Country Music and Música Mexicana Share a Deep History Worth Remembering

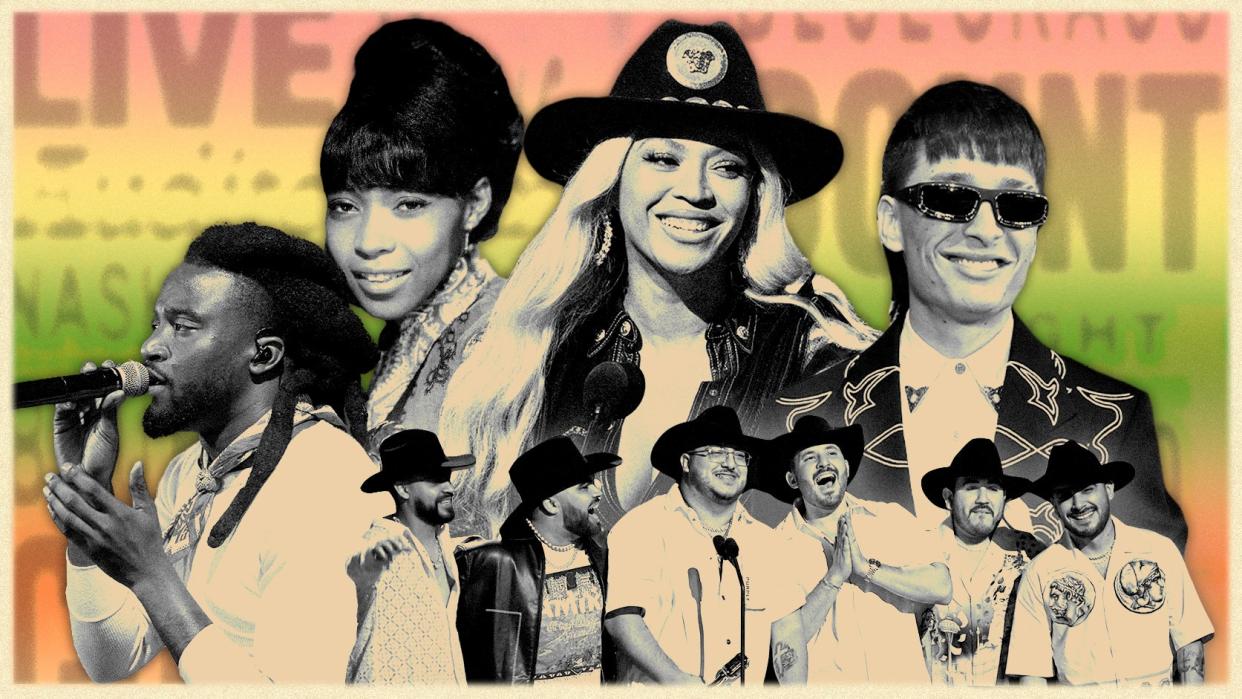

Composite. Courtesy of Getty Images/Treatment by Liz Coulbourn

If America’s sense of national identity has a soundtrack, surely the sound is Country Music — a commercial genre borne of the myth-making it took to forge America itself: a yarn spun from the threads of the inherent nobility of the American cowboy, the glamorization of westward expansion, and a nascent militaristic patriotism that would go on to define the contours of a rising global power.

But the time is ripe for the myth to be reexamined and lies to be unfurled; in a cultural moment when Beyoncé has complicated the country music narrative in the wake of the release of her latest effort, Cowboy Carter, and the rise of Música Mexicana on the global stage has taken hold, it’s evident the contours of the genre are, like its country’s borders, mutable and porous. Shifting throughout history. Excluding some and including others. And like many myths, the premise rests on erasure: of Native American genocide, of African American slavery, of Black musicians’ foundational contributions in music and artmaking, of the Mexican roots of the country music sound.

The rigid walls of country music are beginning to erode — but before the world envisions an all-embracing future of country music, recognizing its true history has never been more vital.

