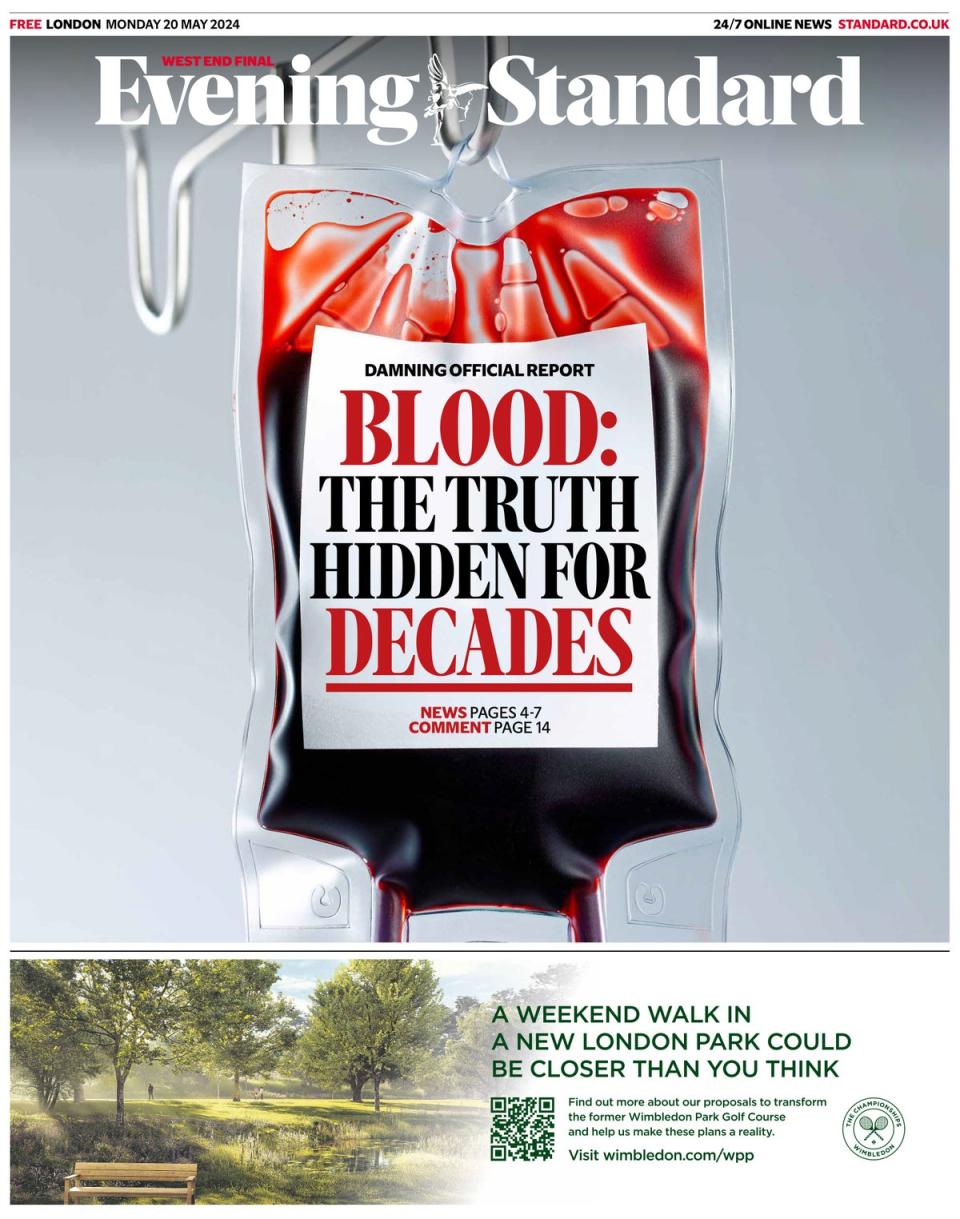

Infected blood scandal: 1,000s of victims knowingly exposed to 'unacceptable' risks, scathing report reveals

You can hear more about this story on The Standard podcast.

