Former Marion vice mayor sues over raid, claiming it was a ‘pretext for punishment’

The former vice mayor of Marion, Kansas, whose home was searched by police in August along with the local newspaper, filed a federal lawsuit against the city and a host of local officials and law enforcement officers on Tuesday, alleging they violated her First and Fourth Amendment rights.

Ruth Herbel, an 81-year-old former Marion City Council member, alleged in the lawsuit that former Mayor David Mayfield and his allies — including the former Police Chief Gideon Cody and Marion County Sheriff Jeff Soyez — orchestrated a conspiracy to get her out of office and silence her for criticizing Mayfield’s actions in the local newspaper, The Marion County Record.

“Mayfield is the driving force behind this because he doesn’t like me,” Herbel said Wednesday at a news conference at the federal courthouse in Wichita. “Because I have been a thorn in his side.”

“For her tireless efforts to stamp out corruption and mismanagement in city government, she was forced to endure an illegal and retaliatory search of her home,” Institute for Justice lawyer Michael Soyfer said at the news conference. “Ruth and the Institute for Justice have partnered to bring this lawsuit to send a message to Mayor Mayfield, Chief Cody, all of their co-conspirators and government officials across the country who would use investigations to silence political opposition. “

The 88-page lawsuit comes nine months after the police raid, in which Marion’s then-Police Chief Gideon Cody led law enforcement officers on searches of the newspaper, the home of the paper’s editor and owner, as well as Herbel’s residence. The searches provoked a national outcry and Cody later resigned.

Before the searches, the Record had been investigating Cody’s tenure at the Kansas City Police Department, where he was facing possible disciplinary action for allegedly making sexist comments. In applying for the search warrants, Cody wrote that he was investigating alleged identity theft of local restaurant owner Kari Newell after a reporter looked up her driver’s license records— which are public records — on a state database. The search warrant application for Herbel closely matched those drafted for the Record’s office and the home of the Record’s editor and publisher, Eric Meyer.

Herbel’s lawsuit is the fifth lawsuit filed over the raid, which include suits brought by Record editor Eric Meyer, current and former Record reporters and the Record’s office manager. The legal challenges have shone a spotlight on Fourth Amendment rights in Kansas — and the numerous violations of constitutional rights by law enforcement statewide alleged over the past decade.

Herbel, through her attorneys, says in the lawsuit that Mayfield “instructed Chief Cody to open an investigation” into his administration’s chief critics — Herbel and the Marion County Record — with the goal of silencing political dissidents.

“While Ruth was on city council, she was frequently outspoken against the mayor and his allies,” Jared McClain, Herbel’s lawyer from the Institute for Justice, said Wednesday. “She fought for honesty and transparency in government, and that upset the people in power. Mayor Mayfield tried repeatedly to silence Ruth while she was in office. And eventually he decided that the only way to do so was to have her arrested and removed from office.

“So he had some of his buddies draw up a bogus warrant to search Ruth’s home, along with the Marion County Record’s offices and the home of the Record’s publisher,” McClain said. “There was no real investigation. There was no evidence there were no crimes, it was just pretext for punishment.”

Cody, who had search warrants, said he was after evidence that the paper had violated privacy laws in looking up the driver’s license records of Newell.

The Kansas Department of Revenue has said the records were public and the newspaper has vigorously denied any wrongdoing. The local prosecutor also withdrew the search warrants days after the raids. Herbel had received a copy of the business owner’s criminal history from Pam Maag, a friend of Newell’s, which she forwarded to the Marion city administrator.

The Colorado Bureau of Investigation has been examining the raid, as well as the allegations involving The Record, after the Kansas Bureau of Investigation asked the agency to take over. Sedgwick County District Attorney Marc Bennett and Riley County Prosecutor Barry Wilkerson have been appointed special prosecutors on the case.

CBI spokesman Rob Low about a month ago said the prosecutors asked for some additional investigative steps. Low on Tuesday had no update, saying only that his agency was “still working on the additional investigative steps.”

Herbel’s husband, Ronald Herbel, is a co-plaintiff. They’re suing the city of Marion, Mayfield, Cody, acting Marion Chief Zach Hudlin, Marion County Sheriff Jeff Soyez, Marion County Sheriff’s detectives Aaron Christner and Steven Janzen, Marion Mayor Michael Powers and the Marion Board of County Commissioners.

Lawyers for Mayfield and Cody declined to comment.

Herbel and Mayfield clash

Tensions between Herbel and Mayfield — who ran together as a slate of candidates promising “positive change” and “honesty, integrity and transparency” in 2019 — started two years before Marion law enforcement officers raided the vice mayor’s home, according to the lawsuit.

Herbel often clashed, in public and in private, with Mayfield at Marion City Council meetings over how much information about city government should be discussed in public.