“The existence of a border means it has to be maintained,” Dallas-based music journalist Taylor Crumpton tells Teen Vogue. “And country music loves a border, because it has to maintain a sense of white American purity. Country music has also been used as a ploy to promote an idea of American patriotism which is relying upon, dependent on the military industrial complex.”

Mississippi State University history professor Joseph M. Thompson argues in his book Cold War Country: How Nashville’s Music Row and the Pentagon Created the Sound of American Patriotism that at the conclusion of WWII, as US military installations cropped up across Europe, the Pacific and Caribbean, the Armed Forces Radio Service expanded the reach of of American popular culture far beyond its borders — and as the Cold War took hold, big band jazz and crooners gave way to country music programming. Soon enough the Pentagon recognized country music’s potential to not only cater to servicemen’s tastes, but also to entice potential recruits — from rural, disenfranchised white communities in the South. Likewise, the nascent, more formalized country music industry forming in Nashville saw the potential of tapping into a global market.

“The country industry located along Nashville’s Music Row generally followed this political trajectory toward conservatism, not because of some inherent ideology within its artists and fans but because of the lucrative partnerships it had established with the Pentagon during the Cold War consensus of the 1950s,” Thompson writes. Cold War defense policies increased demand for more soldiers. More soldiers meant steady pay, government benefits, and jobs in the civilian sector. Soldiers bought more country records and requested more country music on military radio across the world. “Simply put, the Cold War was good for the country music business.”

The mental gymnastics required in order to carry across this mythology of a benevolent and homogenous Americana identity globally is worth parsing. “Because country music has always aligned itself with those forces of state and violence and harm that has inflected generational trauma and harm on African Americans, Indigenous Americans, and Mexican Americans, they cannot have a myth or a lore that is multiracial in nature, because that contradicts the purity," Crumpton says. “If I'm bringing this banjo [with me] to inflict harm against people of color abroad I can't let you know that this instrument is African and Indigenous and Mexican right? It needs to be white and country.”

“I think people forget that the blues circuit existed before the chitlin circuit and these circuits never had borders," Crumpton continues. "These circuits were fluid; they were going from place to place, city to city, country to country – United States, Mexico, St. Louis, New Orleans… that doesn't fit a white racial pure narrative of country music. Country music needs to be Nashville. It can't be Mexico, New Orleans, St. Louis, Texas.”

The truth of country music’s multitude of seminal influences: in blues of New Orleans, in ranchera, conjuntos and corridos from Mexico, of even the polkas of German immigrants, is part of the fabric of the genre.

The Country Music Hall of Fame, founded in 1961, currently has 146 members. In 2000, Charley Pride became the first African American to be inducted. To date, there are no Latino members.

“I think that's the tension that's coming up today,” Crumpton says. “I think we've respectfully hit a point where folks are tired of being lied to about their traditions and being lied to about who is worthy and deserving to be an American and who is not. My friends who live on the border always say the border crossed me, I didn't cross the border.”

Still, the shifting tides of contemporary country music culture, its definitions, its rising stars — who is allowed within its borders and who is kept out — are increasingly challenging to pin down. “I’m honored to introduce so many people to the roots of so many genres. I’m so thrilled that my fans trusted me,” Beyoncé recently told The Hollywood Reporter. “The music industry gatekeepers are not happy about the idea of bending genres, especially coming from a Black artist and definitely not a woman.”

Grupo Frontera, a Tejano band from South Texas, is one group whose star is rising to astronomical heights. Playing guitar and accordion-driven traditional ranchera music (a seminal root of country music) at parties around their hometown of Edinburg, Texas, the group pushed past the local party scene at a feverish pace, capitalizing on a hunger for authentic representation on a wider scale and eventually making it to the Coachella fairgrounds and collaborations with titans like Bad Bunny. It’s no secret why the group has become fuel for a movement of northern Mexican regional music dominating both Latin charts and so-called mainstream music.

