First Nations aim to capitalize on economic opportunity of legal pot industry

First Nations want to be among those cashing in on what could become a multibillion-dollar industry if the federal government follows through on making marijuana a legal recreational drug in Canada.

The Trudeau government's goal is to make legalization a reality on or before July 1, 2018. Several First Nations are already trying to get into into the business of producing pot.

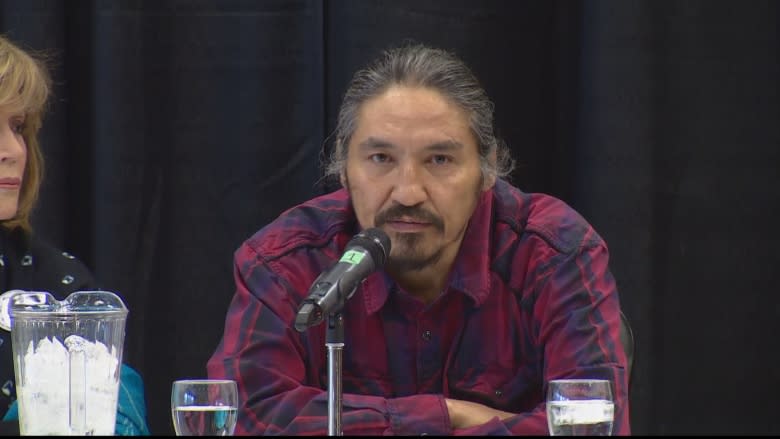

"It means economic opportunities for First Nations people … and so many First Nations across this country are in such dire straits," said Allan Adam, chief of the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation, a fly-in community in northern Alberta.

Getting in

Allan said his community is exploring investing in a company that's already producing medical marijuana — as a start. If recreational marijuana is legalized, he said, the First Nation will already have its foot in the door.

"Until it becomes recreational, we have to invest in medical."

Other First Nations have gone beyond exploring and have invested millions in cannabis ventures, like the Wahgoshig First Nation near Kirkland Lake, Ont., which partnered with an Ontario company called DelShen Therapeutics in 2015 to convert a former forestry operation into a facility that will grow "pharmaceutical-grade" pot.

Former Assembly of First Nations head Phil Fontaine also recently moved into the medical marijuana business with his company, Indigenous Roots.

"Our primary interest here, of course, is business opportunities, job creation. It's about the Indigenous economy, job opportunities, and it's about training," Fontaine told CBC News in December 2016.

Business opportunities

The Mohawk Council of Kahnawake in Quebec announced in March that it was on a "fact-finding mission," seeking information about the medical cannabis industry. The community's website says the council now has a Cannabis Working Group.

In an email, political press attache Joe Delaronde said the council "has made no secret of its very preliminary exploration of potential business opportunities in the medical marijuana field."

In an appearance on Kahnawake Television, a local station, council Chief Rhonda Kirby said leadership was also investigating other possible opportunities.

"We are looking for partnerships with people that are already licensed providers, and in anticipation of the federal law being passed in 2018, what would that mean for the community if a recreational [marijuana] law was passed?"

At the Assembly of First Nations annual meeting in Gatineau, Que., in December 2016, chiefs unanimously supported a resolution introduced by Chief Adam, which directs the organization to push Ottawa for "priorities and incentives to ensure that First Nations are given the opportunity to participate and benefit fully from the development of this new and emerging sector."

Risks vs. benefits

One issue that's likely going to come up when First Nations invest in recreational marijuana, Adam admits, is the health aspect — especially in those communities that are already grappling with addiction issues.

While he's willing to make money off any new pot industry, Adam said there still needs to be discussion between Canada and Indigenous communities before legalization.

"You can't just impose something that's going to have detrimental effects on our communities," he said.

He wants to see money from the business of pot invested in programs in First Nations communities, especially those aimed at youth.

"It's a win-win situation for Canada and it's a win-win situation for First Nations."