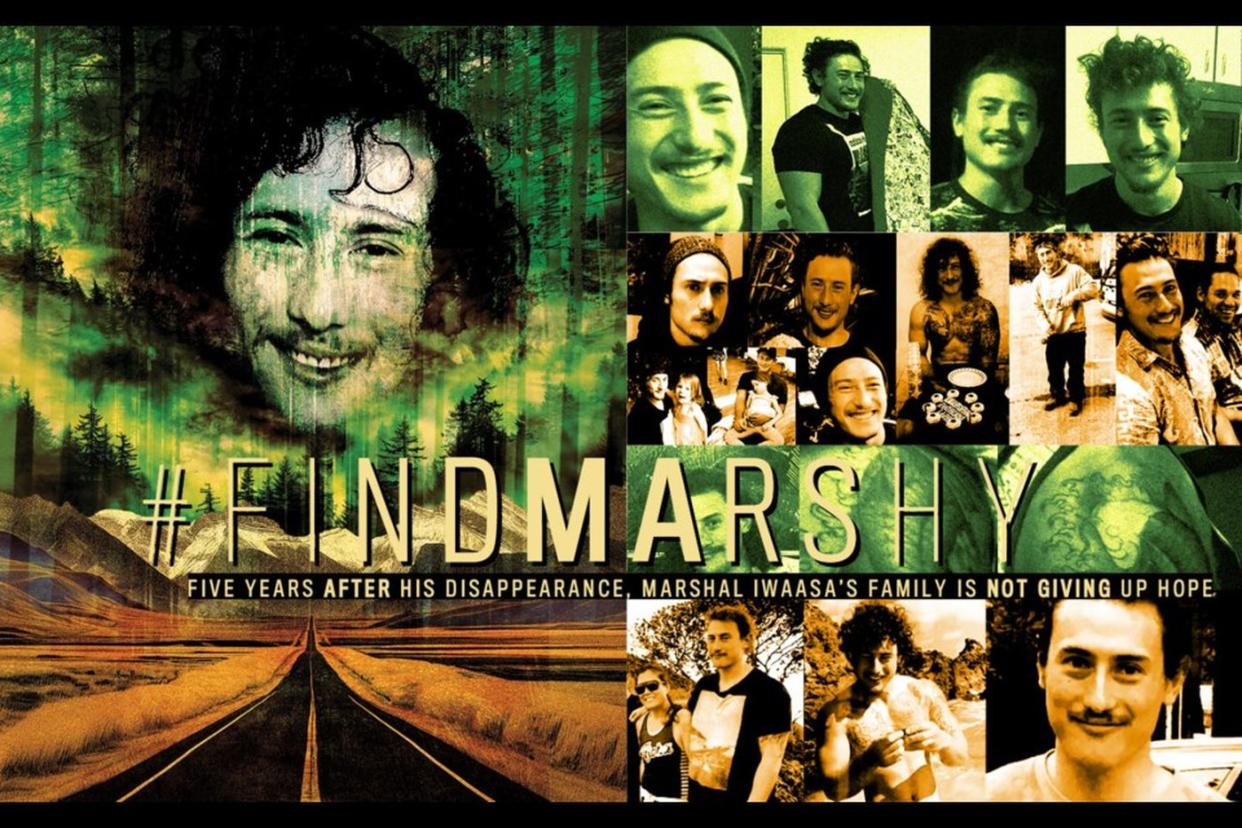

#FINDMARSHY

The Find Marshal Iwaasa Facebook page has 15,800 members and counting, many of them posting their theories, sharing encouragement, and showing a general devotion to finding the missing 26-year-old.

Five years after his mysterious disappearance in the Pemberton backcountry, interest in the case of the missing Lethbridge man is not dying down. People from all over the world are devoted to seeing it come to a conclusion.

But none more than Tammy Johnson, Iwaasa’s mom.

