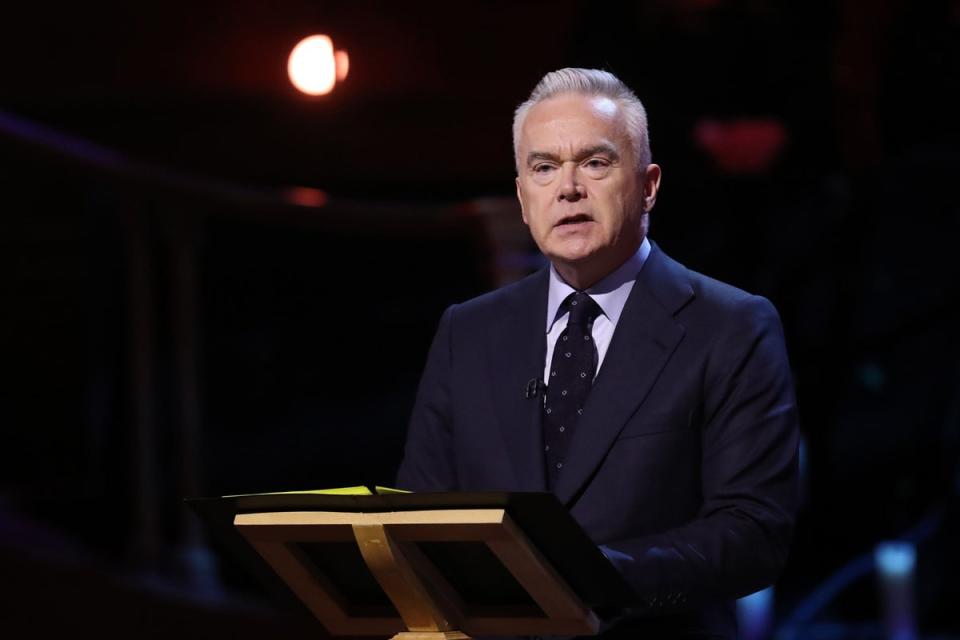

Huw Edwards: From breaking the Queen’s death to his sex scandal and BBC resignation

When the unthinkable, yet inevitable, happened in September 2022, the eyes of the nation fell on one man. “BBC television is broadcasting this special programme,” croaked the clearly emotional tones of Welsh newsreader Huw Edwards, “reporting the death of Her Majesty the Queen.” It was a moment of national grief, one that closed the book on a volume of British history. And it was all filtered through the prism of one man who seemed singularly able to capture the moment, in all its solemn gravity.

Today, the BBC announced that 62-year-old Edwards is resigning from the corporation, citing “medical grounds”. Edwards has been off-air since July 2023, following the revelation that the presenter was embroiled in a sex images scandal. After the news broke, amid a flurry of tabloid curiosity, Edwards began hospital treatment for serious mental health issues, leading his wife, Vicky Flind, to release a statement announcing that her husband had been treated for severe depression in recent years. “The events of the last few days have greatly worsened matters,” she wrote, back in July. “He has suffered another serious episode and is now receiving inpatient hospital care where he’ll stay for the foreseeable future.”

The revelation rocked both his industry and the nation’s confidence. Over decades in the business, Edwards – in his unshowy way – became the man most capable of expressing the stolid rationalism of British emotion. His fall from grace shook something at the core of their identity. How did it all go so wrong?

Born in Bridgend in 1961, the son of Hywel Teifi Edwards, a prominent academic of the Welsh language, Edwards’ career at the BBC began in 1984. Self-described as “very swotty” in an interview with The Guardian, Edwards had completed a postgraduate degree in medieval French and achieved Grade 8 piano by the time he joined the Beeb as a trainee. Within a few years, he was a political correspondent for BBC Wales at the age of 25 (the youngest in the corporation’s history), and, in the 1990s, became a newsreader on the Six O’Clock News, the BBC’s flagship early-evening bulletin. Following in the footsteps of luminaries such as Jeremy Paxman, John Humphrys, Moira Stuart and Sue Lawley, he was, until his resignation, the most experienced presenter on the show’s roster.

The News at Six (the name was refashioned in 1999) was, until 2006, the most widely watched news programme in the UK, when it was overtaken by the News at Ten, on which Edwards is the main presenter. Both programmes remain among the top-ranked news bulletins, each boasting audiences of several million households, giving Edwards an almost unique opportunity to speak directly to living rooms across England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland.

From 1994 to 2023, his near-30-year tenure as a primetime newsreader has seen Edwards cover some of the most important news events of our lifetimes. “America is pounded in the world’s biggest terrorist attack,” Edwards told the nation at 6pm on 11 September 2001. Through the Nineties and Noughties he was the man who articulated to British audiences the defining news stories, from the “war on terror” to natural disasters like the Boxing Day tsunami and Hurricane Katrina. In 1999, he was part of the team covering the murder of fellow Six O’Clock News presenter Jill Dando, which shocked the nation.

And then, in 2010, he stepped up to the big league.

His selection to anchor the televised proceedings at the wedding of Prince William and Kate Middleton cemented his reputation as “the country’s new master of ceremonies”. A calm, unfussy presence in the commentary booth, his performance on that big day back in April 2011 saw him secure the gig to provide coverage of the wedding of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle, not to mention the Queen’s funeral and the King’s coronation. Like Bollinger, Burberry and Barbour, he appeared to be stamped with the royal warrant.

