Canada's commitment to eradicate hepatitis C hindered by COVID-19, says Calgary doctor

Eradicating hepatitis C by 2030 — a virus that affects the liver and can cause severe damage if gone undetected and left untreated for years — has been Canada's goal since 2016.

With proper medication, experts say, it can be cured within a few months.

But when the pandemic hit and everyone's attention focused on COVID-19, a Calgary liver expert says testing and treatment for hepatitis C slowed to a trickle, meaning Canada's ability to reach its commitment was setback by a huge margin.

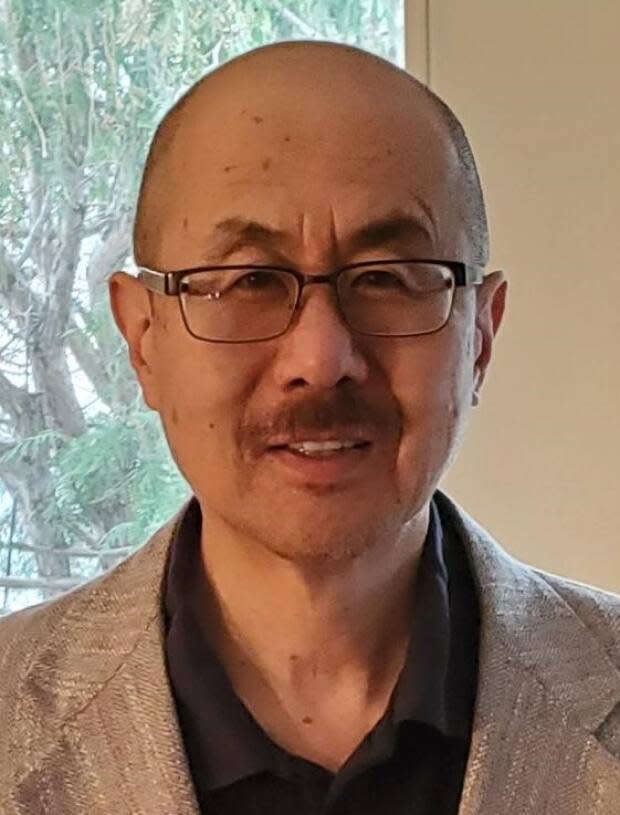

"We probably won't eliminate hepatitis C, which is a curable disease, by 2030, maybe 2035, maybe 2040, I don't know," said Sam Lee, a professor at the University of Calgary's department of medicine and an expert in hepatology.

Lee said he's especially concerned for the higher-risk populations, including Indigenous people, IV drug users, prison inmates, people born between 1945 and 1975, and immigrants arriving from a country with a high infection rate.

According to the Canadian Network on Hepatitis C, nearly 50 percent of Canadians don't even know they have it.

"Eventually that can lead to horrible things like cirrhosis, which is permanent scarring and damage to the liver, and liver cancer — and people end up dying in three or four or five decades," said Lee.

So that's why he and other advocacy groups, including Action Hepatitis Canada, the Canadian Liver Foundation and the Canadian Association for the Study of the Liver, are marking May 11th, the inaugural Canadian Viral Hepatitis Elimination Day in Ottawa.

"What we want to do today is try to draw attention to things, there's other viruses out there besides COVID-19," Lee said.

"And now that COVID is kind of hopefully settling down a bit, we want people to go out and get tested ... because the treatment, the pills, have a 98-per-cent cure rate."

Eliminate disease & stigma

Kate Dunn is a University of Calgary associate researcher who works with Lee on a project that focuses on hepatitis C screening and treatment, via Zoom, in remote and Indigenous communities.

Dunn said there is a lot of stigma around hepatitis C because of the way it can be contracted — through blood and body fluids. High-risk groups include IV drug users, prison populations and marginalised groups.

"That old myth that, oh, hepatitis C is like HIV, and, you know, it's in that family of of dirty sex disease, don't talk about it," said Dunn.

But Dunn said it can also be contracted from using dirty manicure tools, getting tattoos or piercings in a non-sterile studio, or from a blood transfusion pre-1992, before screening for the virus was done.