Johnson has not stopped looking for her son since the day he left her kitchen table in Lethbridge, Alta.—Nov. 17, 2019.

He helped her with problems she was having with her computer before leaving to head back to Calgary.

Iwaasa and his sister Paige shared a storage locker. The young man attempted to gain access to the unit several times that night before finally unlocking it at 6 a.m. He stayed in the area for two hours before disappearing into the unknown.

He has not been seen or heard from since that day.

Johnson’s life changed forever four years ago when every parent’s worst nightmare came knocking on her door. In an interview, she tells Pique the family is incredibly grateful for a resurgence in interest in Iwaasa’s puzzling case.

“It helps so much getting the word out there and increasing public awareness. We said for a long time that that is how we are going to find answers—through public awareness,” she says.

“It just feels like Marshal’s case is at a standstill. Nothing really has happened. It is very hard on us. People ask if we have thought about certain scenarios. I have to remind myself that they are interested in the case. The difference for me is that it is my son…

“I just always think that people care, and that’s the important thing. People reach out and truly want to help.”

Coming up on five years since Iwaasa’s disappearance, the family is still calling on the RCMP to upgrade the case to a criminal matter.

‘It needs to be talked about’

Over the phone, Johnson prepares herself to run through the same details she has focused on for the past four years.

“It’s difficult to talk about, but it needs to be talked about,” she says.

Iwaasa’s financial trail ended Nov. 15, 2019. On Nov. 23, a group of hikers found his burned-out truck in a dense wooded area north of Pemberton—more than 1,200 kilometres away from his home. Personal items were scattered around the dark blue, 2009 GMC Sierra truck, including two passports, three cell phones, a smashed laptop, ID cards, toiletry bags and clothing. The route to the trailhead is inaccessible by GPS, requires a four-wheel drive, and is a 14-hour drive from Lethbridge.

Iwaasa’s family insists he had no links to the area, and had never even mentioned it before. After four years of extensive searches both underwater and from the air, nobody has been able to figure out what happened to Iwaasa, the shy 26-year-old who would go hungry rather than speak up.

“Marshal was always really shy and quiet, even when he was just a young kid. We would go into Subway and Marshal wouldn’t be able to tell them what he wanted on his sandwich,” Johnson says. “As he was getting older, I felt it was important for him to do it. Even with that, he wouldn’t order one. He would rather not have one at all.”

Iwaasa played sports growing up, and loved going camping with family and friends. He was a hard worker as a teen, earning a wage in his local grocery store and later taking on manual labour jobs in southern Alberta. Iwaasa and his sister Paige were best friends. When she relocated to Hawaii, annual family Christmas vacations moved there, too.

Johnson rejects theories her son died by suicide. She stresses her son’s introverted nature was completely normal.

“The police say that Marshal was shutting down,” she says. “Lethbrige Police Service (LPS) immediately jumped to thinking that Marshal killed himself. They backed that up saying that he was withdrawing from the family and he wasn’t forthcoming with the fact that he was no longer in school. Marshal is so shy. He just didn’t talk a lot. He just didn’t. Their misread of the situation has really been detrimental to us.”

Assumptions and confusion

Johnson can be forgiven for feeling the case is at a standstill. Getting clear information from officials is no easy feat.

When Pique reached out to the Whistler RCMP for an update on Feb. 6, Staff Sgt. Sascha Banks said the Lethbridge Police Service (LPS) was leading the investigation.

That same day, Kristen Saturley, with the LPS, told Pique the file was transferred to Pemberton, and the LPS no longer had jurisdiction.

Pique circled back to the Whistler RCMP, and was told “it appears there is a transfer of the file happening to Pemberton but we have yet to receive the file from Lethbridge. A review will be conducted of their investigational details.”

But when Pique again reached out for another update, months later, RCMP said they still did not have the file, which remained with the LPS.

Pique circled back to Saturley, with the Lethbridge police, who said the detachment “has an open and ongoing investigation, and continues to collaborate with other law enforcement agencies.”

