Code grey: Inside a 'catastrophic' IT failure at the Queensway Carleton Hospital

Emergency room doctors, nurses and other health-care professionals who worked through the night during a major, hospital-wide computer and phone outage in Ottawa were "sticking their necks out" in an "exceptionally unsafe" environment, according to documents obtained by CBC News.

Inaccessible medical records, inoperable equipment, defective backup phones and pagers, and poor communication from administrators plagued the Queensway Carleton Hospital (QCH) for nearly 20 hours in early September when a "code grey" was declared, internal records obtained through a Freedom of Information request show.

Code grey refers to infrastructure failure. QCH called one shortly after noon on Friday, Sept. 9, which lasted till 9:38 a.m. the following day.

According to QCH executives, a one-two punch of computer hardware failures — first the primary core, then the backup core — affected everything from medical devices to phones.

"This is the worst-case scenario," a hospital vice president concluded in a memo.

In the hours following QCH's lifting of code grey, several doctors expressed anger and frustration over how the crisis was handled.

"I'm very disappointed that we were asked to keep seeing new patients when our department and the hospital had a severe/catastrophic code grey," one physician wrote in an email to hospital leaders.

"Our ED (emergency department) should have been closed to allow us to take care of admitted and existing patients in our department … Once again I shake my head at the fact that our collective voice in our hospital isn't valued."

The cause of the outage has yet to be revealed. In a subsequent statement to CBC, a hospital spokesperson said the age of equipment may have played a role, and the parts in question have since been replaced.

"It was a very difficult 20-hour period, compounded by the significant staffing shortages and fatigue that the team has been experiencing after 2.5 years of pandemic response," the statement read.

Patient and privacy concerns

Internal emails and notes exchanged between staff show doctors had to, at times, find unconventional and possibly unethical ways to overcome equipment challenges.

"There was no access to reports to CT scans. We had a nighthawk [radiologist] from Alberta and we had to use our cellular phone coverage to ask for imaging and get reports. Possibly broke a few health privacy rules there so we could help patients," the doctor wrote in a post-mortem email.

At least four physicians expressed dismay over the "catastrophic event," according to the records. CBC is not identifying the four individuals because they were clearly complaining internally.

According to staff meeting notes, questions were also raised about patient confidentiality around "providing critical lab results by radio" during the outage.

The hospital's chief privacy officer, Tim Pemberton, acknowledged "it is not ideal but the best we can do under these circumstances to ensure both privacy and patient safety," the minutes from Sept. 9 read.

In its subsequent statement to CBC, QCH said "there were no patient safety incidents reported that caused harm, nor privacy violations."

Chaotic scramble for backups

During the early hours of the code grey crisis when most phones, internet and IT systems were down, staff scrambled to notify each other and find alternative ways to communicate.

"We are currently experiencing issues that seem to be related to our network," QCH's head of information technology services, Karen McMullen, wrote in an all-staff note.

The emergency department was already full when the code grey was declared, but with none of the doctors able to fully access data on patients or send medical orders, staff rushed to distribute backup pagers and radios across the various departments.

The hospital also delegated "manual runners" to help pass hand-written notes.

Patients' call bells and bed alarms were disconnected from the wireless phones that nurses normally use to respond to them. In response, nurses were told to personally check up on each patient every 15 minutes and rely on "visual call bell noise and flashing light" in the hallway.

"Do you guys have any spare cell phones down there?" wrote one staff member in a message typical of the early emails sent from an iPhone.

According to the hospital's IT department, the network outage was caused by a "core hardware failure." A statement from the hospital noted a "software bug" further impeded the backup system that was supposed to kick in and it did not work accordingly.

"Hopefully we will be back online in a couple of hours," McMullen wrote mid-afternoon, after the code grey had been announced.

But it would take another 17 hours before McMullen's department gave the "all clear."

Emergency department stayed open

As the night approached, hospital leaders were faced with another dilemma — whether or not to keep the emergency department (ED) open.

Ambulances were redirected to The Ottawa Hospital during the day, but the executive team at QCH chose to keep the ED open through the night, despite calls from physicians to do the opposite.

By supper hour, a physician was placed in the triage area to assess patients.

"There was an ask to close the ED," Yvonne Wilson, vice-president of patient care would later reveal in an email dated Sept. 10.

"We balanced the risks of closing access to emergency care for our patients, the ability of the other three hospitals [to] absorb these patients and the impact on EMS to provide service to our community against our providers being able to provide care with delays in imaging, results of labs and utilizing downtime procedures. These factors helped to form our decision to keep our ED open."

Wilson sent the explanation in response to a chain of complaints from doctors after the fact.

In one email, a doctor who worked the overnight shift said he felt "very uncomfortable" with the lack of access to phones, health-care software and patient reports.

"EMS had an EMS medic holding the fort for some of their off loads," he wrote. "The ambulances seem to have no longer received the memo and started pouring back in around 11 p.m."

According to meeting minutes, during the peak of the night, nine ambulances were dropping off patients, which "challenged" the ED.

"They remained for many hours," the point-form notes read.

The Ottawa Paramedic Service said it experienced four hours of "level zero" on the evening of Sept. 9 — ambulances were maxed out from 5 p.m. to midnight.

"The decision by QCH to keep its emergency department open during the outage helped to ensure patients across Ottawa could access timely care that evening," said Pierre Poirier, chief of paramedic services.

