Hard At Work: Why this city employee says years of contract work led to her mental breakdown

When Victoria Muir was hired by the City of Toronto as a camp counsellor in 2003, she thought she "hit the jackpot" with a "dream job."

Working her way up, the Queen's University graduate landed a contract in 2006 as a community recreation programmer whose job duties included time in at-risk neighbourhoods, home visits with Syrian refugees and women fleeing abuse.

Muir worked full-time hours, but under the part-time collective agreement, doing something she said was her purpose in life.

She was happily married and her husband also worked for the city at the time. They bought a home in the east-end and were looking forward to having kids — but putting it off until they had more work stability and benefits.

More than a decade later, working contract after contract without benefits or sick days — Muir suffered a mental breakdown and a miscarriage within the same week.

"The culture is keep your nose to the ground," she told CBC Toronto from her home. "Work hard and eventually you'll get your permanent contract."

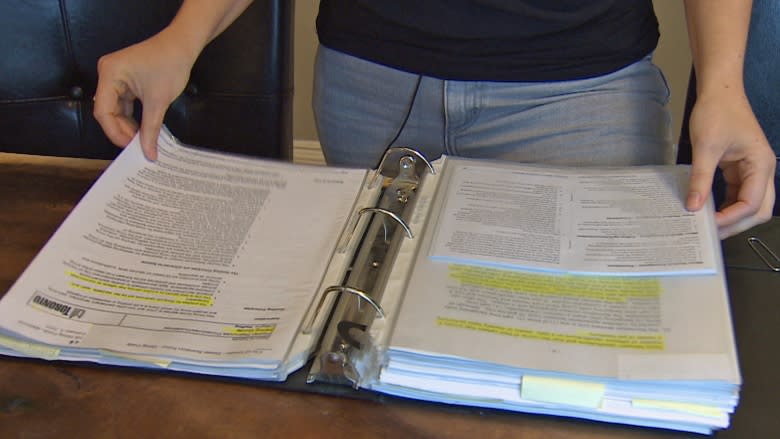

Muir is speaking out, she says, because she doesn't want to see any more young workers forced to endure part-time, temporary contracts. She has provided extensive documentation of her work history and her grievance process with the city, which CBC Toronto has reviewed.

'Strong and confident' worker

Muir says she was very good at her job and won several awards on behalf of the city for the work she did. One of Muir's co-workers spoke to CBC Toronto under condition of anonymity and echoed this, saying Muir was passionate and an excellent worker.

"People didn't believe I was capable of having a mental breakdown because I was so strong and so confident," said Muir.

"I think I started showing signs of strain and stress about year four or five but didn't understand what was happening to me," she added. "I would be leaving meetings feeling like I was having a heart attack but I just stayed with the culture to work hard, stay quiet and not complain."

Muir eventually did complain — along with eight other Parks, Forestry and Recreation department workers also on "Acting Assignment" or "Alternate Rate" contracts in 2012. They filed a grievance with their union in an effort to move their types of contract into the full-time collective agreement — which would provide benefits and support. They were offered an $800 settlement instead, five years after the grievance, which Muir refused.

Tim Maguire, CUPE Local 79 president, says these types of contracts are hard for the workers because they "feel like they are going to get kicked out of the job at any time."

When Muir and her co-workers raised the issue of stress with their supervisor, the solution was to bring in a public health nurse who would provide "vicarious trauma" training.

The nurse's advice to her was to "take your vacation days and make sure you use all your benefits," Muir said.

Muir says the nurse couldn't understand when she told her they didn't receive city benefits or sick days in their type of contract.

Full-time permanent position

Eleven years after starting with the City of Toronto, Muir was offered a full-time, permanent position in 2014 after going through the hiring process — which included an interview and exam.

"I believe that's what started bringing on my mental breakdown for me," said Muir about the hiring experience.

Muir remembers the day it happened vividly.

"I was sitting in my basement and I was thinking … 'I got my permanency, I feel like there should be a weight lifted off my shoulders, this is everything I've been working for,'" she recalls.

"I literally paralyzed myself. I couldn't move."

She called her husband who told her she would be okay. When he came home six hours after that call, Muir was still on the floor.

Mental disorder diagnosis

When she called the city's human resources department she was told she didn't have access to her vacation yet, but could use her sick days. She was diagnosed with Major Depressive Disorder, Adjustment Disorder and Anxiety Disorder, of which the precipitator was workplace stress, according to her doctor. She was eventually granted long-term sick leave.

In accordance with city policy, Muir has continued to provide doctor's notes stating she is unable to return to work, but in November 2016, her Long-Term Disability payments ended, something Muir said forced her and her husband to refinance their house.

This happened after the city asked Muir to be assessed by a third-party psychiatrist, who did not agree with the doctor who had been treating her for more than two years.

In an email to CBC Toronto, a city spokesperson said "the goal of [Long-Term Disability] benefits is to provide adequate income replacement for employees who are totally disabled" and that they have separate provisions for short-term disability and illnesses.

At the end of March, Muir received a written letter from the city stating they are not "agreeing that [she is] unable to return to work."

"I hear again that the city doesn't believe me that I suffer from anxiety and panic and depression," she said about the letter. "I hear that they think I'm lying."

One of the main issues surrounding mental health in any workplace, according to Jeff Moat, president of Partners for Mental Health, lies in treating employees with mental illnesses with a degree of respect and understanding.

"Imagine if you were to tell someone that was diagnosed with cancer that their illness isn't real ... it's ludicrous. Yet because it's a mental illness that's the norm," said Moat, whose organization launched a workplace mental health campaign called Not Myself Today five years ago.

Health forms are for physical abilities, not mental issues

The form Muir's doctor had to fill out was created in 2004 and does not include space for mental illness or disease. The criteria is limited to physical abilities including lifting, pushing, sitting and climbing — things which won't necessarily affect someone with depression.

Moat says any form that has a physical illness component should also include mental illness.

The city said it does "not speak to HR matters" and would not be able to speak directly about Muir's case "due to privacy matters."

But the city did say it is "committed to actions that prevent harm to employees' psychological health in its policies, programs and services."

Muir's message to the city is a simple one — stop this type of contract.

"I'm a person, I'm not a pawn in some kind of collective agreement," she said. "I really hope they understand that my life, my life path, my family life, my life with my husband has been changed forever."

Do you want to share your workplace story? Email us.