'I got out just in time': American, British scientists flee funding instability for Canada

While some scientists in the United States are preparing to march on Washington under the threat of funding cuts from President Donald Trump's administration, others aren't waiting to see where the chips fall and are heading north to Canada.

Athan Zovoilis is new to the University of Lethbridge, having landed in the southern Alberta city in January after working for nearly five years at Harvard Medical School. He is an assistant professor of bioinformatics and genomics, as well as a candidate for a Canadian Research Chair position.

Recent reports have signalled that an onslaught of foreign-trained academics might be on the way for Canada's post-secondary institutions. Zovoilis says there's no waiting involved — the brain gain is already in the works.

It's not just Americans fleeing funding instability, it's also British researchers living in a post-Brexit world.

Trump drags politics into science

"I wouldn't say that Trump's election itself was the reason I left, I had made my decision before to come to Canada. But having said that, some policies that seemed likely to be implemented with the new administration, especially funding for research, did strengthen my decision to leave the U.S.," Zovoilis told CBC News.

Typically scientists try to stay as far away from politics as they can, Zovoilis explained, at least publicly. In the case of Trump, it's hard to keep the two separate.

Trump hasn't made a secret of his distaste for funds doled out to the scientific community. His first proposed budget, revealed last week, slashes research funding including a $5.8-billion cut to the country's National Institutes of Health (NIH), which funds the country's foremost medical research centres looking at cancer and other diseases.

When talking to his colleagues who remain in the U.S., Zovoilis says he can hear the frustration and anxiety mounting.

"A reduction in NIH funding could lead to mass layoffs, could harm young investigators who have no chance to get initial funding, and that's definitely a huge concern."

But the United States's loss could be Canada's gain. Zovoilis says as he's been hiring research students and postdoctoral fellows, most applicants have been from the United States.

This week he interviewed a woman from one of the premier American cancer research centres. Zovoilis said the woman disclosed that she is looking for work elsewhere because, as a member of a minority, she no longer feels welcome in that country.

Scientists Brexit to Canada

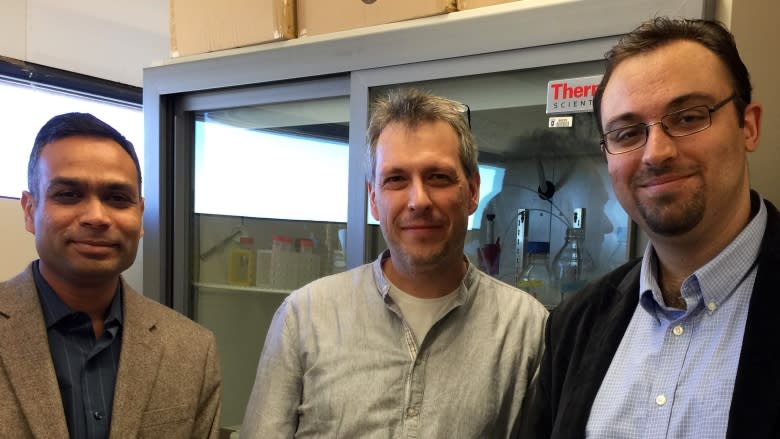

Trushar Patel, an assistant professor in medicinal biophysics, is originally from India. He spent years researching in the U.K., before making the move to the U of L last spring, where he now works with Zovoilis in the Alberta RNA Research and Training Institute (ARRTI).

Patel left the U.K. months before the Brexit referendum vote even took place, but he said former British Prime Minister David Cameron's re-election in 2015 was enough to worry him, because of Cameron's campaign promise that a referendum would be held.

"When [the University of Lethbridge] announced the position here that I could actually fit in, I applied immediately," Patel said.

"I was lucky, I got out just in time."

Patel says in conversing with his colleagues and mentors on the far side of the pond, his relief is reinforced as they face years of uncertainty.

"They've started these multimillion-dollar projects and either the money is halted, or they don't foresee any money coming in. So all the investment they've done in training, in research, is going to be stalled or not be productive at all."

That stands in stark contrast to the bright future he sees for himself and his colleagues at the U of L.

"Over the next decade, this industry, biotech industry, is going to be a multi-billion dollar industry. And we will have a huge shortage of skilled people in Canada, let alone the world. So our goal is to train those people coming out of this university with diverse backgrounds, trained by the smartest of the smartest people, and put them into a workforce in Canada."

Lethbridge punching above its weight in infrastructure

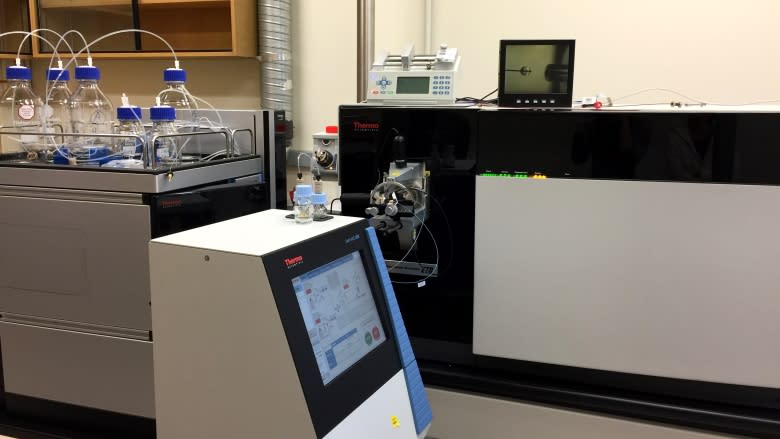

Both Patel and Zovoilis said the impressive level of infrastructure at the University of Lethbridge, as well as the promise of stable and secure funding, were key factors in their decisions to come to Canada.

Their department has managed to create what they call a "maker space" at the school where their researchers can come and use millions of dollars of equipment before they've secured grant funding of their own.

Hans-Joachim Wieden, the director of the ARRTI, says the infrastructure in that space has directly influenced the decisions of the last three hires in his department, as well as hires in other departments that share use of the facility.

"It provides access to state-of-the-art infrastructure, and it's shared infrastructure," Wieden said, which goes against the norms of how research equipment is typically purchased and used at universities.

The lab has already been used in the infancy stages of three different companies, Wieden says, and can be used for medical and agricultural research.

Zovoilis says he hopes that Canadian universities capitalize on their research investments and make the international academic community aware that this is the place to be.

- BUDGET 2017 | Government offers incentives for innovation

- MORE ALBERTA NEWS | Alberta woman loses foot, toes, fingers after rare strep A infection