Bird flu in Florida? Safe to consume chicken and milk? How the outbreak can affect you

A bottlenose dolphin. A bald eagle. The Everglades’ beloved white Ibis.

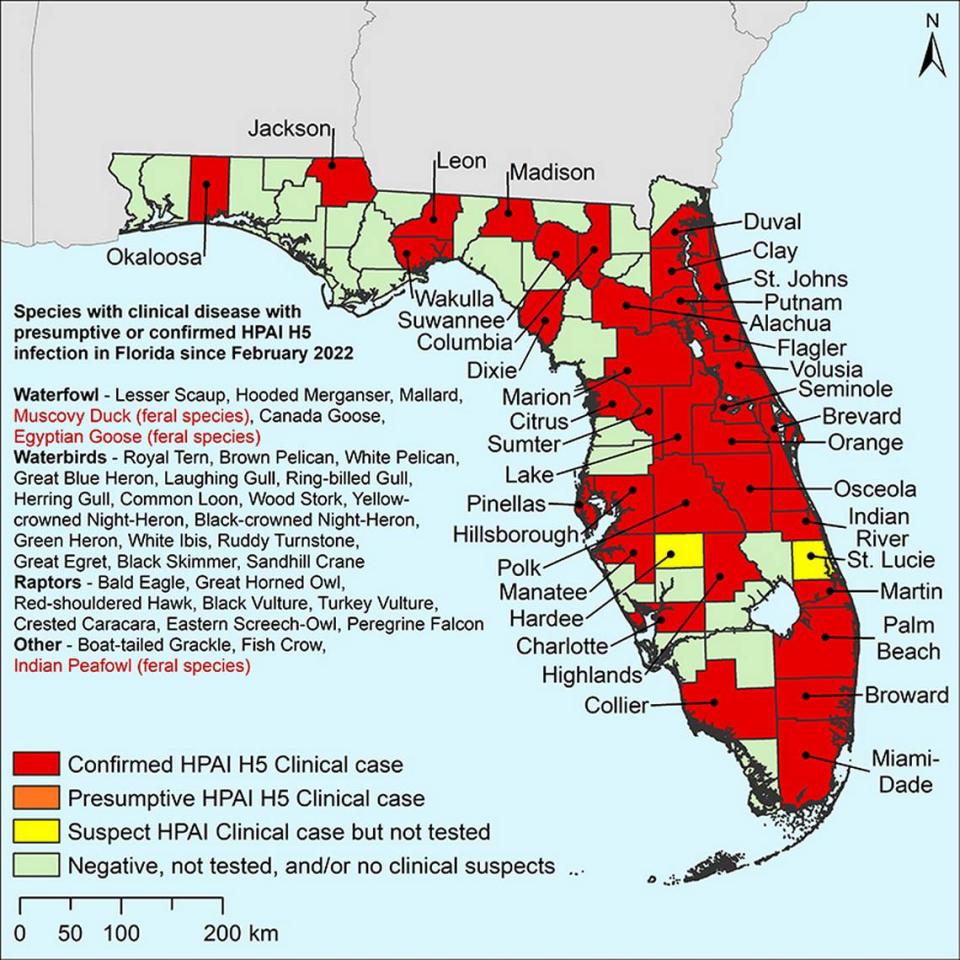

More than 4,670 animals in Florida have been killed since the bird flu outbreak began in 2022, either because they were infected with the virus or were part of an infected flock, according to the most recent data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

The widespread virus has affected more than 90 million birds in the country, including some in Miami-Dade, Broward and Palm Beach counties. And while the virus has long been associated with poultry and wild birds, scientists have detected it in other species in the U.S., including cows, foxes, skunks, big cats and bears.

In Florida, bird flu was even detected in a dead bottlenose dolphin, making it the first known cetacean to fall ill with the virus, according to researchers from the University of Florida. And while the U.S. has confirmed three cases of people infected with H5N1, federal officials say the transmission risk for the general public remains low.

But they’re still closely monitoring the disease and are urging people to take precautions if they’re interacting with possibly infected animals.

“This outbreak has shown that the U.S. needs to improve its ability to respond to new and emerging infections in order to minimize the chances of a new pandemic,” said Andrew Pekosz, professor and vice chair of the W. Harry Feinstone department of molecular microbiology and immunology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Pekosz investigates the replication and disease potential of respiratory viruses, including influenza, COVID-19, and other emerging viruses.

Here’s what to know:

What is the risk level of bird flu infections in humans?

The U.S. has confirmed three cases of humans infected with the highly pathogenic avian influenza A virus known as H5N1. The two most recent cases were reported this year and involve dairy farm workers. The most recent case, reported in May, occurred in Michigan, the other happened in April in Texas. Both people worked on farms that had infected cows.

The first human case of H5N1 recorded in the U.S. during this outbreak happened in 2022 and involved a worker in Colorado who was involved in killing possibly infected poultry.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the country’s top public health agency, says there’s a low risk that the disease will spread to more people.

The National Institutes of Health on Friday also noted that the virus, called H5N1, which has circulated in the country for the past several years and has infected more than 50 animal species, has “so far shown no genetic evidence of acquiring the ability to spread from person-to-person.”

However, officials say they are closely monitoring the disease spread and are urging people to avoid contact with sick or dead animals to reduce the risk of infection. They’re also urging people to avoid unprotected exposures to animal poop, litter, raw milk or other items that have been touched by birds, cows or other animals that are suspected or confirmed to be ill with the virus.