In explaining the confusion, Insp. Robert Dykstra, officer-in-charge of the Sea to Sky RCMP, noted determining police service of jurisdiction is based on where an incident takes place, and not where the involved persons may end up. With Iwaasa’s vehicle being found in Pemberton, “there have been recent discussions about police service of jurisdiction given where follow up investigative work is likely to occur,” Dykstra said. “Initial consultations at the investigative level were conducted but not finalized at senior levels where authority to make these decisions rests.”

As it stands, the LPS remains the lead on the file, with the Sea to Sky RCMP assisting closely, Dykstra said.

Since Pique’s initial inquiries in February, the LPS has received and investigated multiple tips from the public, Saturley said.

“The information provided was determined to be either unsubstantiated or unfounded. As this case is open and ongoing, in order to protect the integrity of the investigation, LPS will not provide further information related to active investigative steps,” she said.

“Any new information, tips or evidence that comes to light, will continue to be thoroughly investigated. Anyone with information that would benefit the investigation is asked to call Lethbridge Police at 403-328-4444 or Crime Stoppers 1-800-222-8477 / www.p3tips.com.”

As for upgrading the case to a criminal matter, police still don’t have enough credible information, Saturley said.

“The case has garnered significant attention on social media platforms, podcasts and other mediums, which has resulted in many assumptions, rumours and a great deal of speculation,” she said. “From the onset of this investigation Mr. Iwaasa’s disappearance has been considered suspicious, however there is no credible, corroborated or compelling information to suggest foul play or that the occurrence is criminal in nature.”

A normal visit

Prior to his disappearance, Iwaasa moved to Calgary to study a computer program at the Southern Alberta Institute of Technology. In the summer of 2019, his family assumed he would be returning to school in the fall. It was only after his disappearance they discovered he had dropped out.

The young man had previously stressed to Paige there were other ways to go about his career. Johnson has agonized over every conversation she had with her son before his disappearance over in her head.

“When I was talking to Marshal, I would say that I was so proud of him. He didn’t love school—he got through school,” she said. “It didn’t come easy for him. When we did find out that Marshal wasn’t enrolled for the next semester, I wished I had told him that he didn’t need to be in school. I was just proud of him for trying. Maybe he needed me to say that it was OK.”

Their last meeting, on Nov. 17, was entirely normal no matter how many times Tammy plays it back in her head.

“He stopped in. He sat at the table in my kitchen,” she says. “He worked on my computer. We chatted a bit. There was nothing that I could specifically say that was different about him. There was nothing different about him. There was no warnings or red flags or anything. He was Marshal, my kid. I go back over and over and over that last visit trying to find out was there something I missed. There was no indication that there was anything wrong.”

Johnson was always the chatterbox of the two of them.

“It was a normal visit with Marshal. I was talking and talking,” she says. “He was answering ‘yes’ or ‘no’. Marshal is just Marshal—easygoing and quiet.”

A place called Pemberton

Johnson was on vacation in Hawaii when she got the call no parent wants to get.

“I had just been there for four days when we got this call that Marshal’s truck was found in Pemberton,” she says. “We were in shock. We couldn’t find out what was going on.”

The experience was “a total mind-f***,” Johnson says, remembering how police showed the family photos of the truck.

“When I saw those pictures, I was so scared. I was scared for my son. I was shocked by the amount of damage that was done,” she says. “I felt that someone had deliberately set it on fire. They torched my son’s truck. That was my immediate reaction.”

The family’s gut feeling has always been foul play was involved.

“It was not just that his truck had been abandoned somewhere,” Johnson says. “The police were saying that they weren’t sure if it was set on fire. How? It was absolutely arson.”

Pemberton was just a place on a map before the family received that life-altering call.

“To our knowledge, Marshal had never ever been there,” Johnson says. “Marshal and Paige were very, very close. If Marshal had ever gone to Pemberton, the one person who would have known would have been Paige.”

