Did Texas researchers link hunter deaths to deer disease? Not quite. Here are the facts

In Reality Check stories, Star-Telegram journalists dig deeper into questions over facts, consequences and accountability. Read more. Story idea? RealityCheck@star-telegram.com.

A group of San Antonio researchers have loosely connected a deer-specific disease to two human fatalities — which, if confirmed, would be the first known cases of the disease jumping from deer to humans.

The research publication this month triggered a flood of news articles, with at least one declaring directly that the deer disease had taken its first human lives.

Here’s the thing, though: The research, which took the form of a poster presentation at a neurology convention, doesn’t actually directly link the human deaths to the deer disease.

For decades, researchers have kept tabs on chronic wasting disease, a highly contagious and always fatal disease that’s similar to mad cow disease. Unlike mad cow disease — which is officially called bovine spongiform encephalopathy — there have been no known cases of CWD spreading from deer to humans. (The human equivalent of CWD, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease or CJD, is extremely rare and leads to dementia and death.)

If there was a confirmed case of CWD jumping to humans, it would be a big deal. But right now, even with the recent poster presentation, there are no confirmed cases.

Today's top stories:

→ What we know about Arlington Bowie High School shooting: Victim, suspect ID'ed

→ Fort Worth ISD to stop giving free school supplies to elementary students

→ Murderer had fixation with Bonnie and Clyde when he shot cop: witness

🚨Get free alerts when news breaks.

From the poster presentation, “I think we can conclude that somebody died of CJD,” said Krysten Schuler, the director of the Cornell Wildlife Health Lab and a longtime researcher of CWD. “What we can’t say is that there was any connection to chronic wasting disease.”

CWD was first identified in Colorado in the 1960s, and has now been found in 33 states, according to the USGS National Wildlife Health Center. CWD has been found in Texas deer, too, in counties across the state. The disease is of particular concern to Texas deer breeders, who face the culling of their entire herds if CWD is found on their farms.

While there have not been any confirmed cases of CWD infecting humans, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have long advised against eating venison from CWD-infected populations.

The question marks in the research have meant policymakers, hunters and deer breeders are on high-alert for any evidence that CWD could pose a risk to humans. The media, too, has caught onto the issue and dubbed CWD the “zombie deer disease,” much to the chagrin of almost everyone with a vested interest in wildlife.

[MORE: Texas rancher fights the state to save his deer herd]

The latest wave of public attention started earlier this month, when a group out of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio presented a poster at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology. The poster presentation was then converted into a brief publication in the academy’s journal.

The publication describes the death of a 72-year-old man who was a hunter “with a history of consuming meat from a CWD-infected deer population.” He died in 2022, of CJD. The man’s friend, also a hunter in the same area, had previously died of CJD, the publication says.

There are few additional details about the two deaths, or about how CJD was confirmed in the friend’s death. The researchers, through UT Health San Antonio spokesperson Monica Taylor, declined an interview request and also declined to provide details about where the two hunters lived. In an email statement, the researchers emphasized that the publication did not prove CWD transmission.

The publication itself is also clear that “causation remains unproven” and that more research is needed.

But, given the rippling of panic, the publication has garnered forceful pushback from special interest groups such as the National Deer Association, which called the publication “sketchy.” Researchers in the field have been less dismissive of the publication, but have also called for healthy skepticism.

Schuler emphasized that the publication is, at this point, “all speculation.”

“The first human case is going to be a big deal. It may impact thousands of hunters and their decision to go hunting or not,” she said. “But right now it’s hard because it’s not based on good information or a thorough investigation.”

Ellen Peters, the director of the Center for Science Communication Research at the University of Oregon, said that individual case studies might grab people’s attention, but they often don’t provide context on how common an illness actually is.

“Those kinds of stories, or labels like ‘zombie deer disease,’ can point toward what an experience is like or what it feels like, but it can’t tell us how common it is,” Peters said. “You have a story, you have an anecdote, you have a case study.”

Hunter Reed, a wildlife veterinarian for the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, said he felt the publication itself was clear about its limitations, and that there has been responsible media coverage of the study, too. At its heart, the publication calls for the same caution that state and federal agencies have been encouraging for years.

“We’re just still in the same boat as we’ve always been,” Reed said. “The guidance doesn’t really change, but still exercising caution.”

Both Schuler and Reed said that their main takeaway from the publication is that there needs to be more research into CWD, and into the origins of human CJD cases.

“The odds of CWD going into humans is extraordinarily low, but I can’t say that it’s zero,” Schuler said. “Unfortunately, time will tell.”

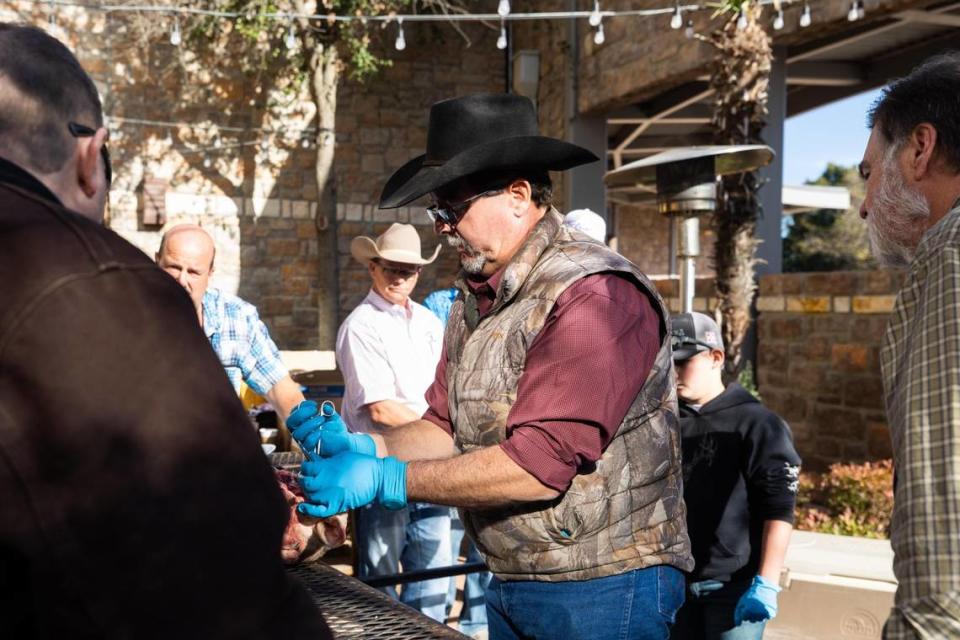

In Texas, the state Parks and Wildlife Department recommends that hunters have all their deer tested for CWD before eating any of the meat. If a deer tests positive, experts recommend not eating meat from that deer. In some parts of Texas, known as surveillance zones, CWD testing of harvested deer is mandatory.