From 'deadly enemy' to 'covidiots': Words matter when talking about COVID-19

So much has been said and written about the COVID-19 pandemic. We’ve been flooded with metaphors, idioms, symbols, neologisms, memes and tweets. Some have referred to this deluge of words as an infodemic.

And the words we use matter. To paraphrase the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein: the limits of our language are the limits of our world. Words place parameters around our thoughts.

These parameters are the lenses we look through. According to literary theorist Kenneth Burke, “terministic screens” are defined as the language through which we perceive our reality. The screen creates meaning for us, shaping our perspective of the world and our actions within it. The language acting as a screen then determines what our mind selects and what it deflects.

This selective action has the capacity to enrage us or engage us. It can unite us or divide us, like it has during COVID-19.

Metaphors shape our understanding

Think about the effect of seeing COVID-19 through the terministic screen of war. Using this military metaphor, U.K. Prime Minister Boris Johnson has described COVID-19 as an “enemy to be beaten.” He asserts that this “enemy can be deadly,” but the “fight must be won.”

Read more: War metaphors used for COVID-19 are compelling but also dangerous

The effect of this military language conflicts with the perpetuated myth that “we are all in this together.” But rather, it invokes aggressive combat against an enemy. It signals an us-versus-them divide, promoting the creation of a villain through scapegoating and racist attitudes. Naming COVID-19 as the “China virus,” “Wuhan virus” or “Kung Flu” places the blame directly on China and increases racism. Attacks against Asian people have dramatically increased globally.

Conversely, what would be the effect of a replacing the terministic screen of war with a tsunami? A metaphor that encourages “waiting out the storm?” Or working to help a neighbour? What would be the effect if the metaphor of “soldiers” were replaced with “fire fighters?” This could increase our perception of working together. Re-framing COVID-19 in this way has the capacity to convince us that we actually are “all in this together.”

An inspiring initiative, #ReframeCovid, is an open collective intended to promote alternative metaphors to describe COVID-19. The profound effect of altering the language is clear – to reduce division and generate unity.

Taking away our critical thinking

In a blog post, linquist Brigitte Nerlich compiled a list of metaphors used during the pandemic.

Although the metaphors of war and battle are foremost, others include bullet trains, an evil trickster, a petri dish, a hockey game, a football match, Whack-a-mole and even a grey rhino. Then there is the omnipresent light at the end of the tunnel.

And while they offer a way to re-frame our reality, helping the unfamiliar become familiar and rationalize our perceptions, there is danger lurking. Metaphors can substitute for critical thinking by offering easy answers to complex issues. Ideas can remain unchallenged if glossed over, falling prey to the trap of metaphors.

But metaphors also have the capacity to augment insight and understanding. They can foster critical thinking. One such example is the dance metaphor. It has been effectively used to describe the longer term effort and evolving global collaboration needed to keep COVID-19 controlled until vaccines are widely distributed.

COVID-19 buzzwords

Besides metaphors, other linguistic structures act as our terministic screens as well. Buzzwords related to the current pandemic have also increased.

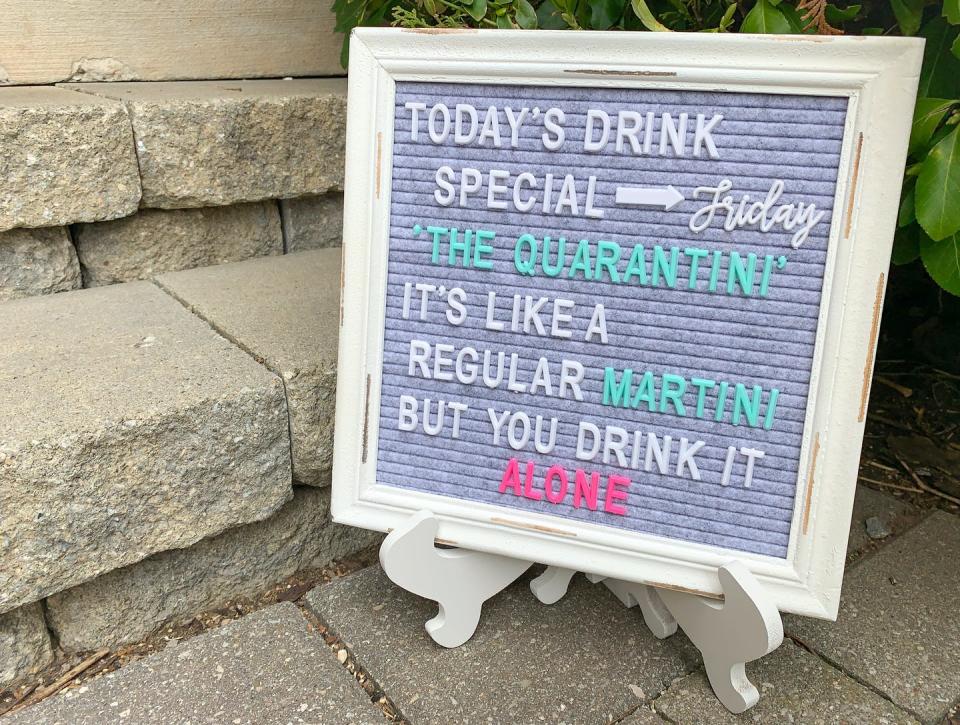

We grimace or laugh at covidiot, covideo party and covexit. Then there is Blursday, zoom-bombing and quaran-teams.

According to a British language consultant, the pandemic has fostered more than 1,000 new words.

Why has this happened? According to a socio-linguistic analysis, new words can bond us like “a lexical social glue.” Language can unite us in a common struggle of expressing our anxiety and facing the chaos. Common linguistic expressions decrease isolation and increase our engagement with others.

In a similar way, memes can reduce the space between us and foster social engagement. Most often sarcastic or ironic, memes about COVID-19 have been plentiful. Like metaphors, these buzzwords, puns and images embody symbols that invoke responses and motivate social action.

More recently, resisters of COVID language have flooded social media sites. Frustrated with the never-ending ordeal, online contributors refuse to name the pandemic. Instead they use absurd “pan-words”; calling it a panini, a pantheon, a pajama or even a pasta dish. These ludicrous words frolic with the terministic screen of “pandemic,” deconstructing the word to expose the bizarre meaningless nature of the virus and the heightened frustration with it.

Read more: How to cope with pandemic fatigue by imagining metaphors

The language used in relation to COVID-19 matters. As the effects of the pandemic intensify, so does the importance of the choice of language. Words, as terministic screens, can enable our perceptions in remarkable ways – they can unite us or divide us, enrage us or engage us, all while moving us to action.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts. It was written by: Ruth Derksen, University of British Columbia.

Read more:

Ruth Derksen does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.