She feels Iwaasa would have gone camping elsewhere and would have always brought a buddy.

“If Marshal wanted to go camping or hiking, they went down to glaciers in Montana, Waterton, those kind of places,” she says. “We didn’t know anything about Pemberton. We were just wondering how in the world this happened.”

‘This is not a place you drive your vehicle to’

On Nov. 23, 2019, James Starke and a group of hikers were headed up to Brian Waddington Hut northeast of Pemberton when they found Iwaasa’s truck at the end of the trail.

Built in 1998, the hut houses more than 25 people, but requires a reservation. Starke and his group were the only names on the list that day.

Starke shared his account in the South Coast Touring Facebook group.

“Had a crazy experience this weekend trying to get to the Brian Waddington Hut,” he wrote. “We took the 4x4 trail all the way to a burnt-out pick-up truck that smelt very fresh. In addition, there were possessions thrown all over the area. It felt like a crime scene and had a very eerie feeling. We turned around and left, deciding not to hike to the hut with a fear of walking into something.”

It was later determined parts of Iwaasa’s truck were missing. Things would continue to be moved and taken from the scene over the following years. Some of his belongings were never found at the site, including his contact lenses and wallet.

The family were not able to make it to the scene themselves until July 2020.

The remoteness of the trail took them aback.

“We couldn’t even take our vehicles up there,” Johnson recalls. “The RCMP went up and one of their trucks got damaged going up there. A local jeep group volunteered to bring us up.”

The trip just solidified the family’s initial theories.

“This is not a place you drive your vehicle to. This is a place you dump a vehicle at,” Johnson says. “That was our feeling. Marshal had just paid off his truck. There was not a chance that he had gone through all that or even been able to find that place. You have to be familiar with it. People who live in the area have told us that repeatedly.

“However this truck got up there, the people knew the area. Marshal didn’t know the area. He had never been there. It was just making no sense.”

Tammy’s maternal instinct kicked in, and she did everything she could to try and find her child. A mission to try to gain CCTV footage from gas stations proved fruitless.

“A friend of mine and I drove from Lethbridge to Revelstoke in December of 2019,” she says. “We went to put posters up of Marshal. We stopped at service stations and asked them to see the CCTV. We asked them to keep the window of surveillance that we needed. They repeatedly told me that it would have to be police-enforced… that the police would have to request it.”

Johnson took down each manager’s name, along with their numbers and the addresses of the gas stations. She wrote down what they said, and that the police needed to request the information.

“I did all that groundwork,” she says. “I gave all that information to the LPS, and was anything done with it? I don’t know.”

Too many cooks

Johnson believes the involvement of multiple police forces has complicated matters from the very beginning.

“You have three different law-enforcement groups,” she said. “Then it comes to like, tossing a potato. We got the runaround. We feel that law enforcement groups were able to say that it wasn’t their jurisdiction. It really complicated things, having three involved.”

A lack of communication from police has caused a lot of hurt to the close-knit family.

“As a family, we have no idea what has been done by LPS. The communication we have had with them is limited at best,” Johnson says. “They are telling us that they are doing what they can. They are telling us that they are following every lead. At the end of the day, we have no more answers than we did at the beginning. It is four years in, and we don’t know anything.”

The family believes things would have been extremely different if Iwaasa’s case was deemed criminal.

But in their experience, everything they do is met with pushback from law enforcement.

“We wanted Marshal’s case deemed as a criminal one. We felt very strongly about this,” Johnson says. “Marshal wouldn’t have gone up there on his own. We felt it was arson. We wanted this to become a criminal matter so things would really open up. We felt that the police were dragging their feet.”

