CIA's Former Chief of Disguise Reveals Spy Secrets: 'People Who Knew Me Well Will Be Shocked' (Exclusive)

Trailblazer Jonna Mendez revolutionized the CIA’s techniques — and now she’s finally sharing her own story

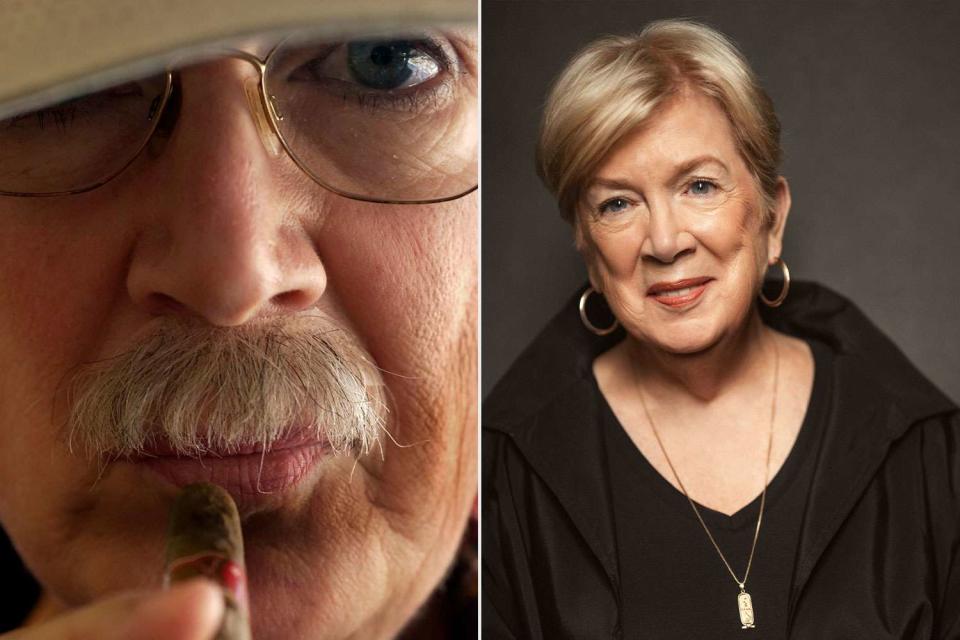

Nancy Pastor/The Washington Times; Tina Leu

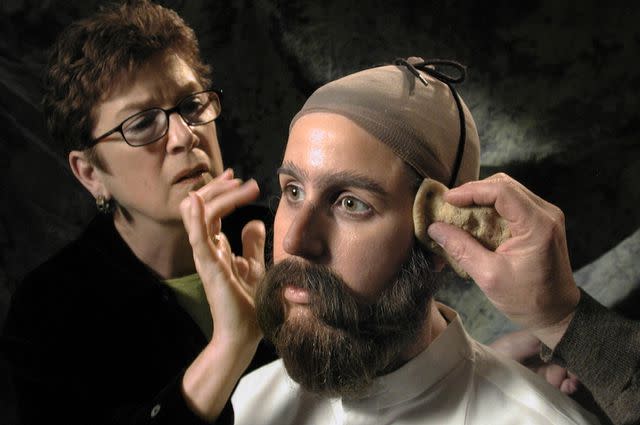

“I didn’t join the CIA thinking I’d drive over the Alps in a Jaguar like James Bond,” says Jonna Mendez (in 2023 and, opposite, disguised as a man in 2005).When Jonna Mendez, then the CIA’s chief of disguise, was asked to brief President George H.W. Bush on the agency’s new mask technology in the early 1990s, she wanted to make a powerful impression to secure more funding.

“It’s expensive to make these masks,” says Mendez, 78.

Meeting Bush in the Oval Office disguised as a Latina woman with black curly hair, she described the extraordinary results her team achieved to evade Russia’s KGB. Bush curiously glanced to her side, perhaps looking for a briefcase holding the new disguise. She told him she was wearing it.

