What are the chances of a major earthquake hitting St. Louis and the metro-east?

Do you have a question about U.S. history, popular culture, celebrities, trivia, other topics you are curious about in this wondrous world of ours? Please send your questions to newsroom@bnd.com and we’ll try to find the answers. Here’s today’s topic:

Were you awakened by the 2008 earthquake centered near Mount Carmel, Illinois?

It was a 5.23 magnitude earthquake that struck at about 4:37 a.m. on April 18, which happened to be the 102nd anniversary of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake with a 7.9 magnitude that caused an estimated 3,000 deaths.

This year’s Easter Monday anniversary of the Mount Carmel earthquake is a stark reminder of the earthquake threat in the Midwest. So was the much smaller earthquake reported in the St. Louis area on Friday, April 29, 2022.

While the Mount Carmel quake didn’t cause any serious injuries, it prompts questions about the chances of “the big one” hitting our region and what you should do if you feel “the shake.”

The Mount Carmel earthquake occurred about 150 miles from St. Louis near the border of Indiana. It was in the “Wabash Valley seismic zone” that covers southeastern Illinois and southwestern Indiana.

It’s near the more widely known area called the “New Madrid seismic zone,” which surrounds a similarly named Missouri town on the banks of the Mississippi River about 164 miles south of St. Louis.

This seismic zone covers the far southeastern section of Missouri, the extreme southern tip of Illinois, the far western tips of Tennessee and Kentucky and the northeastern section of Arkansas.

This New Madrid area produced a series of three major earthquakes on Dec. 16, 1811 with an estimated 7.6 magnitude; on Jan. 23, 1812, with a 7.5 magnitude; and on Feb. 7, 1812, with a 7.8 magnitude.

President James Madison in Washington, D.C., was awakened by the Dec. 11, 1811, quake and the Feb. 7, 1812, earthquake was probably the one most widely felt across North America, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. The New Madrid earthquakes are believed to be the largest earthquakes east of the Rocky Mountains in the history of the United States, according to a report by the Missouri State Emergency Management Agency.

At the time of the 1811 and 1812 quakes, the population of the St. Louis area was about 5,700. Today, millions of people live where a repeat event would be most acutely felt.

Bob Bauer, principal engineering geologist for the Illinois State Geological Survey, said the Feb. 7, 1812, earthquake caused the surface to rise about 30 feet at the Mississippi River and disrupted the river flow.

“The ground surface moved up I think about 30 feet and that cut across the Mississippi River and that’s the stories of the river running backward because the fault cut across there and dammed up the Mississippi River,” Bauer said in an interview with the BND.

Here’s a question and answer series of what you need to know about the earthquake threat in the Midwest and the New Madrid fault:

What’s the probability of a repeat of the 1811-1812 New Madrid quakes?

The U.S. Geological Survey reports there is about a 10% chance of a 7.5 to 8 magnitude earthquake in the next 50 years.

For a New Madrid quake of a 6 magnitude, there is about a 30% chance in a 50-year window.

What could we expect in the metro-east?

An “intensity” scale that uses Roman numerals measures what impact people would experience in an earthquake.

In a repeat of the 1811-1812 earthquakes, the greater St. Louis area would experience a VII to VIII on an intensity scale that ranges from I to X, according to the scaled used by the U.S. Geological Survey.

Here are some of the things you can expect to happen in the VII range: “Difficult to stand. Furniture broken. Weak chimneys broken at roof line. Large bells ring. Concrete irrigation ditches damaged,” according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

Here’s what you can expect to happen in the VIII range: “Steering of motor cars affected.” Some masonry walls fall. “Twisting, fall of chimneys, factory stacks, monuments, towers, elevated tanks. Frame houses moved on foundations if not bolted down…Branches broken from trees. Changes in flow or temperature of springs and wells.”

How often has the New Madrid fault had major earthquakes like the ones in 1811-1812?

Prior to the 1811-1812 New Madrid earthquakes, geologists estimate there were significant earthquakes five other times in the past 5,000 years in this seismic zone.

“This has happened before, multiple times,” Bauer said.

The occurrences fall in a range of plus or minus 100 to 200 years around a target year, Bauer said. The targeted years are 1450, 900, 1 A.D., 1050 B.C. and 2350 B.C.

Can scientists predict when the next one will occur?

Perhaps you remember when Iben Browning, described by St. Louis Public Radio as a “a self-proclaimed climatologist,” predicted a major earthquake around Dec. 3, 1990, on the New Madrid fault. Needless to say, Browning was wrong.

“It can’t be predicted,” Bauer said of a major earthquake. “What we talk about is preparing for the worst. Then you’re prepared for different things that are thrown at you.”

Minor quakes recorded deep in the ground occur constantly in the New Madrid seismic zone.

The New Madrid seismic zone averages about 200 earthquakes per year with a magnitude of 1 or greater. Tremors of a magnitude 2.5 to 3 are large enough to be felt and are reported annually, according to a report by the Missouri State Emergency Management Agency.