The biggest treatment scandal in NHS history could have been largely prevented but the truth was hidden for decades by a Whitehall cover-up and a litany of other failures, a scathing report found on Monday.

The long-awaited Infected Blood Inquiry’s report told in withering terms how tens of thousands of patients were “knowingly exposed to unacceptable risks of infection” from the 1970s into the early 1990s with “shattering” impacts on their lives.

People were “cruelly” told they were getting the best treatment available and ministers refused to take responsibility to “save face”.

At least 3,000 out of more than 30,000 people infected with contaminated blood products or through tranfusions have already died and the “number is climbing week by week”.

Inquiry chairman Sir Brian Langstaff said: “Lives, dreams, friendships, families, finances were destroyed.

“This disaster was not an accident.

“The infections happened because those in authority, doctors, the blood services and successive governments, did not put patient safety first.”

Instead, they were given contaminated blood products including Factor VIII, mainly shipped from the US, from donors who often included prisoners and drug users.

Thousands of families across the UK were affected by the scandal with someone infected with Hepatitis or HIV, with the “physical and psychological pain, stigma and grief still being felt today”.

People who survived were “robbed of years of healthy life” and their partners, family and children had their lives ”fundamentally changed”.

More than half of the boys treated for haemophilia at Lord Mayor Treloar College, Hampshire, a boarding school for children with disabilities which had a specialist NHS haemophilia centre on site between the 1970s and 1980s, are now dead.

The 2,500-page report concluded that the “chief responsibility” for the overall failings lay with “successive governments” including the administration of Margaret Thatcher.

She told a No10 meeting in November 1989 that people infected with HIV from blood products “had been given the best treatment available on the then current medical advice, and without it many of the haemophiliacs would have died”.

The report also stressed that other people and organisations outside of government share some of the blame.

It highlighted a letter by epidemioligist Dr Spence Galbraith in May 1983 to a Health Department official advising that “all blood products made from blood donated in the USA after 1978 should be withdrawn from use”.

How the scandal unfolded

Tens of thousands of people were infected with HIV and/or hepatitis after they were given contaminated blood and blood products between the Seventies and early Nineties.

It is thought that one person dies as a result of infected blood every four days. Some 3,000 have died and others have been left with life-long health complications.

There are two main groups of victims — people who needed blood transfusions and those with bleeding disorders such as haemophilia who needed blood, or blood products, as part of their treatment.

Haemophilia is an inherited disorder where the blood does not clot properly.

In the Seventies, a new treatment was developed — factor concentrate — to replace the missing clotting agent, which was made from donated human blood plasma.

Manufacturers pooled plasma from tens of thousands of people — increasing the risk of the product containing blood infected with viruses including hepatitis and HIV. People with haemophilia were treated with British and American blood products.

A shortage of UK-produced factor concentrate meant clinicians relied on imports from the US, where people in prisons were paid to be donors, despite being at higher risk of carrying infection.

Victims were infected with hepatitis C, HIV and hepatitis B. A small number contracted Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease.

Then PM Theresa May ordered the inquiry in July 2017 after years of campaigning by victims and their loved ones.

Some 374 people have given oral evidence, and the inquiry has received more than 5,000 witness statements.

Interim compensation payments of £100,000 have been made to around 4,000 people or bereaved partners. Ministers have announced that these payments will be extended to the “estates of the deceased”.

Calling for a “change of culture and practice in the NHS and the Civil Service” so such a scandal could never happen again, the report flatly rejected the argument that its findings were a “question of hindsight”.

It emphasised that “Government decision-making was slow and protracted. ‘Doctor knows best’ was such a strong belief that health departments did not issue guidance to curb unsafe use of blood and blood products”.

It added: “Patients were not informed of the risks of their treatment and were thus denied their rightful choice.”

Some people treated with blood products, including children, were “further betrayed” by being used in medical trials without their knowledge or informed consent.