"It is important to shift that story that this is not something you deserve, that this is something that can happen to anyone," said Dunn.

Because of that stigma, she said, some people are hesitant to come forward to get screened — potentially allowing the virus to continue to circulate in a community or cause further harm.

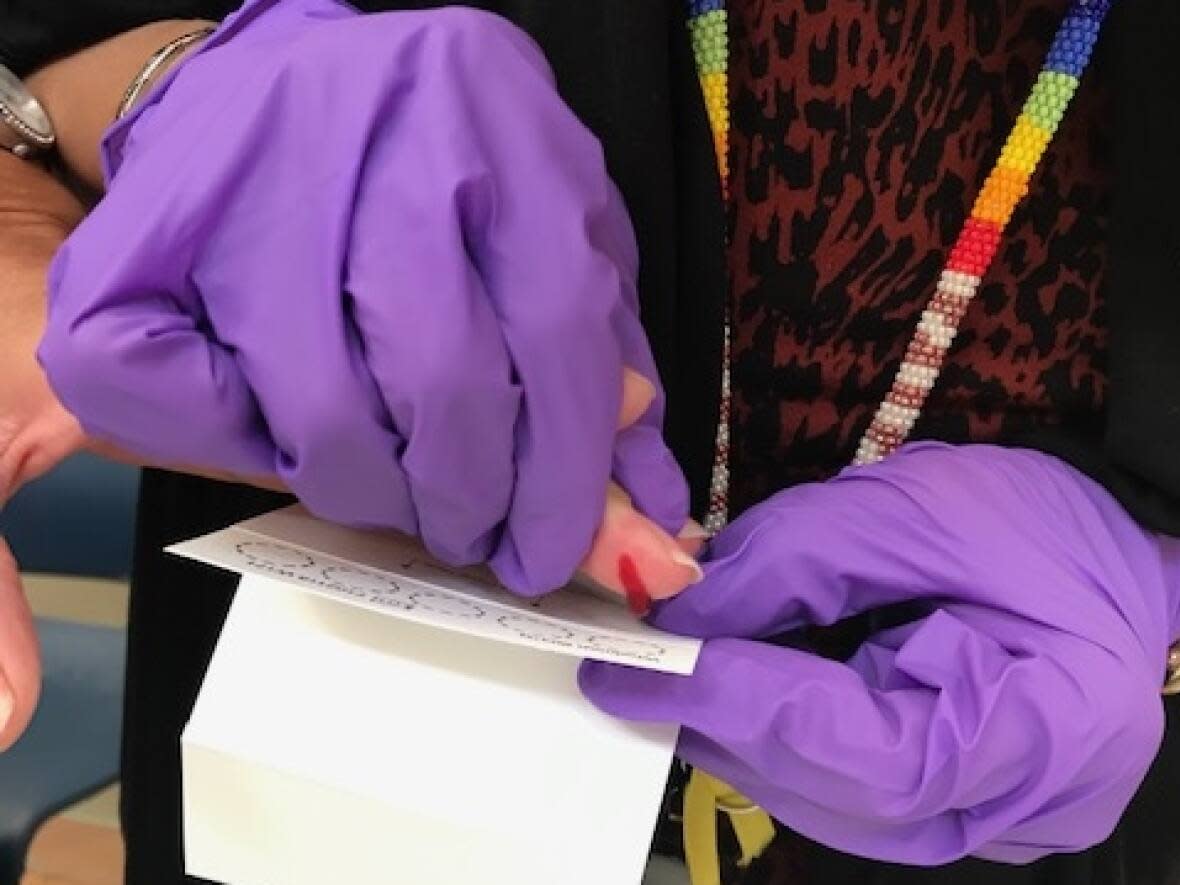

Currently, those who believe they are at risk can ask for a test at their doctor's office, or at some local agencies such as CUPS in Calgary.

But Dunn would like to see routine screening across Canada — and more awareness among Canadians.

"Start talking about it, find some information, increase your awareness and comfort level with it, and then tell somebody else, because that's how we're going to make a difference and eliminate it," said Dunn.