But another doctor said he "100 per cent" agreed that the hospital "should have closed the ER."

"Anyone working that evening was sticking their necks out medicolegally, trying to practise medicine with all the restrictions … detailed," he wrote, referring to his and his colleague's medical and legal concerns.

"I had to send a patient to [The Ottawa Hospital] emergency room as I told him point blank, 'I cannot provide adequate care to you here in our ER in the state we're in.'"

I told him point blank, 'I cannot provide adequate care to you here in our ER in the state we're in.' - QCH doctor during code grey

The doctor explained the patient he turned away overnight had come in with shortness of breath and other respiratory issues three months following a lung transplant.

He said he was unable to help the patient because he had "no ability to access any of his records, or previous imaging."

When asked about its decision to keep the ER open, QCH told CBC it had "no choice but to stay open."

"It was more [out] of necessity than a decision. Unfortunately, it is the front-line team that carries the burden," the statement read.

'Squinting' at single, tiny screen

According to the various meeting minutes, sometime at night, hospital staff found a way to use an old monitor to view CT scans.

"There is a station set up in CT and the ED physicians are to come to view the images," the internal notes read, adding the monitor was connected to a single console.

Based on subsequent complaints from doctors, it appears the monitor was also used to view X-ray results.

"It was communicated to us that the radiologist on call would not be able to provide readings for our department for unclear reasons," a doctor wrote.

"I believe the communication was that they were not comfortable reading images on that small monitor as it did not provide adequate resolution."

The doctor said it fell upon him to interpret the X-ray scan by "squinting at the tiny screen."

"Why is the expectation we continue to provide care in a substandard environment, but our consultants do not receive the same marching orders?" the doctor wrote in reference to the radiologist on call, adding he did not feel it was an "all hands on deck" way of dealing with the crisis.

In its subsequent statement to CBC, QCH disputed the description of the makeshift monitor.

"We added a high-definition monitor to our CT scanner," the statement said. "It allowed for the viewing of images, but not the additional radiologist tool sets."

In one notable internal email, a doctor said he had to rely on his basic skills and instincts to treat patients — making a comparison to working in the 19th century.

"Look, I'm happy to work like William Osler and use my stethoscope and my clinical acumen," he wrote, referring to the legendary Canadian physician and one of the founding professors of the Johns Hopkins Hospital.

"However, these issues are not new and … we seem to have become a department that is asked to keep calm and carry on," the doctor concluded.

As the night wore on, some hospital staff were able to access parts of the network system.

However, during the final technical update just past midnight, hospital leadership made a decision to wait until the morning to call off code grey.

Though staff would not be given the "all clear" till after 9:00 a.m., people in various departments were encouraged to resume using some software and find other workaround solutions.

Medication orders, for example, were written in pink paper copies, and sent to a third-party telepharmacy company for processing.

Scant social media posts

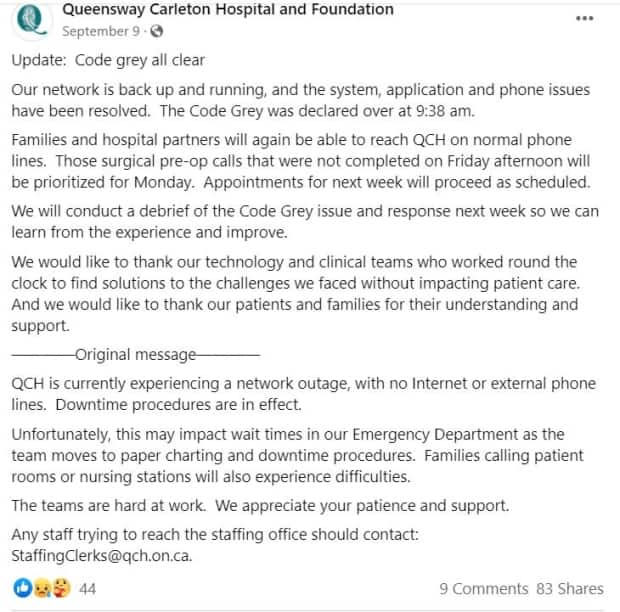

Throughout the night, QCH provided very little information to the public, announcing on social media that a network outage "may impact wait times in our emergency department as the team moves to paper charting and downtime procedures."

"Families calling patient rooms or nursing stations will also experience difficulties," the post stated.

In an email sent to QCH leaders in the morning, one doctor criticized the communication strategy.

"I think this significantly buries the lede in terms of the impact and ability for our hospital to provide care," he wrote.

"Moreover, there was no notification about the code grey that I could see in our front doors. I imagine most people seeking care in our ER don't check Facebook before coming in."

The doctor said the hospital had a responsibility to communicate to the public what level of service it was able to provide so patients could make an informed decision.

"If my dad was headed to an ER that has a sign out front saying, 'we can't access any of your medical records, or look at your scans, and blood work will take four hours,' I'd tell him to go elsewhere," the doctor wrote.

In its subsequent statement to CBC, QCH said it would normally post "downtime signs" in the emergency department. However, they were "discovered to be missing."

"They were since reprinted and are in ED for when they are next needed," QCH said.

More than once, the official statement blamed the pandemic for exacerbating an already stressful situation.

"Our health-care system is fragile. This makes each new compounding issue — like a network outage — more complex … This takes a heavy toll on our front-line team," the statement said.

"When clinicians sound alarm bells, we understand," QCH added. "We all want to fix this system."