A petition for the case to be upgraded to a criminal one has gained more than 6,000 signatures, “but they said it didn’t matter how many signatures we had,” Johnson says. “We are struggling to find out what they needed to deem it a criminal case. They said for a long time that it’s suspicious, but that doesn’t mean that it’s criminal. It needs to have that designation in order to open up a full investigation. LPS took months and months to dust for fingerprints at the storage unit, the last place that we know Marshal was at. Even with that, they were dragging their feet. I don’t what their reasoning for that was.”

Johnson said officers suggested Iwaasa might not want to be found—that he had every right to disappear if he so wished.

“I get that, absolutely. If you want to go away, that’s your right as a human being,” Johnson says. “But look at the truck. Look at where it was, look at all the stuff that you can just see. There were things that didn’t belong to Marshal at the scene.”

The mother who has advocated for her shy son since the day he was born is not ready to stop any time soon.

“It’s really frustrating as a family to feel that we can see this. It seems like it’s so easy. Something terrible has happened to Marshal,” she said. “I am not a police officer so I don’t know what the threshold is. As a family looking for a loved one, you feel like nobody cares. It feels like nobody is doing a thing to find out what happened to Marshal. He gets lost in all of this.”

Tammy believes that if her son had intended to go camping in the area, he would have taken camping gear from the storage unit. “We felt like this was this was all only pointing in one direction,” she says.

A link in the chain

Recent documentaries have linked Iwaasa’s case to the case of another missing man. Thirty-year-old Daniel Reoch was last seen in the Squamish Valley on Nov. 25, 2019. He was reported missing on Jan. 7. Johnson said Reoch’s family got in touch when they saw photos of the possessions scattered around Iwaasa’s truck—which they said looked like Reoch’s.

“Daniel went missing a couple of days after Marshal’s truck was found … We feel like there is a possible connection, for sure,” Johnson says. “We just hope that it has been investigated. The family have contacted us and we have contacted them.”

The family hired private investigators in the hope of getting some much-needed closure. The investigators scoured the scene in June 2020, where they found a Zippo lighter.

“That was left at the scene. What else was left? Who knows?” Johnson says. “We don’t want to speak badly of law enforcement, because we need them. I just wondered if they would have proceeded in the same way if it was their son who was missing. I doubt it.”

The private investigators carried out their own fire report, and concluded the truck was torched via arson.

“He saw the points of ignition and an accelerant was used,” Johnson says. “The fire report from the police that finally came back was inconclusive.”

Left on the trail for years, where hikers posed for snaps with its burned-out body, Iwaasa’s truck was unceremoniously hauled away late last year—a heartbreaking development for Iwaasa’s family.

Varcity Outdoor Club’s Jeff Mottershead decided to move the wreck, fearing it an environmental hazard.

“There might have been oil leaking into the earth and things like that. I can understand. I just would have thought that they might have reached out to us and given us the heads up before anything was done,” Johnson says. “We felt that if this was a criminal matter, then that would be evidence.”

Tammy doubts the truck concealed any answers, having been left out in the elements in the rugged area. “The reality is that it was just left up there anyway,” she said. “Could anything that could have come from the truck still be used as evidence if it had been sitting up there for years? Probably not.”

In limbo

Iwaasa’s family is campaigning for systematic change in the way missing person cases are treated. According to the RCMP’s National Centre for Missing Persons and Unidentified Remains, there are approximately 500 cases left unsolved every year.

“I don’t think we are the only family who have had this. Missing people just get left,” Johnson says.

“It feels like nothing really gets done. As a family I just feel like instead of working with us, law enforcement were working against us. It was already so incredibly difficult. Feeling like you have to fight with law enforcement to do anything just adds so much more hurt, stress and heartbreak.”

Iwaasa’s case has been through four different officers with the LPS, she adds.

“There’s not one consistent person. We are hoping that someone comes forward and gives the police some information to get us some answers.”

For now, Iwaasa’s family remains in limbo, hoping someday they will find out what happened to the curly-haired, gentle man they love so much.

Roisin Cullen, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter, Pique Newsmagazine