New exhibit at The Rooms gives voice to N.L. residential school survivors

For decades they were told to keep quiet about it but now a new exhibition at The Rooms focuses exclusively on what residential school survivors experienced at the five schools that operated in Newfoundland and Labrador.

It once was taboo just to talk about residential schools, says Toby Obed of Hopedale in a video of former students produced for the exhibit.

We were always put down. That was ... the hardest thing that I had to overcome. - Ivy Strangemore

"Don't mention the word. Don't talk about it. Don't say nothing about it. Leave it. Don't talk about it," says Obed in the video.

Another former residential school survivor talks about the lasting psychological impact of her time at one of the schools.

"We were always put down. That was the biggest thing that I found and the hardest thing that I had to overcome," said Ivy Strangemore of Makkovik, Labrador.

Maria Brown Brazeau, who now lives in Ottawa, speaks about how the schools worked to strip students of their languages and cultures.

"He said, 'Don't you ever speak your language again in this school,' with as much venom as he could muster," she says in The Rooms video, describing how she was spoken to by staff as a child at a residential school.

Coming full circle

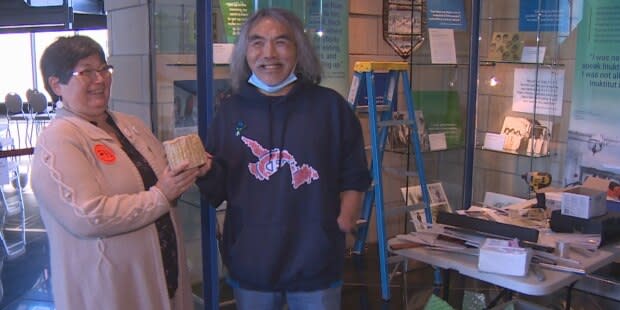

On Wednesday, Obed was in St. John's for the installation and opening of In Their Own Words: Life for Labrador Students at Residential School.

"It's come full circle from having a very hard fight it court to being here [at The Rooms] It's very significant. Very powerful. Now that it's more out in the open and people are more aware of it, it takes some of that weight off, some of that tension," said Obed, who was one of the first plaintiffs in the class-action lawsuit that saw the federal government pay more than $50 million to thousands of former Newfoundland and Labrador residential school students.

That almost decade-long court battle also resulted in residential school survivors receiving an apology from Canada's prime minister in 2017, when Justin Trudeau travelled to Happy Valley-Goose Bay.

It's emotional

Some items that were used at the apology ceremony, such as candles representing each of the aboriginal and indigenous groups in Labrador, are part of the show.

The exhibit includes many photographs of students who attended the schools over the decades following Newfoundland joining Canada in 1949.

"It's emotional. A lot of pictures of people we know," said Evelyn Winters, whose parents attended residential school years before she worked with residential school survivors herself.

"It's really good to see because it's our history. We've been there and our parents have been there [at residential schools], and it's so good to see it out in the open right now and hearing their stories and knowing what they have gone through. It's not hidden anymore."

The exhibition will be at The Rooms, on the third floor, near the provincial archives, until next October.

MHAs moved by exhibition at House of Assembly

On Thursday in the House of Assembly, Lisa Dempster, the minister responsible for Indigenous affairs and reconciliation, called the opening of the new show "a very powerful evening."

Dempster also reaffirmed the provincial government's commitment to apologize to residential school survivors, a promise made after Trudeau's 2017 trip.

"Our government remains committed to delivering apologies to former students of residential schools in this province when it is safe to do so," she said.

"By acknowledging the trauma felt by students and their painful memories, we make a commitment not to repeat the mistakes past but to learn from them."

Her words were followed by a statement by Torngat Mountains MHA Lela Evans, whose voice and hands shook as she spoke.

"Residential schools isolated indigenous children from their families and forcibly prevented children from speaking their ancestral language, disconnected them from their culture and traditions and forced them to adopt Christianity in order to assimilate them into Canadian society. It's a harsh reality and must not be forgotten," she said.

"I myself grew up with the ghost of residential school trauma in my community and within my own home. The wrongs done to Indigenous people through residential schools was not honourable."

Read more from CBC Newfoundland and Labrador