In Elliot Page's new memoir, Halifax is as much of a main character as Hollywood

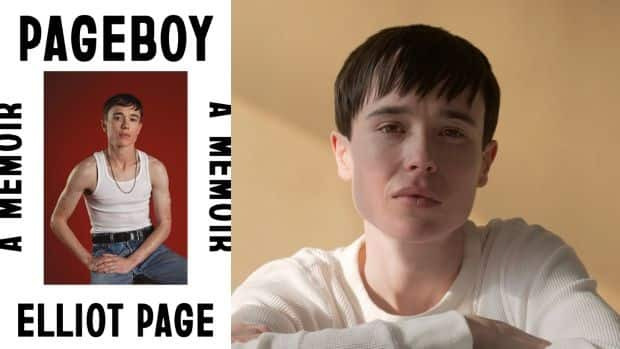

In Elliot Page's new memoir, Pageboy, the Oscar-nominated transgender actor writes about coming of age as a young queer person in Halifax and all the difficulties of growing up at a time, and in a place, rife with intolerance.

A recent New York Times book review of Pageboy described Page as "possibly the most famous trans man in the world," and there's no question that Page is the most famous queer Nova Scotian.

Page might be a celebrity, famous enough to have sat across from Oprah on her sofa on multiple occasions, but in Pageboy, Halifax is as much of a main character as Hollywood.

There's trips to the Halifax Brewery Farmer's Market downtown on Lower Water Street, "where I've spent countless Saturday mornings weaving through the crowds, collecting produce, eating fresh cinnamon buns, listening to the fiddle echo through the main hall."

He writes about nights at the Pavillion, an all-ages punk venue on the Halifax Commons, where teenagers mosh in "a pit overflowing with pubescent pheromones."

There's also bike rides around the city, like one instance where Page pedals across the peninsula to deliver a greeting card purchased at Biscuit General Store with "suggestive lesbian innuendo" to an unrequited crush.

Brushes with out and proud queer people for the first time, like at the Halifax Shopping Centre food court, where Page finds himself drawn to an woman working at The Healthy Way sandwich shop.

"Running into her on the sidewalk, seeing her at a party, eating the wraps she made at the mall, I didn't have a crush, but I yearned to be near what was possible. Her visibility meant the world to me," Page writes.

The beauty of the rest of the province is also on full display, on road trips to the Northumberland Strait, Cape Breton, Sable River, a cabin just outside Pugwash, and even an unnamed empty island where boaters are permitted to camp for the night, where Page recalls "stars pulsing, reaching, as if forming sentences"

First experience at a gay bar

In the opening chapter, Page describes going dancing at the now-shuttered Reflections Cabaret on Sackville Street.

It's his first time at a gay bar, and throwing caution to the wind, he leans forward to kiss the woman he's been dancing with. He finds himself "jolted by my boldness, as if it came from somewhere else, powered by electronic music perhaps, a circuit of release, of demanding you leave your repression at the door."

But growing up in Halifax wasn't always easy for Page as a young person discovering their sexuality and gender identity.

His day-to-day reality was often challenging, and he recalls a near constant hum of homophobia, always bubbling close to the surface and occasionally breaking through.

He writes of a teammate calling him a "dyke" at soccer camp, and how "things changed after that. Something had been severed. I could sense the whispers, a shift in energy, the speculation."

As a teenager, Page realized early on he needed to develop thick skin, even before his career in Hollywood necessitated it.

Afraid of coming out, he plunges deeper into the closet, going on dates with boys and trying to fit in with the popular kids by attending parties in the city's South End, "drowned in the stench of alcohol and sweat and horniness," where it was "unusual when someone didn't have to get their stomach pumped."

But it never quite works. On one occasion, while he's with another boy in Fort Needham Park, he's called a f----t, the first of many times he's subject to abuse for nothing more than his presumed sexuality and gender.

Making up for lost time

After Juno became a smash-hit movie in 2009, Page was nominated for an Oscar and his life changed forever. He was thrust into the public spotlight, losing control of his own narrative and considered fair game by paparazzi and the Hollywood gossip mill.

He wasn't spared back home in Halifax either, ending up on the cover of Frank Magazine, a local tabloid.

"I was in Santa Monica when my father called to tell me that I was on the cover, a photo of me from Sundance with a giant headline that read 'Is Ellen Page Gay?'" he writes.

"I spun out. In bed at a friend's guesthouse, I closed my wet eyes tight, tears soaking my cheeks. Please let this be a dream. Please."

Swept away by the machinery of Hollywood, Page goes back and forth between Los Angeles and Halifax for many years. He's told by people in the industry that it would be better if he presented in a more feminine fashion, and that it would hurt his career if he came out.

At just four years old, he recalls trying to pee standing up at the YMCA on South Park Street, and realizing "that I wasn't a girl. Not in a conscious sense but in a pure sense, uncontaminated."

It took many years for Page to come into his identity as Elliot and share it with the world, first doing so at the end of 2020. But now he's making up for lost time.

"I'm changing, I'm growing, it's all just beginning," he writes. "Let me just exist with you, happier than ever."

He's also conscious of all those in Halifax who came before him and never had the chance to come out in their own lifetimes.

He writes at length about the Halifax Explosion, discussing what it's like to come from a city that has had to rebuild and start over, not unlike he's had to in his own life.

"What did queer people do after the tragedy?" he wonders. "Those who lost secret lovers. The closeted grief."

As trans people come under attack across North America and here in Nova Scotia, Page's book also serves as a vital reminder of their humanity.

"The world tells us that we aren't trans but mentally ill. That I'm too ashamed to be a lesbian, that I mutilated my body, that I will always be a woman, comparing my body to Nazi experiments," he writes.

"It is not trans people who suffer from a sickness, but the society that fosters such hate."

MORE TOP STORIES