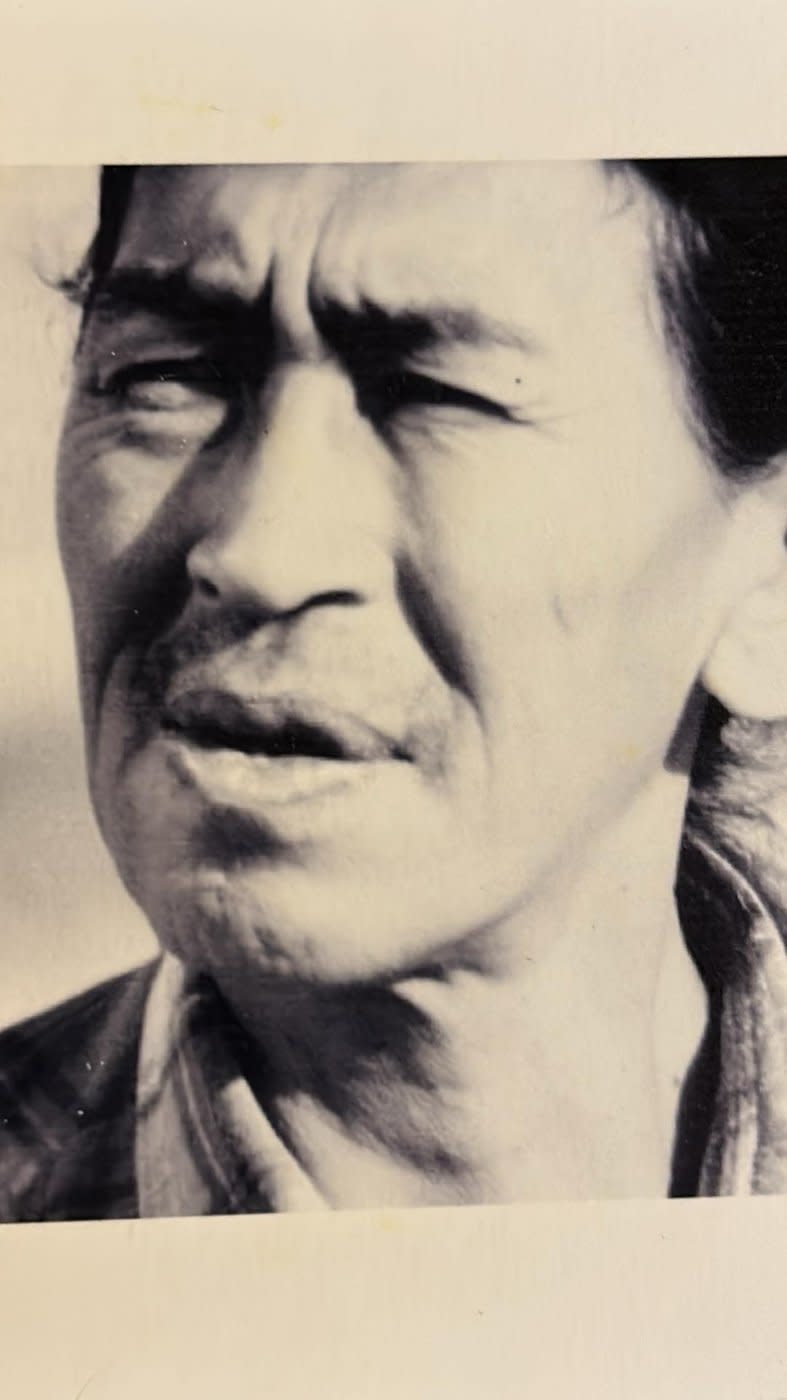

Inuk filmmaker Mosha Michael: "Something to look at"

Raigelee Alorut has a whale of a story to tell about her brother who just happens to hold a special place in Inuit lore.

Mosha Michael, the oldest of nine siblings, was born in an outpost camp in Apex in 1948. He's recognized as the one of the first Inuk filmmakers and is described by his sister as a sensitive, artistic soul, reflected in his short films which “are imbued with a rare precision and poetic intimacy, underlining the artist’s close relationship with his subjects.”

In time for National Indigenous Peoples Day on June 21, the National Film Board of Canada (NFB) has re-released Michael’s 1977 film Natsik Hunting, a short documentary of a beluga whale hunt in Frobisher Bay set to Michael’s own music.

