What is cloud seeding? How scientists hope to generate rain

Clouds floating over withered crops and desiccated soil hold millions of tonnes of water that could nourish the land and replenish our wells.

What if humans could force those clouds to produce rain over areas that desperately need a refreshing drink?

Inventors and researchers have spent decades searching for the answer, leading some to dabble in a theory known as cloud seeding. Here’s a look at how the process works and why the experiments are a mixed bag when it comes to success.

DON'T MISS: Is hacking the atmosphere a 'cool' idea to offset global warming?

Clouds and rain are built on specks of dust

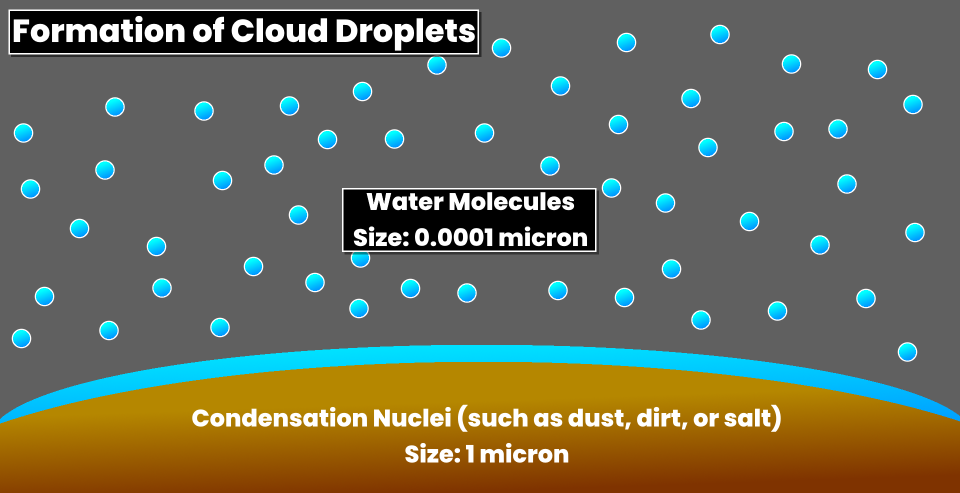

Clouds don’t form out of thin air. Water vapour floating through the air can only condense or freeze when it finds a surface to cling to—usually specks of dust or salt suspended high in the atmosphere.

Moisture clings to these particles and creates ice crystals or water droplets, forming the building blocks for clouds as mammoth as a cumulonimbus and as delicate as a wispy cirrus.

Precipitation forms when rising air forces these cloud droplets to collide together. The new droplets grow with every collision until they’re too heavy to remain suspended and fall to the ground.

Cloud seeding seeks to jumpstart that process

The theory of cloud seeding relies on the process of artificially forcing cloud droplets to grow until they fall as precipitation.

Researchers have had varying levels of success in seeding clouds with materials such as dry ice or tiny particles known as silver iodide—both of which can kick-start the process needed to grow cloud droplets.

By introducing these particles into clouds, scientists hope to force cloud droplets to grow and merge to the point that they develop precipitation.

Teams attempting to create precipitation have used innovative methods to introduce particles into the clouds, including small airplanes, cannons, and even tiny rockets.

Public and private research programs around the world have tested cloud seeding as a cure for droughts and wildfires. Some groups, like the Alberta Severe Weather Management Society, even research cloud seeding in an effort to reduce the size of hailstones that could cause costly damage.

The Associated Press reported in 2023 that the U.S. federal government awarded the Southern Nevada Water Authority more than $2 million to pursue cloud seeding in an ongoing effort to alleviate the region’s intense water stress.

Nevada’s budding effort joins several other similar programs in the western U.S., including an established cloud seeding program in Colorado that’s been running for more than 70 years.

WATCH: These pilots fly directly into storms to reduce its damage

Cloud seeding’s effectiveness is up for debate

Cloud seeding exists in theory and in practice. But does it really work? Studies are mixed on the effectiveness of cloud seeding in different environments.

One problem is that it’s difficult to determine whether clouds are going to produce rain anyway. Did it rain because it was always going to rain, or did it rain because of cloud seeding efforts? It’s a sticking point that scientists are still hoping to resolve.

Another issue is that researchers have found that the practice is more productive in certain environments.

The crew of Project Stormfury poses for a photo in front of a U.S. Weather Bureau plane used for the program, ca. 1966. (NOAA Photo Library)

A well-known program carried out by NOAA in the middle of the 20th century sought to decrease the intensity of hurricanes by seeding the storm’s eyewall. The theory behind Project Stormfury held that cloud seeding might disrupt the internal structure and force a hurricane to weaken.

Researchers nixed the program after it became clear that cloud seeding was ineffective for the warm rainfall process that occurs within hurricanes, and the fact that these storms frequently replace their eyewalls anyway.

RELATED: Cloud seeders used to reduce size of Alberta's hail

A recent study released by the University of Colorado Boulder found that cloud seeding is more effective for snow than it is for rain in warmer environments. That may help mountainous areas, but it may not bode well for warmer climates gripped by drought.

It’s also difficult to determine just how much precipitation is produced as a direct result of cloud seeding. This issue looms large over the practice, especially as drought-stricken communities allocate funds for cloud seeding programs.

However, the Colorado scientists’ snow study did produce a statistic on the matter. Researchers claim that three cloud-seeded snowfall events produced “a total of about 282 Olympic-sized swimming pools worth of water,” according to the university’s press release.

Weather modification is controversial

The implementation, benefits, and consequences of weather modification remain a highly controversial topic around the world, made worse by a deluge of misinformation that proliferates on social media.

Most methods of geoengineering floated for debate are purely hypothetical or flat-out conspiracy theories. There are few practical ways to directly attempt to influence the weather.

A recent report by The Weather Network’s Nathan Howes on curbing the effects of climate change by drying the Earth’s stratosphere highlights the sheer difficulty of weather modification, along with the potential downsides to such activities.

Some scientists warn that cloud seeding could have unintended consequences, as well.

Dr. Laura Kuhl, an associate professor at Northeastern University who specializes in climate and public policy, outlined some of the potential pitfalls of cloud seeding in an article published in The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

A view from a U.S. Weather Bureau plane during a cloud seeding mission in September 1969. (NOAA Photo Library)

“While cloud seeding is often described as ‘creating’ rain,” Kuhl wrote, “it can be more accurately described as moving rain from one location to another, and cloud seeding may simply redistribute risk.”

She added that the practice of cloud seeding may raise “large governance questions about how to ethically divide water and who controls the sky,” as well as environmental concerns about the toxicity of silver iodide used in the practice.

Header image courtesy of NOAA. Contains files from the Associated Press and The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.