“He said, ‘Hold on, don’t take it off yet.’ Then he got up and took a closer look,” she recalls. “He said, ‘Okay, do it.’ ”

Like a Mission: Impossible character, Mendez slowly peeled off a remarkably lifelike mask, revealing her true face: blue eyes, fair skin and short, dark blonde hair. When she held up the disguise that duped everyone in the room, Bush and his advisers seemed dazzled.

courtesy JONNA MENDEZ

“There was no question about it: He was entertained,” says Jonna Mendez (disguised to brief President George H.W. Bush in the early 1990s).“The masks were something that no one else, not even Hollywood, could do,” she says.

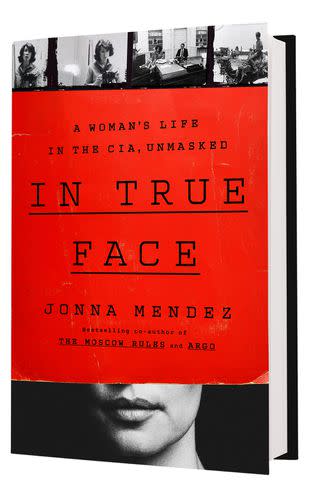

That’s just one memory from Mendez’s 27-year tenure as a master of disguise that she’s mined for her CIA-reviewed memoir In True Face: A Woman’s Life in the CIA Unmasked, out March 5.

“This is my career that no one knows about,” she tells PEOPLE in this week's issue from her Reston, Va., home. “You step into that world, and the door closes behind you. I thought it would be interesting to open the door. People who knew me well will be shocked.”

Related: Emily Hikade Left the CIA and Built a Royals-Loved Pajama Empire: 'I Owed It to My Kids' (Exclusive)

Mendez’s rise in espionage traces back to a whirlwind romance in the mid-1960s. Born Jonna Hiestand in Campbellsville, Ky., the English lit major visited Germany for a friend’s wedding at age 20 and decided to start a new life far from home. While working in Frankfurt writing correspondence for Chase Manhattan Bank’s president, Mendez met American John Goeser, who she thought worked as an Army civilian.

“I was so impressed by this sophisticated guy — very nice-looking,” she recalls.

They became engaged a year later, and Goeser confessed he worked for the CIA. If she married him, their lives would be full of secrets.

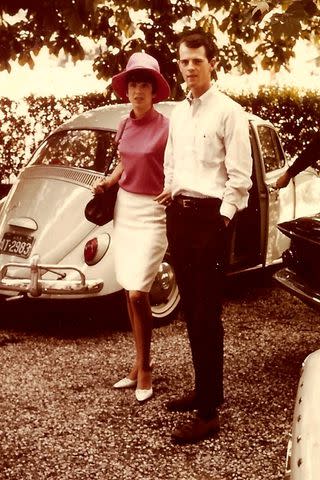

courtesy JONNA MENDEZ

“I was excited for what lay ahead,” Jonna says Mendez (before her honeymoon with first husband John Goeser in 1967).“Sounded like the adventure of a lifetime,” she writes in her book. “I wasn’t wrong about that.”

Mrs. Goeser became a CIA secretary, then known as a “contract wife,” but eventually told her boss she was bored. He suggested she take clandestine photo courses to learn how to gather intelligence.

For more on Jonna Mendez, pick up the latest issue of PEOPLE, on newsstands Friday, or subscribe here.

“My whole career turned,” says Mendez, who excelled in photography and, after soaking up her colleagues’ expertise, masterminded critical disguise operations in the Cold War’s most hostile locations, from Moscow to Havana to Beijing.

“We developed innovative disguises to instantly change appearances, created concealed cameras and equipped CIA operatives and foreign assets,” she says. “We were able to monitor Russians to stay abreast of Russia’s progress in the nuclear realm.”

