Canadian researchers turn to wastewater tests at long-term care homes to detect COVID hot spots

Several Canadian universities are preparing to test wastewater from long-term care homes in Ottawa, Toronto and Edmonton to get early warnings of COVID-19 outbreaks.

Researchers in municipalities in six provinces are already testing wastewater for traces of SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for the disease. Many of those infected shed the virus through their feces, even if they don't have symptoms, according to researchers.

But that kind of testing uses samples from wastewater facilities and shows the results for an entire community. Researchers currently aren't able to pinpoint the exact locations where outbreaks are flaring up.

"We all go to the toilet, whether you have COVID or not, whether you're symptomatic or not," said Dr. Doug Manuel, a senior scientist at The Ottawa Hospital involved in the program.

"It's a way of doing a survey or census on everyone, every day. Instead of testing thousands of people, we can just test the sewer system once a day at the treatment plant."

The federal government's COVID-19 Immunity Task Force is supporting efforts by several labs to use that technology to detect outbreaks occurring where the most vulnerable Canadians live.

The University of Ottawa, the University of Toronto and Ryerson University are working together on the project and their work is being supported by that task force, said Bernadette Conant, CEO of the Canadian Water Network. A team at the University of Alberta also plans to start testing at long-term care homes with federal support, she said.

Conant's non-profit organization started a wastewater coalition in Canada to help coordinate the work of researchers across the country, and to provide technical guidance to scientists, laboratories, wastewater utilities and public health authorities.

"You want to know the neighbourhoods where testing might need to increase, or where there are hot spots," said Conant.

Health officials in the U.S. say such sampling may have helped them head off an outbreak at the University of Arizona. When tests of wastewater at the dorms came back positive for COVID-19, two asymptotic students were identified and quickly quarantined.

'It could catch an early signal'

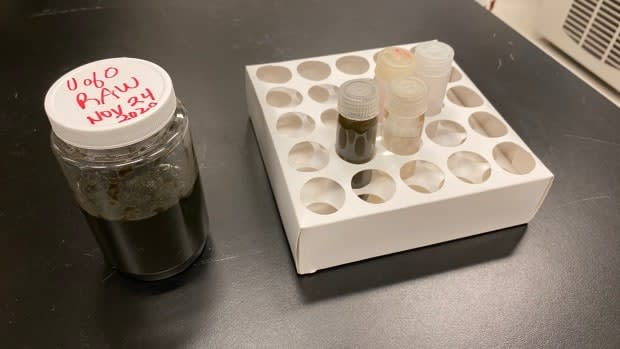

Robert Delatolla is an engineering professor and researcher co-leading the University of Ottawa's program. His work monitoring the capital's wastewater daily and posting the results online has caught the attention of the chief science advisors to the prime minister and the Public Health Agency of Canada.

Delatolla's group plans to test samples from individual sewers connected to long-term care buildings in Ottawa and the Greater Toronto Area.

"It could catch an early signal," he said. "It could be like a smoke detector signaling that things are starting to come online, outbreaks are happening.

"By being able to monitor a facility that is doing well and doesn't have an outbreak, the wastewater is a potential tool to actually catch when that outbreak first happens."

Delatolla points to tests his team conducted on July 17 which detected COVID-19 levels suddenly increasing 400 per cent in Ottawa's water treatment plant. That surge was discovered in the wastewater two days before Ottawa Public Health reported an increase in the number of people testing positive, he said.

Testing could detect when an outbreak has stopped

Dr. Alex MacKenzie is a senior scientist at the CHEO Research Institute, which is co-leading the team in Ottawa. He said the wastewater testing has been acting as the "belt and suspenders" supporting the data epidemiologists are obtaining through swab testing sites — data he said is "flawed" because not everyone is getting tested.

"It's hard to get a clear lens on exactly how many are infected in the community," said MacKenzie. "We have the advantage here in Ottawa of actually having a different window."

Researchers said that more than 910,000 Ottawa residents are now providing them with testing samples through the wastewater system — more than 90 per cent of the city's population.

MacKenzie said applying wastewater testing to long-term care homes could be a way to ease the strain on front line workers.

"It will be a way of monitoring the outbreak within a facility and knowing when it actually has stopped," he said. "So it will offload some of those individual testing resources that we do, ideally."

'You would be able to intervene faster'

Currently, long-term care homes are conducting surveillance testing on residents every week or two weeks. Residents are sometimes missed in that timeframe, said Dr. Vera Etches, Ottawa's chief medical officer of health. Wastewater testing could help monitor for COVID-19 between those testing periods.

"You would pick up the signal potentially earlier," she said. "So you would be able to intervene faster."

Dr. Etches said that's important because "there can be a lot of exposures and a lot of spread" when people are asymptomatic, or in the days before patients start exhibiting symptoms.

"Eighty-eight per cent of people who have died from COVID so far have been residents of long-term care homes," she said. "So this would be an opportunity to try to limit that outcome."

But there are still challenges with the testing.

Delatolla said rainwater can dilute the samples and chemicals in wastewater can alter them, causing variance in the samples. Public health officials also don't know yet how quickly the virus shows up in wastewater once someone contracts COVID-19, said Dr. Etches.

She said she is using both COVID-swab results and wastewater testing to get a better picture of outbreaks, because the science isn't advanced enough to depend on wastewater tests alone.

The COVID-19 Immunity Task Force said funding agreements for its most recent set of studies aren't finalized yet, so it can't publicly comment right now.