How a childhood sexual abuse survivor found 'stability' through supportive housing

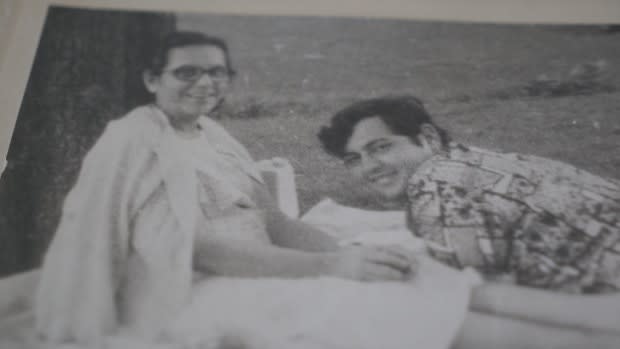

For Sa'ad Talia, being shuffled between cities at the whim of his wealthy parents was the normal pace of his life growing up in Pakistan.

It was also a routine filled with terror.

After once being sent away to stay in a town without his parents, Talia was sexually abused by a servant. His mother's reaction was violent punishment — for her son, not his abuser.

WATCH: Childhood sexual abuse survivor Sa'ad Talia talks about the importance of supportive housing:

"My father never touched me," Talia recalls. "My mother used to beat me up, to the point of drawing blood."

That childhood trauma enveloped Talia's life for decades to come, derailing his later efforts to study in the United States and earn a degree.

For years, he suppressed the painful memories with alcohol and drugs, all while battling a trio of life-altering mental illnesses: depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

After moving to Toronto in 2000, Talia wound up checking into a rehab centre. Then, in 2008, his already-fragile life was upended when he lost both his Bay Street banking job and his downtown apartment.

"I went through my usual thing, which was to retreat completely," he says. "Go to sleep. Not wake up. Until the bailiff was at the front door."

Talia wound up living precariously in an unheated basement, facing constant threats of eviction from his landlord, and veering close to homelessness. Then he learned of another option.

It was a supportive housing program in a boarding house, operated by a local non-profit, which offered mental health and addiction services to residents to ensure they could live independently in their homes.

In early 2009, he moved in. He's been living within the city's patchwork supportive housing offerings ever since, and has been in his current unit in a Weston apartment building for nearly five years.

On this afternoon in February, the 63-year-old is staying warm inside the high-rise home, spending time with his dog, Lulu, a puppy- mill rescue, and watering his collection of plants, their branches all reaching toward the sunlight streaming through his floor-to-ceiling windows — a room full of life, and "contentment," Talia says.

It's a set-up that offers not only a roof over his head, which he pays for through the Ontario Disability Support Program, but regular check-ins, social gatherings, and a network of services, helping him navigate the health-care system.

"People like me need this because we have things to contribute," Talia says. "But if we don't have stability, what can you contribute?"

It's a question the city is asking as well, and hoping to answer through a new plan to offer its own supportive housing for the first time.

City hoping to create 600 units each year

The plan outlines how the city itself can create 600 units each year starting in 2020, while pushing for federal and provincial partnerships to hit a 1,800-per-year target.

It recommends renovating and converting existing units, including shelter sites and Toronto Community Housing rooming houses and vacant units, while connecting wraparound support services with private rental housing.

Now approved by the planning and housing committee, and awaiting a final stamp of approval from council, the plan would mark a dramatic change in Toronto's level of involvement in creating supportive units, which remain under provincial jurisdiction.

"We've never, never built supportive housing in this city," says committee chair Coun. Ana Bailao.

But, she adds, a large number of people who are experiencing chronic homelessness — which the federal government defines as being homeless for six months or more — are already using Toronto's overflowing shelter system as "de-facto housing." It's around 23 per cent of clients, according to city officials, which equals more than 5,000 people each year.

Many of them, advocates say, are struggling with the same kind of trauma, addiction, and mental health issues that long prevented Talia from living a stable life.

So why not give those people actual housing instead, coupled with services to manage their mental health or addiction issues, so they don't wind up stuck on the streets?

"It's not new. It's not rocket science," says Coun. Joe Cressy, a proponent of the approach.

Cressy notes his own uncle has lived in a west-end supportive housing complex for many years, allowing him to live independently with access to mental health supports. "He has lived courageously with schizophrenia since he was a young man," he says.

"He's now nearly 70."

Right now, it's not clear just how many Toronto residents are living in supportive units, given the number of different agencies involved, though the city does administer around 10,000 of the units, according to city staff.

What is clear is the need far outweighs the supply.

17,500 households on wait list

More than 17,500 households are on the wait-list for supportive housing for people suffering from addiction and mental health problems, funded by the Ministry of Health, and city numbers show 1,800 new units are needed every year over the next decade.

The estimated operating cost for the city's proposed 600 units is close to $14 million each year, the plan notes, while capital costs are expected to range between $160 million and $213 million, which would require federal or provincial funding streams.

City staff suggest it could be worthwhile investment from a purely financial perspective, given the high cost of operating shelters: An average shelter bed costs $110 per day to operate, while an average supportive housing unit costs only around $63 per day.

Cressy warns the plan needs ongoing support to succeed; first, from council, and through ongoing investment to hit the annual targets from both the city and higher levels of government.

There's cash in place for 2020, and through a successful motion during the committee meeting on Wednesday, Bailao called for capital funding to create another 600 units in 2021 in the city's budget, while having council push the provincial and federal governments to provide the operating costs.

Another motion that also gained support, from Coun. Kristyn Wong-Tam, aims to explore how to allocate one third of the units built in Mayor John Tory's affordable housing initiative for creating supportive housing.

That program, Housing Now, aims to build thousands of affordable units on city-owned plots of land, but features minimal supportive housing.

Kira Heineck, executive lead of the Toronto Alliance to End Homelessness, says that's a key overlap that needs to be expanded to complement the city's supportive housing plan, which "doesn't produce a lot more new units," she notes. "It's creating units out of existing resources."

Even so, Heineck and other advocates hope it gains council approval.

Talia is among them, though he stresses that solving the housing problems facing Toronto is a complicated task beyond just offering supportive housing.

From tenants being evicted by landlords eager to raise the rent, to a provincial policy scrapping rent control for new units, to overflowing city shelters — there are many hurdles to overcome.

But he says the role supportive housing can increasingly play is to remove the barriers vulnerable residents face while living precariously, which can keep them in shelters indefinitely.

Without supports for issues from personal hygiene to getting treatment for addiction issues, he ponders: "How do you vote? How do you go to a doctor's appointment? How do you have a date?"

Those are questions he doesn't need to ask anymore.

"Everybody deserves a safe place," Talia says. "I was never safe before; I'm safe now."