“It wasn’t any secret that David Mayfield and I clash because I’m the one that does a lot of research,” Herbel said at Wednesday’s news conference. “State statutes, codes and everything else. Mayfield doesn’t like that. He doesn’t like to be called out on something.”

It started small, the lawsuit says, with Herbel blocking Mayfield’s plans to raze a memorial fountain in Marion’s Central park — and escalated when Herbel told the Record about discussions during an executive session when Mayfield fired the city administrator based on “secret complaints” he refused to disclose to three of five council members.

Mayfield began trying to control what questions Herbel could ask during council meetings. Behind closed doors, during executive sessions, Herbel was subjected to verbal abuse from Mayfield and his “protégé” Zach Collett, another council member who would later tell Newell that Herbel was trying to block her from getting a liquor license, according to the lawsuit..

Mayfield once called Herbel a “bitch” during an executive session, the lawsuit says. Collett told Herbel that if the former city administrator were still around, “you would not be sitting in that God damn seat,” according to the lawsuit.

The open hostility played out publicly on the front page of the Marion County Record with headlines such as “Herbel, Mayfield continue to clash.”

Failed attempts

The hostility between Mayfield and Herbal escalated further in 2022 when Mayfield and his allies on the council passed a charter ordinance that would make it “dramatically easier for the city to issue bonds to fund the mayor’s projects,” the lawsuit says. It would have increased the types of projects Marion could fund through debt, eliminated a requirement for oversight by an engineer, allowed the issuance of bonds without a super-majority of council voters and eliminated a requirement that the city hold a referendum to accrue more debt.

Herbel voted against the change. She then organized a campaign against it and spent her own money on advertisements to defeat it. In a special election in December 2022, voters rejected the proposed charter ordinance 10-to-1, with just 25 of 294 votes in favor of his proposed changes.

That was the final straw for Mayfield, Herbel’s lawsuit says.

The next month, Mayfield and his wife, Jami Mayfield, organized a petition drive to have Herbel removed from the Marion City Council. Jami Mayfield posted on Facebook that signing the petition would help “recall Councilor Herbel and silence the MRC (Marion County Record).” They failed to get enough signatures to put the recall on a ballot.

Two months before the raids, Mayfield tried to get Herbel to sign an agreement saying she – as an elected member of the Marion City Council – was an “at-will” employee who could be fired by Mayfield. Herbel crossed out that part of the agreement but the city administrator would not accept it.

So when Herbel and the Record raised questions to Marion city officials in August 2023 about Newell’s driving record – including how she may have evaded Marion city and county law enforcement for 20 years while driving on a suspended license – Mayfield and his newly appointed police chief, Cody, snapped into action to retaliate against the mayor’s two harshest critics, the lawsuit says.

In response, Mayfield ordered Cody to investigate Herbel and the Record, the lawsuit says.

Three city officials – Mayfield, Cody and Collett – then reached out to Newell and fed her a false story that was then used as a pretense to open an investigation into Herbel and the Marion County Record, Herbel’s lawsuit says..

“The three city officials left Newell with the false impression that Ruth had (1) illegally obtained a copy of her driving record; (2) posted the letter on Facebook; and (3) planned to use the letter to oppose Newell’s catering license,” the lawsuit says. “Beyond those false statements, Mayor Mayfield told Newell that the only way to stop Ruth and get her off the city council was to have her arrested and charged with a crime.”

Herbel’s lawsuit contends that Cody’s warrants – which were later rescinded by Marion County Attorney Joel Ensey – lacked probable cause, were overly broad and were based on “lies and omissions.” It also says the search warrants were mishandled by Magistrate Judge Laura Viar, who signed the warrants without Cody being present to provide a sworn statement attesting to the warrant affidavit’s accuracy.

“The warrants were based on lies and omissions rather than probable cause,” the lawsuit says. “No one even swore the allegations were true. To make things worse, the warrants were also absurdly overbroad. But that hardly mattered because the police just took every phone and computer, without bothering to limit their searches to the terms of the overbroad warrants they drafted. The warrants, after all, were just a means to punish their critics.”

Judge shopping, suspect signatures

Herbel’s lawsuit alleges that the officials behind the raids went out of their way to find a judge would sign off on the “bogus warrants.”

“Rather than bringing the warrant applications to the District Judge for Marion County, the Honorable Susan Robson, the Defendants found a more favorable judge: Morris County Magistrate Judge Laura Viar,” the lawsuit says.

“Magistrate Viar was the ideal candidate for the conspirators,” Herbal’s lawsuit says. “She and Kari Newell shared a similar criminal history and benefited from a similar lack of criminal enforcement.”

A Wichita Eagle investigation found Viar had two DUI arrests while she was a prosecutor in Morris County. While on diversion for the first arrest, Viar was arrested again in a different county after she crashed a vehicle into a school.

“There is, however, no record of Magistrate Viar’s second DUI—which should have been a violation of the diversion program—because much like with Kari Newell, local law enforcement chose not to enforce the law against her,” Herbel’s lawsuit alleges.