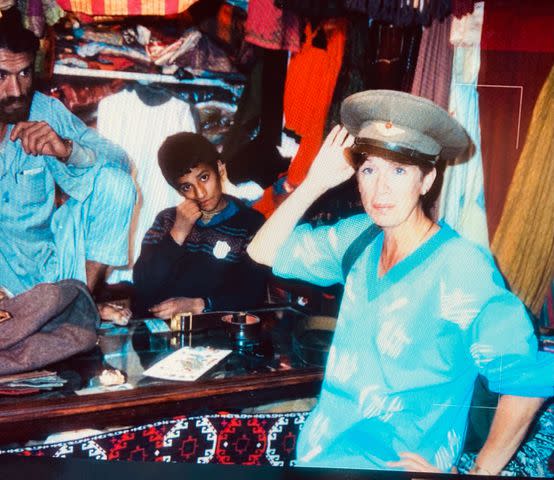

courtesy JONNA MENDEZ

“We were looking at possible exfiltration routes” for a defector, says Jonna Mendez (in Pakistan in the late 1980s)But Mendez discovered U.S. enemies weren’t her only problem. As she ascended the CIA’s ranks, she experienced toxic masculinity in a field where women were overlooked.

“You have to be not as good as men are—you need to be better,” she says.

Once, a resentful male colleague rolled a defused grenade at her. It went off several feet away.

“I started shaking,” she says. “I thought, ‘He wants me to act like a girl,’ so I didn’t. I didn’t cry.”

Courtesy Jeni Novak

Jonna Mendez (trying on looks) says, “There’s a satisfaction knowing it’s body armor.”Another time, a boss refused to let her see instructions from headquarters for a complex and dangerous mission, and mischaracterized her disguise assignment as photography. Without her usual materials in a country she’s not at liberty to name, Mendez needed to alter a foreign asset’s appearance on the fly. Her resourcefulness saved them.

“I wanted to make the asset look older, and I used Dr. Scholl’s foot powder to give him gray hair,” she says. “The operation was successful and the most significant I was ever involved in.”

She found the ally of a lifetime in Antonio “Tony” Mendez, a charismatic CIA officer and former chief of disguise best known for rescuing six U.S. diplomats from Tehran in 1980. Ben Affleck portrayed him in the 2012 Academy Award-winning film Argo. At the height of the Cold War she and Tony teamed up to help pioneer an arsenal of brilliant evasion protocols and James Bond-worthy gadgets.

“We were Q,” Mendez says, comparing their office of scientists and artists to the techno-gurus in the 007 movies.

Their groundbreaking tactics enabled CIA officers to outfox the KGB in Moscow.

“We could make anything—quick-change license plates, jacket buttons that were compasses, silk jacket linings that could be maps,” she says. “We put bugs in books. We put cameras in cigarette packs, strap-on pregnancy bellies—we put them everywhere.”

In 1990 Mendez’s 23-year marriage to Goeser ended amicably, and in 1991 she married Tony, who had recently retired from the CIA and begun pursuing his love of painting. The couple lived on their farm in Washington County, Md., and she continued her undercover work at the agency.

courtesy JONNA MENDEZ

Jonna Mendez says husband Tony (at the 2013 Academy Awards for Argo, in which he was played by Ben Affleck) was her “life raft."“Then I got pregnant—at 47,” says Mendez, who gave birth to their son Jesse in 1993 and soon retired from the CIA.

“I thought spy stuff would recede into the background,” she says. “I had this vision of how that mom thing would play out.”

But the Mendezes partnered on bestselling books about their clandestine life — including Spy Dust, Argo and The Moscow Rules — before Tony died from complications of Parkinson’s disease in 2019.

Courtesy the International Spy Museum

Jonna Mendez (left, giving a tutorial at the International Spy Museum in 2002) says the center “isn’t just a project— it’s become a family.”“We had a bond like I’d never known. Losing him was exquisitely painful,” she says. “He was my other half. I’m still not over it.”

These days, as she finally shares her own story, she’s reminded of their achievements when she roams the halls of the International Spy Museum in Washington, D.C., where her Bush-era mask and that lifesaving can of foot powder are displayed. Now a museum board member and lecturer, she hopes to inspire a new generation to serve.

“At the CIA, if you have a great idea, you can get it to the President,” Mendez says. “That felt like a special power, because we knew that there always was the opportunity to save the world."

For more People news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on People.