One of their contemporaries, the provocative Peso Pluma, has taken a different approach to music domination — rising at breakneck speed from from TikTok buzz to the Coachella main stage and becoming Billboard chart neighbors with Taylor Swift and Drake. He crafted a foundational mythology for himself singing narcocorridos (contemporary ballads that take the folk hero genre of corridos, and make anti-heroes out of drug lords). While he’s largely set aside those themes, his mythos is largely tied to the flavor of lyrical storytelling of this genre. Coincidentally, the outlaw is a foundational archetype in country music, too.

Others, with heritage from both sides of the border, chafe at notions of being pushed into one genre or another. Rising country artist Laci Kaye told the Los Angeles Times: “Because my mom is Hispanic and I have a little bit of Mexican in me, there were talks of doing this Latino country thing, and I was just not on board because I felt like I was taking a spot — I mean, look at me — that somebody else could very much take.”

Her words echo conversations that have been taking place for decades, from Linda Ronstadt’s straddling of genre and identity, to Freddy Fender’s success as a country artist after changing his name from Baldemar Huerta and abandoning Latin music chart-topping success. The genre, and notions of self, have asked artists to choose: this or that. It’s a question Beyoncé wrestles with as well, through the seams of Cowboy Carter.

“I think it's a beautiful thing to witness not only a person evolve over time but a genre evolve over time and for anyone who may be curious about genealogy or ancestry,” Crumpton says. “A lot of young people as of late have become very much focused on ancestral veneration and reverence and one of the ways in which you can do that is [through] music because blues music, and Mexican folk music, and country music, they're telling stories of where people have been, stories of people now, even things in the future.”

Crumpton considers Beyoncé’s effort on Cowboy Carter through an Afrofuturistic lens: how can modern technology be used as a tool of historical liberation, on an album where you have Linda Martell on the same project with Tanner Adell and Brittney Spencer? “We can make a parallel to Black studies and Mexican studies and Caribbean studies and how young people brought that through organizing in institutions, they can do the same with country music.”

Rising artist Shaboozey is yet another of those beacons shining into the future of country music, recently releasing his third album Where I’ve Been, Isn’t Where I’m Going after a career-boosting feature on Cowboy Carter. Despite the staggering popularity of his music, which he calls “music for the modern cowboy,” he still rests somewhere on the fringes of the mainstream genre. “In Nashville, that’s who me and my friends are: We’re the rebels, the outlaws, the outliers,” he told Harper’s Bazaar. “So seeing my success and the success of my friends, we’re happy to be a part of this more alternative community, because we’ll always support each other.”

In a recent conversation between Rihannon Giddens and Brittney Spencer in Harper's Bazaar, Giddens said, “I think we have a big opportunity right now to do something with this community that’s coming along and this focus on the history and on the responsibility that we have to the people who came before us…we’ve got to turn this moment into a movement, into systemic change.”

But what would it take for lasting change in country music? For its borders to remain flexible and ultimately more accepting? For Crumpton, it means staying with and investing in country music in an ongoing way.

“[Country is] an institution that's very firm, rigid and fixed,” she says. “If you do not abolish it, then we're going to continue to have the same conversations about like racial inequity and revisionism in country music because Nashville and Music Row will try its best to wait this out and for people to forget.”

Originally Appeared on Teen Vogue

Want more great Culture stories from Teen Vogue? Check these out:

A New Generation of Pretty Little Liars Takes on the Horrors of Being a Teenage Girl

Underneath Chappell Roan’s Hannah Montana Wig? A Pop Star for the Ages

Donald Glover’s Swarm Is Another Piece of Fandom Media That Dehumanizes Black Women

On Velma, Mindy Kaling, and Whether Brown Girls Can Ever Like Ourselves on TV

Gaten Matarazzo Talks Spoilers, Dustin Henderson, and Growing Up on Stranger Things

How K-pop Stars Are Leading Mental Health Conversations for AAPI People and Beyond

Meet the Collective of Philly TikTokers Making You Shake Your Hips

The Midnight Club Star Ruth Codd Isn’t Defined By Her Disability