Bird flu is infecting cows. Is it safe to drink milk?

If the milk is pasteurized, it should be safe to drink and cook with, according to Dr. Meghan Davis, a former dairy veterinarian and an associate professor in the department of environmental health and engineering at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Nearly all milk you’ll find at the grocery store has undergone pasteurization to reduce contamination, a treatment process federal regulators say is effective against killing the bird flu virus.

Experts like Davis are cautioning against drinking and using raw milk however, as the product could be contaminated with the virus and lead to illness. Mice given droplets of raw milk from infected cows as part of a study, for example, fell ill and were later found to have high levels of the virus in their respiratory organs, similar to H5N1 infections in other animals. The study was recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine and “suggests that consumption of raw milk by animal poses a risk for H5N1 infection and raises questions about its potential risk in humans,” according to the National Institutes of Health.

Raw milk could also increase the infection risk for pets, with experts from Johns Hopkins noting that there are reports of cats on dairy farms falling ill after consuming raw milk from infected cows.

What about pasteurized milk and other dairy products?

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration recently tested 297 samples of dairy products, including milk, cheese, cream and yogurt, collected from stores across 17 states including Florida, and were produced at processing locations across 38 states.

The samples, which were collected in April, were selected to be representative of processors in states that have and have not had infected cows. Tests did not detect any live, infectious virus in the products, the FDA said in its May 10 update.

According to the most recent data from the USDA there have been no reported inflections in Florida dairy cows. But it’s important to remember that just because you buy milk in a Florida store, it doesn’t mean the milk came from a Florida cow or was pasteurized in the state. Milk can come from cows on farms in different states and be pasteurized in other states before making it onto your grocery store’s shelves.

“Commercial milk is typically pooled from many dairy farms, pasteurized in bulk and distributed to a variety of states,” the FDA said. “Even if a sample was collected in one particular state, the milk in a consumer package could have come from cows on several farms located in several states, pasteurized in a different state from the states where the milk was produced, and available for purchase in yet another state.”

While nearly all commercial milk, cheese and other dairy products are pasteurized, look for the word “pasteurized” on the label to double check. If you don’t see it, there’s a chance the product contains raw milk. There are other milk alternatives you can turn to as well including soy, almond, oat and coconut milk.

Is it safe to eat meat, eggs, chicken and other poultry?

It’s safe to eat meat, eggs, chicken and other poultry as long as the food is properly prepared and cooked, according to the Johns Hopkins experts and the U.S Department of Agriculture.

The USDA says it has several safeguards in place, including testing of flocks, to ensure that infected birds do not make their way into the country’s food supply. The agency has similar safeguards in place for cattle and requires for poultry and cattle to be inspected for signs of disease before and after slaughter.

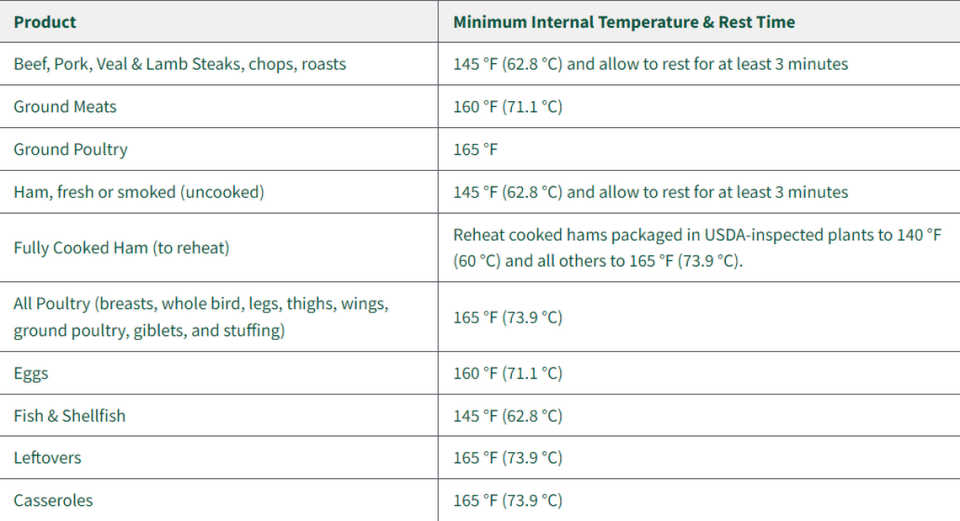

It’s also important to make sure your food is cooked properly to reduce the risk of foodborne illness. USDA recommends using a food thermometer to make sure the poultry your cooking has reached an internal temperature of at least 165 degrees F. This heat can kill any foodborne germs that might be present, including the avian influenza viruses.

What about beef?

The USDA has not found traces of the virus in ground beef samples collected from retail outlets where cows have tested positive, according to the New York Times.

The federal agency on Friday announced that beef tissue from a sick dairy cow had tested positive for the bird flu but reiterated that because the cow was condemned due to signs of sickness, its meat had not entered the food supply.

The positive test was part of a study the USDA conducted on beef safety. It tested beef tissue from 96 sick dairy cows and only one tested positive. The agency has also conducted a study to test how much heat would be needed to kill high levels of H5N1 in ground beef patties.

What it found: No virus was present in the burgers that were cooked to the recommended temperatures of 145 degrees, which is medium, or 160 degrees, well done. Rare burgers cooked to 120 degrees — which is well below the USDA’s recommended cooking temperature — still had traces of the virus present but it was at greatly reduced levels, the NYT reported.