Courts set high bar for conviction on dangerous driving causing death

On Nov. 2, when Superior Court Justice Catherine Aitken pronounced Deinsberg St-Hilaire not guilty of dangerous driving causing death and leaving the scene of a fatal collision, Kerry Nevin stood up and stormed out of the courtroom.

"This is a disgrace," Nevin shouted before the door swung closed behind him.

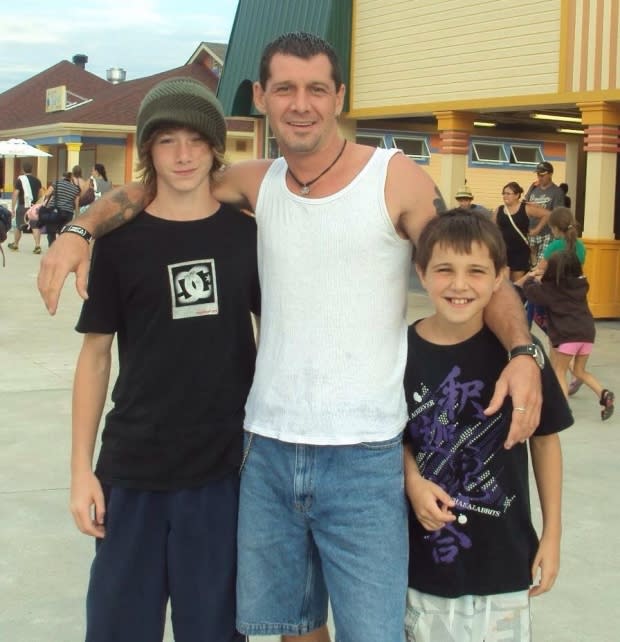

Early on the morning of June 28, 2015, Nevin's son, 39-year-old Andy Nevin, was riding his bicycle along Leitrim Road in south Ottawa when he was struck and killed by a vehicle. St-Hilaire was behind the wheel. He later said he'd fallen asleep and woken to a bang.

The cyclist was hurled into a ditch, so when St-Hilaire checked his rearview mirror he saw nothing in the road behind him. He assumed he'd struck a roadside mailbox and kept driving.

Outside the courthouse, Nevin's family voiced more anger over the acquittal.

"We are teaching society that as long as you say you fell asleep you can get away with killing someone," said Nadia Robinson, the mother of Andy Nevin's two sons. "Our justice system failed us today. It's sickening."

High bar for conviction

The charge of dangerous driving causing death carries with it a high bar for conviction. The Crown must prove the accused's driving was "a marked departure from the manner in which a reasonably prudent person would drive under the circumstances."

The Crown must present evidence of a pattern of dangerous driving leading to the collision, not just a momentary lapse in attention.

That principle was established In 2008, when the Supreme Court made a landmark ruling on dangerous driving causing death.

The case involved Justin Ronald Beatty, who drove veered into oncoming traffic on a clear, sunny day, killing three occupants of another vehicle. Beatty later reasoned he must have lost consciousness due to heat stroke.

The Supreme Court upheld the trial judge's acquittal, arguing Beatty's momentary lapse of attention didn't qualify as dangerous driving because a reasonable person in the same situation could not have acted to prevent the harm.

Referred to 2008 case

In her decision, Aitken referred to that 2008 case, ruling there was reasonable doubt of a marked departure of behaviour on St-Hilaire's part.

Aitkin also noted the lack of eyewitnesses or traffic cameras showing St-Hilaire's driving was erratic. Instead, she accepted his testimony that he'd fallen asleep at the wheel, was awoken by a bang and had no other indication that he'd hit a cyclist.

"Despite the horrible and tragic consequences of this case I am left with a reasonable doubt as to whether Mr. St-Hilaire's brief period of lapsed attention — possibly only a few seconds — was sufficient to find criminal liability for dangerous driving," Aitkin concluded.

'I think it's become part of the law we feel we can turn a blind eye to.' - Patrick Brown, Bike Law Canada

The decision disturbed civil litigator Patrick Brown of Bike Law Canada, a group that advocates for legal reform to prevent cyclists from being injured and killed.

"At the end of the day, most people would perceive staying up all night and speeding like that as a marked departure from what a normal person would do," Brown said.

Aitken did acknowledge that St-Hilaire was driving 30 km/h over the speed limit, but reasoned that was normal behaviour given the hour and relatively remote location.

But Brown believes the ruling speaks to a wider problem.

"It's concerning that to be 30 kilometres over the speed limit seems to be something we're considering an acceptable standard," he said. "It's a car culture, and I think it's become part of the law we feel we can turn a blind eye to."

'A pure accident'

Criminal defence lawyer James Foord wouldn't comment on the specifics of the St-Hilaire case, but acknowledged the tremendous pain the ruling has caused the Nevin family.

"Sometimes it's just a pure accident, and that's not a lot of solace to someone who has lost someone. But reasonable doubt is the golden thread that keeps our justice system integral," he said.

Despite his acquittal on the two charges, St-Hilaire still faces serious consequences: he pleaded guilty to obstruction of justice, a charge that could earn him up to 10 years in prison. He's scheduled back in court in January for sentencing.

The Crown has not indicated to CBC whether it plans to appeal St-Hilaire's acquittal.