Science and Weather

Science and WeatherLife discovered deep beneath Antarctic ice may provide a model of alien life

Researchers have revealed for for the first time an ecosystem hidden beneath the West Antarctic ice sheet that may help focus our search for life beyond Earth.

According to the new study in the journal Nature this week, Antarctica’s sub-glacial environment is our planet's largest wetland, equal to 9% of the Earth’s land. However, unlike the habitats we are familiar with on the surface of our planet, this one is dominated completely by microorganisms – as many as 4000 species.

By using hot-water drilling, researchers were able to bore down through 800 meters of ice and retrieve pristine samples from remote Lake Whillans – located only 640 km from the South Pole. The lake is estimated to have remained trapped in darkness and isolation from the outside world for thousands of years. In fact, the team believes that life may have existed in this extreme environment, completely cut off from the Sun’s energy, for between 120,000 years to a million years.

The idea of hidden lakes beneath thick layers of ice on the frozen continent really only took off in the 1990s when ground-penetrating radar and seismic surveys first revealed them. While similar samples were also retrieved a couple of years ago by Russian scientists from the largest and deepest of the these subglacial environments, Lake Vostok, this new discovery is the first time we have found clear evidence for an entire ecosystem that has been cut off from the outside world for many millennia.

Scientists have scoured the world in some of the most extreme environments and have always found something eking out a living – be it the dark depths of the ocean, inside toxic volcanic vents or on arid deserts.

In the case of these Antarctic subglacial lakes, these microbes may be relegated to the lake bottom, deep within the sediment. So the big mystery is – what do these little critters eat?

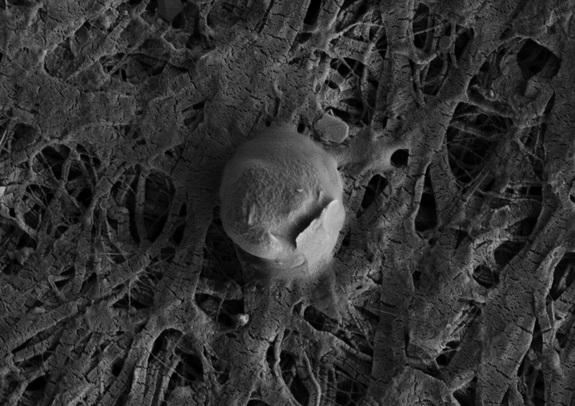

The best guess so far is that they get their nutrients directly from the melting ice, sediments or maybe even from rocks. Glacial crushed bedrock offer the microbes food, as they are able to attach themselves to the released minerals and dissolve them – essentially ‘eating’ the rocks.

For scientists who were expecting to help define the limits of life, it seems that we have been able to push that boundary even further. Finding this evidence of life, modest as it is, in these lakes tells scientists that life can indeed exist isolated from the rest of our planet’s rich biosphere for hundreds of thousands of years. It also offers up clues to where life may have evolved beyond Earth in far away places in the solar system.

The notion of primitive life eating rocks to survive, for instance, now gives traction to hopes of finding current life underneath the surface of Mars.

Also, space probes have been finding strong hints of vast oceans trapped under thick layers of ice on the moons of Jupiter and Saturn. Both Europa and Enceladus are now leading candidates for possible future life-seeking missions.

NASA already has on its drawing boards an audacious plan to send a lander to Europa to drill through its ice sheet and send down a robotic submersible to explore its vast, salty ocean. Hidden in the darkness along its bottom, volcanic vents may produce enough heat and nutrients to offer a comfy environment to all kinds of alien life.

Geek out with the latest in science and weather.

Follow @YGeekquinox on Twitter!