Covid-19 restrictions are shattering Argentina's short-lived political truce

Until recently, Argentina’s protracted coronavirus lockdown was marked by an unusual degree of harmony, as the country’s perennially squabbling political factions came together to contain the spread of Covid-19.

But after nearly four months of consecutive lockdowns, rifts have begun to appear in that uneasy truce amid growing demands for a relaxation of quarantine measures.

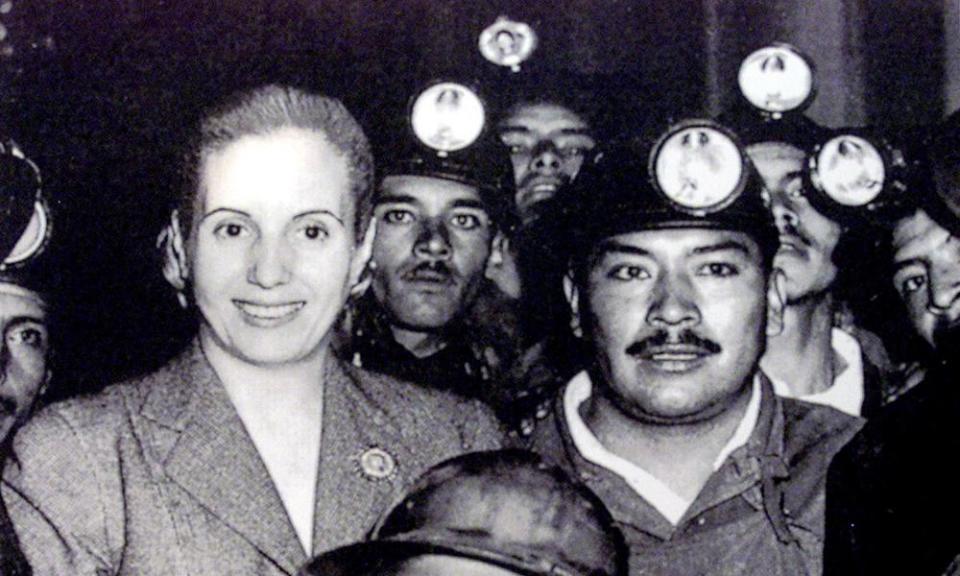

With new cases spiralling out of control, the old political rivalries between followers and detractors of the late three-time president Juan Perón, and his wife Evita, has returned to the fore.

Related: ‘You can’t recover from death’: Argentina’s Covid-19 response the opposite of Brazil’s

On one side, the Perónist administration of the president, Alberto Fernández, is struggling to keep its coronavirus lockdown in place after Argentina passed the 100,000 cases on Sunday – a four-fold increase from a month ago. On the other, an increasingly rebellious opposition and a defiant grassroots movement have been pressing for the end of quarantine rules.

The president has expressed concern at the growing acrimony over Argentina’s lockdown. “No society fulfils its destiny among insults and division, with hate as the common denominator,” he said on Thursday in an address marking Argentina’s national independence holiday.

While Fernández spoke, thousands of Argentinians were taking to the streets in a nationwide protest that mixed simmering discontent over the long lockdown with anger against his Perónist administration.

Anti-lockdown sentiment is being stoked by Fernández’s predecessor, Mauricio Macri, a pro-business politician who lost his bid for re-election last year.

“We have seen a government that has tried during the pandemic to undermine freedom of expression, justice, independence of the branches of government and private property,” Macri said in a video posted on Twitter last week. “This has generated an active and strong reaction from society, which has mobilised to express itself against these actions.”

Macri’s followers are displeased with a proposed one-time wealth tax to finance the cost of the pandemic, plans to expropriate the huge – but failing – grain trader Vicentin and the recent release, pending trial, of businessman Lázaro Báez and former economy minister Amado Boudou, both facing charges of corruption during the 2007 to 2015 presidency of the current vice-president, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner.

“They are letting them walk free while we are under house arrest,” one protester told a television reporter in reference to the lockdown. Others carried banners that read: “Don’t let face masks silence democracy.”

The political divide is mirrored by the sharp disparity between the incidence of coronavirus in the Buenos Aires metropolitan area – still in hard lockdown with 95% of the country’s active cases – and the rest of Argentina, where containment of the virus has permitted the relaxation of restrictions.

“Argentina has two realities,” health strategies under-secretary Alejandro Costa told the Guardian. “One is most of the country – where transmission has been brought under control – and the other is the Buenos Aires metropolitan area.”

The metropolitan area consists of Argentina’s capital, Buenos Aires, a bastion of anti-Perónist sentiment governed by Macri’s Republican Proposal party for the last 13 years, with 3 million inhabitants – and its surrounding urban sprawl, known as Greater Buenos Aires, the backbone of Perónist support, with 11.8 million inhabitants, which falls under the jurisdiction of the province of Buenos Aires.

“They are two separate but indivisible districts,” said Costa.

The pandemic has forced the city’s chief of government, Horacio Rodríguez Larreta, from Macri’s more conservative party, and Buenos Aires governor, Axel Kicillof, a Perónist firebrand, to coordinate health policies. But their uneasy cooperation, mediated by even-keeled president Fernández, is being tested by Larreta’s eagerness to ease the lockdown.

Buenos Aires is planning a gradual reopening starting on Friday, despite reporting the highest incidence of coronavirus in Argentina. More than 38,000 city dwellers have tested positive so far – an average of three people per city block.

Related: Argentina cordons off virus-hit slum as critics decry 'ghettoes for poor people'

Governor Kicillof is fearful the high level of contagion could spread to his province, where cases are numerically higher but proportionally much lower. “The province has only 0.3 contagions per hundred people, the city has one contagion per hundred,” Kicillof said at a recent press conference.

Buenos Aires also leads Argentina’s mortality rate with 230 Covid-19-related deaths per million inhabitants, compared with about only 60 per million in Greater Buenos Aires and just 41 per million for all of Argentina.

Public unease with the protracted lockdown, which started on 20 March, adds fuel to the fire. “The pandemic is being politicised, not by political leaders, who are cooperating harmoniously, but at a lower level,” says Martín Barrionuevo, a Perónist senator in the legislature of the province of Corrientes.

With zero deaths and only 126 cases so far, Corrientes enjoys freedoms Buenos Aires residents can only dream of. “We can hold social gatherings of up to 10 people and restaurants are open,” says Barrionuevo.

Fearful of the spread of the pandemic, the provinces are monitoring the transport of merchandise from Buenos Aires. “We have control posts on every highway, we test every truck driver,” Raúl Jalil, the governor of the northern province of Catamarca, said.

Catamarca remained completely free of Covid-19 until earlier this month, when one infected driver slipped through the controls. With only 39 contagions and no deaths so far, Jalil is confident Catamarca can keep the outbreak contained. “We were the first province to make face masks mandatory and we were the last to get infected,” the governor said.

Argentina’s second most populous and economically powerful province, Córdoba, is home to almost 8% of the country’s 45 million population, but has had just 0.9% of nationally reported cases.

“Our situation is totally different from Buenos Aires,” said Dr Carlos Bergallo, a member of Córdoba’s coronavirus task force. “Our car manufacturing plants, Fiat, Renault, Volkswagen, are operating. Shops, restaurants and shopping malls remain open, even if with restrictions.”

Experts underline the higher population density in Buenos Aires as responsible for its predicament, but there may be other factors at play. “The response to guidelines from the people of Catamarca has been exceptional,” says Jalil. “We have a different attitude, perhaps because we are less arrogant than in the big cities.”