How drones and AI could help stem the spread of a plant invading Quebec parks

Next time you're in one of Quebec's provincial parks, take a look around. Notice anything that shouldn't be there?

You likely wouldn't, as a pesky invasive plant wreaking havoc on local biodiversity, called the common reed, holds true to its name.

The alien grass can be spotted across much of the province and the country, spreading through marshes and in ditches along highways.

Tall with a woody stem and clusters of flowers that start purple and turn wheat-coloured, the common reed can also be found in seven of Quebec's 23 provincial parks — for now.

"The common reed is a really aggressive, invasive species, and when it arrives, it takes almost all the biodiversity," said Antoine Caron-Guay, a researcher at Montreal's Institut de recherche en biologie végétale (IRBV).

In Îles-de-Boucherville provincial park, located on a chain of islands on the St. Lawrence River between Montreal and the South Shore, large areas have been colonized by the plant, becoming giant reed beds that deprive the park's animals of food and habitat.

"There's a lot of interesting species here, and the common reed is like a threat to [them all]," said Caron-Guay.

Quebec's highest concentration of common reed is found in the park, according to Caron-Guay. So the researcher has begun experimenting with drones and artificial intelligence to map the plant's relentless spread in hopes of nipping it in the bud — so to speak.

How the technology works

Before you can stop the spread of an invasive species, you need to know where it can already be found.

While the mature common reed colonies are pretty easy to spot, as the reeds can grow more than five metres tall, Caron-Guay is trying to identify the plants while they're still very young, to stop them from getting a foothold.

To conduct his field research throughout May and September of 2022, he used two large drones to take a multitude of high-resolution aerial photos, flying them through the air to map the area below in detail.

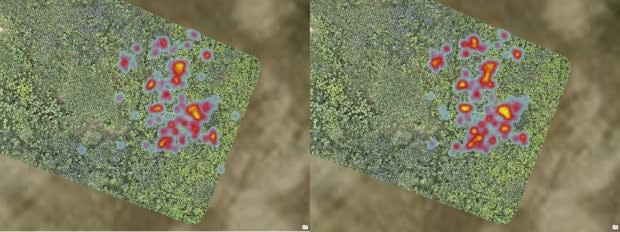

He took these photos back to a lab and fed them into an AI program that he trained to look for common reed plants from above.

Once the AI knows what it's looking for, it can analyze new photos in minutes or even seconds. Caron-Guay says his program, for which preliminary results show about 90 per cent accuracy, can be used to speed up the work of park conservation officers.

Sophie Tessier, co-ordinator of the conservation and education service for the Îles-de-Boucherville park, agrees.

"If you had … someone really go [out in] the field with a pen and paper, maybe taking pictures, maybe taking some samples, that would be a really long project without the drone," she said.

"But now, with technology, you could have lots of data and just maybe one person doing the work of, let's say, 10 botanists in the field. But that doesn't mean that technology will take over all the human aspects of it."

Common reed removal can take years

That's because humans still need to validate the findings of the AI — and even once you know where the plants are, you still need to get rid of them.

Caron-Guay says the smaller the plant, the easier it is to clear.

"You have to put local herbicide with a sponge, and it won't affect the environment around," he said. "But when you have a big colony, it is much harder."

Ripping out mature plants is difficult, as common reed can reproduce easily from a small piece of stem or rhizome left behind, meaning the earth around the plants must also be removed and replaced with uncontaminated soil.

As the plant hates shade, Caron-Guay said it can also be eradicated by covering it with a large tarp which deprives it of sun and suffocates it, but this process can take years.

Tessier says the park is using the tarp method, and it takes daily effort to make sure nothing is growing back.

Future of AI for other invasive species

Caron-Guay is now testing to see if the AI program can still give accurate results with lower quality photos shot by smaller, more consumer-sized drones, which are cheaper and don't require a drone pilot certificate to operate.

That would make this type of research more accessible to other researchers and possibly expedite conservation efforts.

The reduction of invasive species by 50 per cent by 2030 was a key goal agreed upon at the UN biodiversity summit, known as COP15, held in Montreal in December.

Étienne Laliberté, Caron-Guay's supervisor and a professor in plant ecology at Université de Montréal, says that Quebec's provincial parks are essentially open-air research labs where scientists can test out projects like Caron-Guay's and see the real-world impacts they have on conservation efforts.

Laliberté is already overseeing some other researchers who are also using drones for different aspects of biodiversity research. He believes this technology could have applications for other invasive species, too.

"I'm thinking, for example, in particular the water chestnut, which is an aquatic plant that is taking over rivers and lakes," he said.

"It's actually quite difficult, obviously, to find it because it moves around with the current, and so I think this technology … is sort of the first steps."

Laliberté said you could also likely use the same technology to map the impacts of pests like the emerald ash borer, an invasive beetle, by identifying damaged ash trees.

As for the future of the Îles-de-Boucherville park and the fight against the common reed, Caron-Guay is looking forward to the day when he can witness the fruits of his labour.

"It could be a small impact. I won't change the world, but I hope that someday, like in a few years, I could come here and see that there's a place where there's no common reed," he said.

Seeing the return of the least bittern, an endangered bird species affected by the loss of its natural habitat to the common reed, would also be a testament to his efforts.

"To see that this species could return to the Îles-de-Boucherville park would be truly magical. It would be seeing that my work has served a purpose."