“This is what it’s all about,” he told viewers, as William and Kate slipped along The Mall in a gilded carriage. “This is what the great British pageant is about.” For a phlegmatic Welshman – who looks like a former rugby player – Edwards instinctively understands the relationship of the British proletariat with its royal masters. Sitting between the sycophancy of the palace commentary corps and the cynicism of republicans, Edwards has a natural capacity to parse events as history. Whether it’s wedding bells or breaking news, his lilting voice tells audiences to keep their eyes glued to the screen.

Despite his academic background in the humanities, Edwards became an increasingly prominent part of the BBC’s political coverage. The trust that the corporation held in him was demonstrated in 2019 when he was chosen to replace David Dimbleby – the long-standing compere of election nights – as the anchor of the BBC’s general election coverage. Just as when he announced the death of the Queen, it was a huge role, fraught with the burden of delivering a historical moment. “Our exit poll is suggesting that there will be a Conservative majority,” he told viewers as Boris Johnson swept to victory. “The biggest Conservative majority since Margaret Thatcher’s third victory back in 1987.”

In the London-centric world of British politics, Edwards has been a rare and strong regional voice. A fluent Welsh speaker, he has frequently broadcast in his native language, as well as producing a documentary series for the BBC, The Makings of Wales. “This is our story,” he told viewers, perched on a cliffside on the Gower peninsula, “the story of Wales.” His father Hywel had in 1983 contested the seat of Llanelli for Plaid Cymru, the Welsh nationalist party, finishing a disappointing fourth. Edwards the younger completed a PhD in 2018, submitting a doctoral thesis, in Welsh, looking at 300 years of Welsh dissidents who, like his family, had hailed from Llanelli.

Despite being raised in this fiercely Welsh environment, Edwards chose the path of scrutiny rather than activism. All the same, he got into hot water in 2022 after he branded a Telegraph op-ed about Mark Drakeford, the first minister of Wales, “feeble”. “I thought ... writers had moved beyond sheep and Richard Burton,” he tweeted, before adding: “Duw â’n gwaredo”, meaning “God will deliver us”.Like all the best newsreaders, part of the Edwards mystique has come from his involvement in flubs and blunders. In 2017 he spent over 2 minutes live on air without noticing it, thanks to technical failures in the BBC studio. Also assisting his reputation was the revelation – via a Twitter meme – that he started each evening’s broadcast in the same, left-leaning position, which spawned a viral supercut.

Then there was the moment in the 2022 local elections when he was caught eating a croissant in the small hours of the morning. “I’m going to admit to you I’ve just had a little bit of croissant,” he told viewers, wiping crumbs from the corners of his mouth. “So I’m just finishing it, and I’m ashamed to say that, but there you go.” It was the sort of cuddly moment that validated the general perception that he was, as the kids would say, an unproblematic fave.

The combination of gravitas and whimsy held him in good stead as he stewarded the transition between the Elizabethan and Caroline eras. “When Huw Edwards gets home, do you reckon he can’t stop narrating,” one tweet, by @ultrabrilliant, said. “The fridge there, of course ... a great thing for keeping liquid cold, as it has done for many years. The milk, a favourite of her late majesty, now ... into my tea.” (That tweet has been “liked” more than 65,000 times.) For a corporation rocked by a decade of sexual and criminal scandals – from Jimmy Savile to Rolf Harris, Stuart Hall to Chris Denning – Edwards was a standard-bearer for hard work and application.

For better, but often for worse, the BBC has afforded its news staff a degree of privacy not usual for personalities with their level of celebrity. Edwards, who is married with children, lives in leafy south London, away from the hustle and bustle of media scrutiny – and from accusations of north London liberal bias.

In 2021, he addressed his struggles with depression in a Welsh-language documentary for S4C. “I can’t tell you that there’s a trigger for this or a trigger for that,” he later told the BBC’s Access All podcast. “I’ve had bouts of depression and I honestly can’t give you a trigger.” The depression, he said, had left him bedridden for periods. “Things that you usually enjoy, you dread,” he told former Labour spin doctor Alastair Campbell in an interview for Men’s Health. “You come into work, and obviously you do a professional job, but you’re kind of pushing your way through it.”

To find an outlet and deal with these feelings, Edwards relies heavily on physical exercise. He boxes regularly with Clinton McKenzie, who represented Britain at the 1976 Montreal Olympics, at a gym behind Dulwich Hamlet Football Club. He is also a regular congregant at Jewin, the Welsh Presbyterian church just off the Barbican estate in central London. During a campaign to save the church, the oldest Welsh-language place of worship in London, he described it as a “home away from home”.

But for all this outward projection of responsibility and family values, Edwards evidently struggled with fame and wealth. The BBC’s pay disclosures in 2023 revealed that Edwards was on an annual salary of £435,000, meaning that, among the male staff at New Broadcasting House, only Gary Lineker and Alan Shearer out-earned him. These controversial pay scales came under further scrutiny after the allegations about Edwards’ transfers of cash to a vulnerable teenager. Now, as he leaves the corporation, it might be seen as an opportunity for the BBC to reappraise these pay scales and try to avoid similar headaches in the future.

“Failure and setbacks are a part of life,” Edwards told an assembled crowd of students as he delivered the Philip Geddes memorial lecture in Oxford, just a few weeks before his face was plastered across every newspaper in the country. “They’re not the end of life.” As Edwards looks ahead to his post-BBC future, he would be well served by his own advice. Public opinion – which was once so firmly consolidated in his favour – is split. But what started life as a salacious media whodunit has transformed into something more sympathetic, more retrievable. The end of a difficult and sordid chapter, undoubtedly, but not, perhaps, the end of the story.