“Oh yes, I remember him singing,” says the now 60-year-old Alorut in an interview with Nunavut News. “I remember him playing guitars back then. I remember he was really into music. It was hard when I first heard Mosha’s voice after he passed away, when he was singing. Sometimes I’m still worried about turning the page.”

Turning the page on difficult history

Alorut herself was born in 1964, and her early memories are mostly of the coming and going of family members like Mosha from North to south, shuttled between Hamilton, Ont., and Churchill, Man., for long periods of tuberculosis treatment and residential school.

“This was never talked about in the family,” she says of their experiences and absences. “They were gone one day, and they came back one day. We tried to stay close together as a family."

Alorut ended up in her aunt’s care in Iqaluit in her formative years after the death of her mother around age nine.

“After that, our family broke apart," she said.

After graduating from Churchill Residential School in Manitoba at age 16, Michael returned to Iqaluit for a short period before his permanent move south. It was before this, in 1974, that Michael took part in a Super-8 workshop led by the NFB. Within a year, he released Natsik Hunting along with a soundtrack co-composed and performed by artist Etulu Etidloie.

With no extant catalogue of his work, it's difficult to estimate the full range of Michael’s artistic output. The NFB credits him with three short films: Natsik Hunting (1975), Asivaqtiin/The Hunters (1977) and Qilaluganiatut/Whale Hunting (1977). Afterward, Michael worked for the Inuit Broadcasting Corporation.

“With his short films that he had, I remember [at] the Inuit Tapiriit [Kanatami] building it was announced that my brother Mosha was going to introduce his films, and we were all excited to go see them,” recalled Alorut.

In 1985, Michael relocated to Toronto to further pursue his film career. It was around that time Alorut lost contact with her eldest sibling, apart from reuniting briefly as a family for their father’s funeral, until she, her husband, and her son moved to Toronto in 2003.

“It was good to see him and everyone, it was good to get connected,” said Alorut, who relocated to Toronto to pursue higher education.

By this time, most of the Michael siblings were living in Toronto, although Alorut said her brother socialized more with their other brothers.

“We would see each other then and now, not often," she said. "Mosha got sick and it was harder to interact.”

Alorut recalls that Michael spent a lot of his time and energy “carving soap stone, and he used to do some little gatherings with the schools. Maybe doing some programs about his carvings. When he got sick, he couldn’t do it anymore.”

By this time, Michaels was supporting himself by selling his carvings.

Alorut said that despite securing funding from the NFB and what was then called the Department of Indian and Northern Affairs to make his three archived short films from the 1970s, Michael was never able to get the money together to continue his filmmaking down south, so he turned to carving to survive.

“You need money to be what you want to be (and) carving was in our blood,” she said.

Hunting is a predominant theme in many of Michael’s films, as the family was, according to Alorut, taught “informally by my father. Mosha enjoyed hunting, surviving out on the land. That’s what he loved.”

Asivaqtiin/The Hunters documents Inuit inmates from Iqaluit’s penitentiary being rehabilitated by spending time learning traditional practices out on the land.

'Something people can look at'

When asked why Michael never came back to Nunavut, Alorut didn't know.

“I don’t know if he got stuck down there. It’s hard to know," she said. "Maybe it was cheaper [to live], and his daughter was there.”

By this point, Michael had dropped out of photography studies at Ryerson University (now called Toronto Metropolitan University), married, and had two children. He was also struggling with addiction and ended up dying homeless.

“He went downhill after residential school,” recalls Alorut. “I don’t know how he survived. He survived when other kids did not. He made it home. Other kids did not make it home. They were killed by residential school. All these survivors, they have addiction problems, but he was kind. I remember he was very kind. He was very sensitive.”

All the siblings living in Toronto were present for Michael’s passing in 2009, gathering together by his bed at St. Michael’s Hospital. Lacking the necessary funds, and having to go against Inuit tradition, they had his body cremated and shipped back to Iqaluit after a ceremony at the Native Canadian Centre, where Michael was “well-known to those people.”

A family friend arranged for the remains to make their way North via their sister Annie, where they were scattered in the Apex River.

“That’s so sad,” says Alorut, but who is also happy that her brother was eventually brought back to Nunavut, where a ceremony and prayers that included his friends and family were performed.

“He’s home. He’s home now.”

Alorut makes it clear that she does not want her brother’s struggles with addiction to be the focus. It’s his work as an Inuk filmmaker, a title his sister wasn’t even aware of until recently, that will be remembered.

As it should be.

Kira Wronska Dorward, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter, Nunavut News