Cody applied for four search warrants, one each respectively for the Record’s offices and the homes of Eric Meyer, Ruth Herbel and Pam Maag, the person who had originally provided Newell’s records to the Record and Herbel. Viar signed off on three of the warrants and rejected a warrant for Maag’s residence for unknown reasons.

Herbel’s lawyers also accused Viar of making a false statement on the applications.

“For the three warrants that Magistrate Viar signed, she crossed out the line for the notary’s signature and signed in the notary’s place—even though the ‘affiant,’ Chief Cody, was not present to swear to the application’s truthfulness. Because Chief Cody did not appear before Magistrate Viar, her statement that the applications were ‘subscribed and sworn to before me’ was obviously false.”

Whether that decision violated judicial ethics rules is under investigation by the Kansas Commission on Judicial Conduct, the second such inquiry into Viar’s handling of the warrants. An earlier complaint about her approving a warrant for a news organization instead of a subpoena was dismissed in December. The commission’s investigations, findings, hearings and final dispositions are typically confidential.

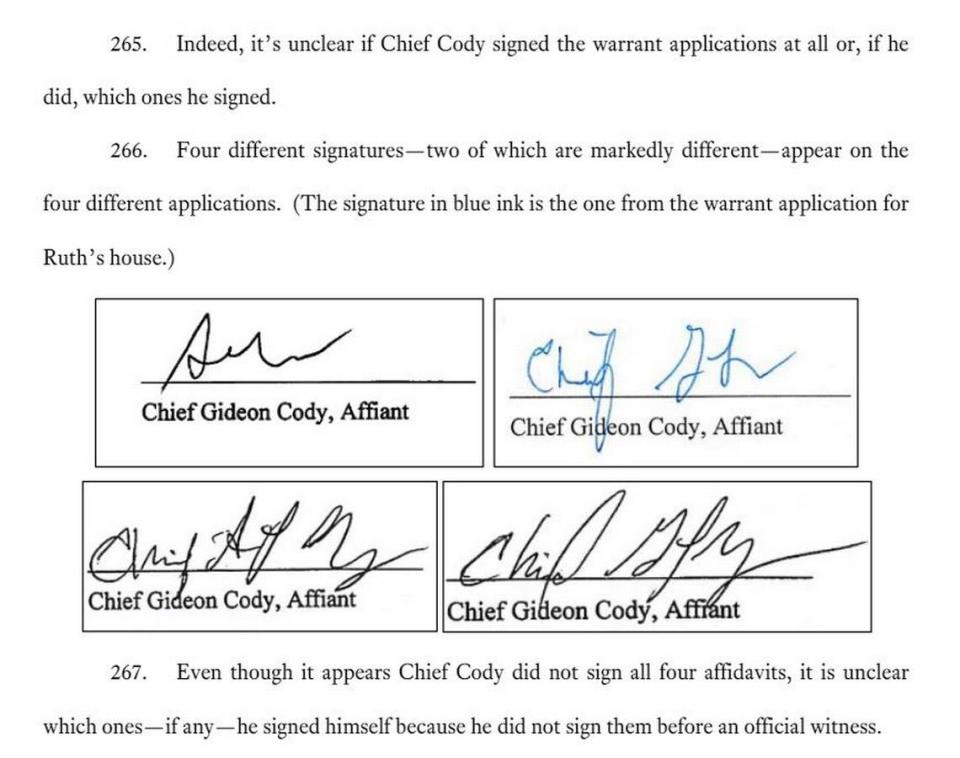

Herbel’s lawyers claim Viar’s decision to sign the unsworn warrants raises questions about whether Cody — or someone else — signed his names on the warrant applications. Herbel’s lawyers contend that the four signatures for his name on the applications are so different that it’s possible he didn’t sign any of the documents.

“The oath-and-affirmation is supposed to ensure that someone with personal knowledge swears under penalty of perjury to the truthfulness of the allegations supporting a warrant application,” the lawsuit says. “But no one swore to the contents of these four applications. Maybe no one felt comfortable swearing to the truth of these warrant applications, considering the material lies and omissions contained within and the complete lack of probable cause. Or maybe no one cared to follow even basic procedures.”

McClain said a common theme he sees in civil rights cases across the United States is a concentration of power in a few hands and a officials at multiple levels of government who refuse to stand up against unconstitutional actions. In Marion, that included the city’s elected and appointed leaders, officers with the police department, the sheriff’s office, the local prosecutor’s office and the person who should have been the last line of defense: the magistrate judge.

“They all just went along and fell in line,” McClain said. “And I do think it’s endemic in these places where power is consolidated in too few people, and there’s not enough consequences for their actions. And you see that in the fallout from this, where there were no consequences. The County Sheriff’s Office, the City Police Department, the City Council — no one has stepped up to punish or reprimand anyone involved for this. And it’s why it keeps happening.”