A U.S. Geological Survey map shows that over 20 earthquakes have been recorded in the New Madrid area in the past month.

Two earthquakes have been recorded in Illinois in the past month. One was a 2.3 magnitude located north of Edwardsville and southwest of Hamel on March 25. It was about 10 miles below the surface and no one reported feeling it. The other was on Wednesday near Springerton, Illinois, which is about 118 miles east of St. Louis.

This was a 2.6 magnitude and 20 people reported to the U.S. Geologicial Survey that they felt the earthquake, which occurred about nine miles below the surface. While only 20 people reported this one, the Mount Carmel earthquake in 2008 generated about 40,000 reports to the “Did you feel it” online system monitored by the U.S. Geologicial Survey.

In California, earthquakes occur along the San Andreas fault, where two of the Earth’s tectonic plates clash. In contrast, the quakes in the New Madrid area occur in “cracks” in the tectonic plate under North America, Bauer said.

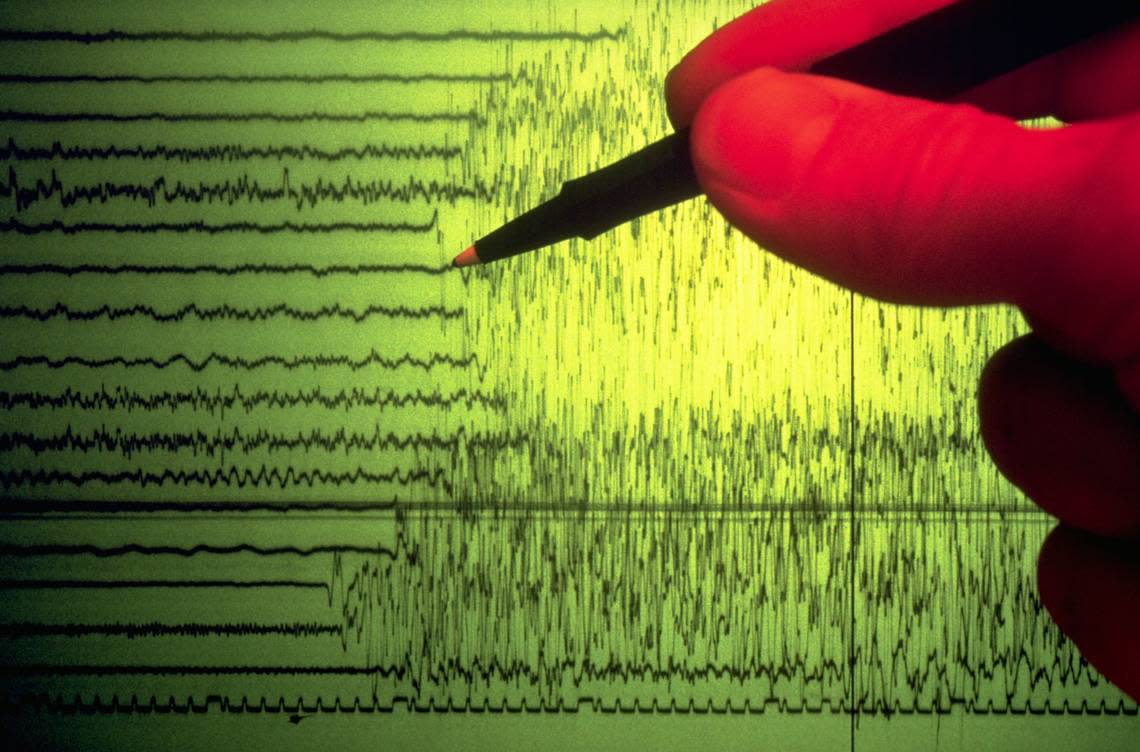

An earthquake occurs when “rocks forming the Earth’s crust slip past each other along a fault,” according to an Illinois hazard mitigation plan. This movement produces vibrations, or seismic waves, which cause the shaking or “quaking” that can last 10s of seconds to a few minutes.

The U.S. Geological Survey has produced a 30-second video that shows a computer simulation of ground motion caused by a 7.7 magnitude earthquake in the New Madrid seismic zone. Go to earthquake.usgs.gov and type in “New Madrid computer simulation” in the search box on the lower left of the home page.

What should I do if I feel shaking in an earthquake?

Public safety experts urge you to follow this mantra:

Here are more tips from ShakeOut.org, which is sponsored in part by the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the U.S. Geological Survey and the National Science Foundation:

Drop to your hands and knees where you are and don’t run outside.

▪ This position protects you from being knocked down and reduces your chances of being hit by falling objects.

▪ If you are in a wheelchair or walker, lock the device in place.

“Cover your head and neck with one arm and hand.

▪ If a sturdy table or desk is nearby, crawl underneath for shelter.

▪ If no shelter is nearby, crawl next to an interior wall.

▪ Stay on your knees; bend over to protect vital organs.”

Hold on to the table or desk until the shaking stops.

▪ “Under shelter: hold on to it with one hand; be ready to move with your shelter if it shifts.

▪ No shelter: hold on to your head and neck with both arms and hands.”