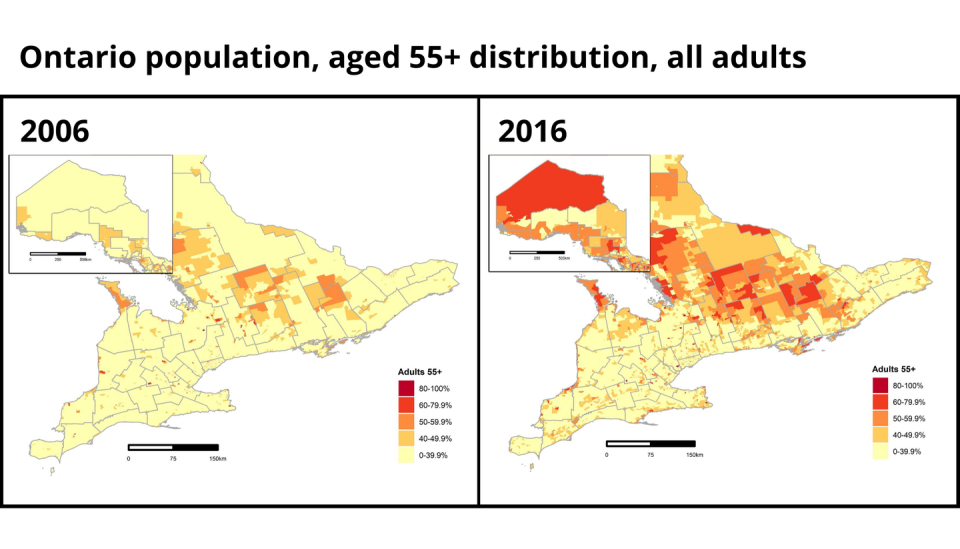

We examined the make-up of Ontario neighbourhoods using Statistics Canada’s dissemination areas — which are small, stable geographical areas with 400-700 inhabitants — to identify the prevalence of NORCs in the province.

We found the proportion of neighbourhoods with at least 40 per cent older adults (age 55 and older) dramatically increased from 8.7 per cent in 2006 to 20.1 per cent in 2016. Although the prevalence of NORCs has increased overall, NORCs vary in frequency across the province. In Central Ontario, an incredible 37 per cent of neighbourhoods are considered NORCs, whereas in the highly populated Golden Horseshoe area capping the western end of Lake Ontario, NORCs make up 14 per cent of neighbourhoods.

These findings provide a literal and figurative map on which we can plan a shift in the way we support older adults: reorienting services to focus on building socially connected NORCs, creating resource hubs in NORCs and developing NORCs as age-friendly communities. Given the anticipated growth of the older adult population over the next decade we can expect the number of NORCs to continue to increase.

A NORC Oasis

The Oasis Senior Supportive Living program is one Canadian example of how NORCs can be leveraged to bring supports to older adults. Oasis was created by older adults in one apartment building in Kingston, Ont., a decade ago and, together with a community board of directors and on-site Oasis co-ordinator, they run community activities, including physical and social activities and congregate dining in a common space donated by the building’s landlord.

Preliminary results show that Oasis increases physical activity levels and decreases social isolation, as well as leads to a decrease in use of the health-care system, particularly home-care services. Over the past two years, through a partnership between the Oasis members and board of directors, Queen’s University, and McMaster and Western universities, we have spread Oasis to six new NORCs in Ontario.

As the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions appear to be a collective reality for the near future, it is essential that we explore how to support older adults in their communities. NORCs exist, we can easily identify them and it is now time to capitalize on these as a real solution by considering NORCS as an option for how we support older adults and providing resources to strengthen existing and potential NORCs.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts.

Read more:

How we rely on older adults, especially during the coronavirus pandemic

The coronavirus exposes the perils of profit in seniors’ housing

Catherine Donnelly received funding from Baycrest Centre for Aging, Brain Health and Innovation, Ministry of Health, Ministry of Seniors and Accessibility

Vince DePaul has received funding from the Centre for Aging and Brain Health Innovation (CABHI) led by Baycrest, and the Government of Ontario through the Ministry of Seniors and Accessibility and Ministry of Health.

Paul Nguyen and Simone Parniak do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.