Critics question settlement program for banks that overcharged fees

As investors await refunds from banks and other financial institutions for hundreds of millions of dollars in excess fees, critics are questioning the process around how the unwarranted charges were dealt with by their regulator.

Scotiabank, Royal, TD, CIBC and BMO, along with others, have all come forward to disclose they accumulated a total of $354 million in excess fees or unpaid interest on mutual funds and other investments.

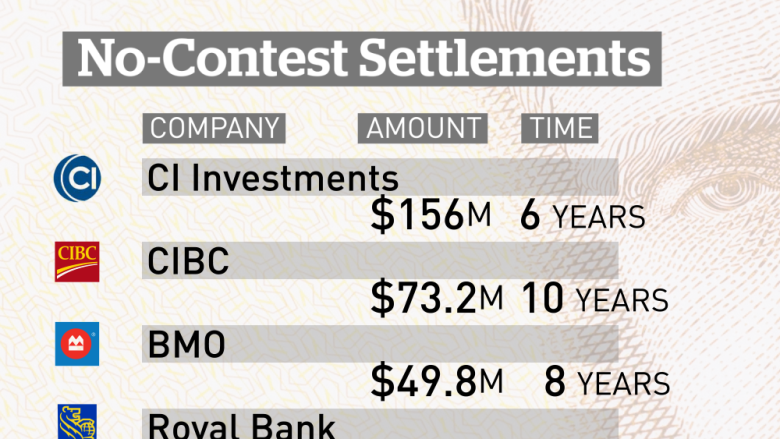

TD had been charging the excess fees for 14 years, CIBC for 10 years, while others had been charging them for six to eight years. The biggest refund came from CI Investments, which failed to pay $156 million in interest on some clients' mutual funds over a six-year period.

Financial institutions must issue refunds within two years of their settlement date. That deadline has already passed for some, while the process is ongoing for others.

Canadians learned of the unwarranted fees from the Ontario Securities Commission (OSC) after secret negotiations between the financial institutions and the OSC, the body that regulates them. The disclosures are the result of something called a no-contest settlement program introduced by the OSC in 2014.

No admission of guilt required

Those settlements mean none of the offenders had to admit wrongdoing or guilt; they simply agreed to fix the problem, pay back their customers and pay a fine.

It's a program the OSC's director of enforcement, Jeff Kehoe, calls "a huge success." But some are raising questions about it.

Stan Buell, president of the Small Investor Protection Association (SIPA), says these settlements are one more reason why his non-profit group, created to educate and advocate for consumers, feels there should be a public inquiry into the investment industry.

"These no-contest settlements are absolving the industry of the responsibilities for the last 10 years," he said.

"I mean, how can regulators claim that they protect investors when these companies have been doing this for 10 years undetected?" Buell asks, calling the settlements just a part of the "deception" of the investment industry.

'An easy out'

A former director of the OSC is also speaking out about the secret agreements.

"I haven't been a fan of [no-contest settlements] because I think it provides an easy out for people who have been involved in misconduct," Michael Watson, a former director of enforcement with the OSC, told CBC News. Watson is now a special adviser to the RCMP's integrated market enforcement program.

Watson said he has trouble seeing an appropriate resolution to such cases when no one is required to admit wrongdoing.

"I guess I was always concerned that if people were not prepared to stand up and admit they'd done something wrong that they might not see the harm in doing again," he said.

An adequate deterrent?

Lawyer Anita Anand, the J.R. Kimber chair in investor protection and corporate governance at the University of Toronto faculty of law, worries these agreements won't stop future wrongdoing.

"That is positive for the financial institution [but] it's not so positive for deterrence in terms of sending a message to the market that a certain type of behavior is simply not going to be permitted in Canada's capital markets," Anand said. "The law has to be seen to be fair and it is this perception of fairness that is my main worry."

Anand, like Watson, can see the benefits of the program in that the case doesn't drag on for years and investors do get refunds. Watson calls it a trade-off, adding it depends on what your objective is.

He points out the number of businesses coming forward to acknowledge overcharging clients speaks to the benefit of the program, since these are cases "that probably wouldn't have otherwise" become public.

Transparency issues

Anand wonders, though, whether the process is transparent enough and should be reviewed.

"The process occurs behind closed doors," she said. "It's not a trial. It's not a hearing. It's not a case in which you're going to have the public have access to proceedings in the way that you would with a trial or hearing. So there's less information coming forward on a daily basis about what is the process and the basis on which this no-contest settlement was reached."

Anand acknowledges the OSC does release no-contest settlement agreements, but not all documents leading to the agreements are made public "so again there is a transparency issue or at least a potential transparency issue there."

She said the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission's decision to pull back from using the settlements indicates "there are valid issues to be discussed here relating to transparency and legitimacy and ultimately the public's interest."

Kehoe says the OSC uses such agreements in limited circumstances and argues they do serve to prevent future problems, adding the settlements were introduced as a way of "getting the case done in a timely way, getting investor harm remediated and fixing the problems."

He said a no-contest settlement has all the hallmarks of every other hearing they do.

"A fine is a stigma and a deterrence no matter how you label it."

Just about every major investment firm has entered into a no-contest settlement.

What should investors do?

It is now up to the financial institutions to identify affected clients, determine how much each is owed, make "reasonable efforts" to contact those who have been overcharged and reimburse them. There is no established method for those clients to determine on their own whether they are owed money or how much. Investors with questions should contact their bank or investment firm.

Anand said there is no strong reason to believe the amounts that have been calculated are incorrect.

"They likely are [correct] but the process itself is somewhat disconcerting," she said, adding it doesn't inspire public confidence "given that we have so very little information about the process by which the so-called compensation plans are calculated."

Anand's advice to investors is to become more knowledgeable about their investments and Canada's capital markets. She said while financial literacy is important, it doesn't relieve regulators of their responsibility to protect investors and ensure a fair market.

Correction : An earlier version of this story said that CI Investments overcharged or underfunded clients by $156 million. In fact, they failed to pay interest on some clients' mutual funds.(Oct 19, 2017 11:07 AM)