Suffering of victims was “compounded by the reaction of successive governments, the NHS and the medical profession,” including delays and destruction of documents in the Department of Health.

Concerns were raised that Aids and HIV were not being put on death certificates in an attempt to “cover up the truth and protect doctors”.

The report added: “Standing back and viewing the response of the NHS and the Government the answer to the question ‘was there a cover-up?’ Is that there has been.”

It stressed that there was not an “orchestrated conspiracy” to mislead but there was a cover-up in “a way more subtle, more pervassive and more chilling in its implications.”

'Justice for those still with us. But for so many it has come too late'

Richard Angell is chief executive of Terrence Higgins Trust

Today campaigners have been vindicated with this final report by inquiry chairman Sir Brian Langstaff. But, crucially, they have still not been compensated.

For four decades the contaminated blood scandal has blighted the lives of so many — lives lost, families pulled apart, trauma lived and relived. For four decades people have fought their own doctors, NHS and governments for the details of today’s final report and the redress that should rightly follow.

Survivors watched with open mouths, relief and tears — both of grief and exhaustion — as Sir Brian set out the lies, deceit, obfuscation and cover-up involved in the biggest treatment disaster in the history of the NHS.

That’s why today is such a seismic moment for those infected and affected by this horrifying scandal. But they represent such a small proportion of those impacted — they are the living. The 225 people with HIV from contaminated blood products able to watch today represent just one in five of those who were infected in the Eighties. While they have all experienced Aids — and somehow survived — the rest are gone. But they will never be forgotten, including many of their partners, parents and children who have tragically died too.

Those remaining have not only experienced avoidable grief but also a generation of avoidable fighting for justice, which has consumed so much of their time. Someone affected by this heartbreak dies every four days. My message to Rishi Sunak is this: let no one else die before you stand in the House of Commons and apologise on behalf of your government, your forebears and right these wrongs. Rather than decisions around compensation being made behind closed doors by unnamed experts, the Paymaster General needs to expedite the work and be transparent and open about what is happening.

A final compensation deal has not been offered to victims. It is only those living with HIV or hepatitis C or their widows who have received a penny in interim payments. The Government has been dragged kicking and screaming for every bit of updated information.

For those who die between now and finally getting their compensation, everything must be done to ensure it isn’t the Treasury who holds onto the cash. Every person who watched today and has a rightful claim should be able to sleep tonight knowing they have provided for their family.

Today must be the start of the end for this long, painful campaign for justice. But, for everyone hoping to cut corners, row back or delay, know this — the campaigners involved in this scandal never give up. And neither will I.

The report, which could not recommend prosecutions, found that a “lack of openness, transparency and candour” from the NHS and Government meant that the truth about the scandal was “hidden for decades”.

Prime Minister Rishi Sunak was expected to issue a formal apology.

Several governments are blamed for the scandal, with former Health Secretary Lord Ken Clarke criticised for his comments to the inquiry, some of which were “unfairly dismissive and disparaging towards” victims.

A compensation scheme, expected to cost around £10billion, is due to be unveiled on Tuesday.

The inquiry’s key findings included:

For both HIV and Hepatitis C, the testing of blood donated in the UK was not introduced as quickly as it could have been.

Commercial factor products, the blood products imported to treat many people with bleeding disorders, were unsafe and should not have been licensed for use in the UK.

Doctors treated patients with increasing volumes of factor concentrates despite the known risks of viral transmission and without informing them of those risks. They gave false reassurance to patients.

It was apparent by mid-1982 that there was a risk that the cause of AIDS could be transmitted by blood and blood products, but the government failed to take steps to address that risk.

A decision in July 1983 not to suspend importation of commercial concentrates was wrong.

Research was conducted on patients with bleeding disorders, including children, without telling them, or their parents, beforehand, or informing them of the risks.

The repeated use by government of inaccurate, misleading and defensive lines to take, which included cruelly telling people that they had received the best treatment available.

As Prime Minister, Theresa May set up the inquiry in 2017.