In Inukjuak, Que., voting seems futile for community members who feel ignored and forgotten

Sitting at her dining room table in Inukjuak, Siasi Smiler Irqumia gets straight to the point.

"Things don't really happen, even if we vote."

"We are just another community in Quebec," says the Inuk elder — deserving of attention.

"But when I look at the Inuit people, Cree people, Naskapi, we are very much avoided. Our communities are avoided."

There's anger in Inukjuak, one of the villages in Quebec's Nunavik region, and disappointment, ahead of the provincial election on Oct. 3. Why pay attention to it, they ask, especially when history proves residents' needs won't be met?

It's a common refrain among those in the Inuit community of about 2,000.

At their dining room tables, or along the beach facing Hudson Bay, at the medical dispensary or the community centre, Inukjuak community members express their worries about the village, along with their love for it.

WATCH | Inuit community members describe their frustrations with this election:

"It's home," Irqumia says, watching as her grandson makes breakfast and her daughter feeds her granddaughter.

"I know everybody. I know the history."

Largest geographic riding, fewer voters

The Ungava riding is Quebec's largest geographically, extending from the province's northernmost village of Ivujivik to Chibougamau, 1,400 kilometres south of there.

Still, it has fewer eligible voters than most other ridings, and voter participation is often the lowest in the province.

In 2018, voter participation in Ungava was 30.89 per cent compared to the province's overall turnout of 66.45 per cent, according to Élections Québec.

For many in Inukjuak, not turning up at the polls can't be explained so much by apathy or indifference, but by a sense they are disregarded.

"We're here just listening to the news and [the candidates] talking about what they want to be elected for, and here we are: 'What about us? Why can't we say something to you? Come to our community and see what is happening in Nunavik,'" says Phoebe Atagotaaluk, who has lived in Inukjuak since she was a teenager.

"There's so much that needs to be fixed in the North."

In Inukjuak, municipal services like delivery of potable water and removal of sewage aren't provided regularly. Kids find themselves out of school because of a lack of teachers.

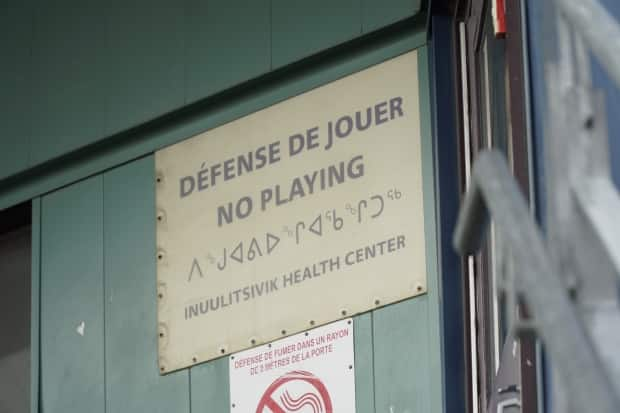

And this past summer, the only access to health care was for emergency treatment. A shortage of nurses at the local health centre meant that for some time, community members couldn't come for walk-in appointments or regular checkups.

So concerned was the Nunavik Regional Board of Health that it asked the Quebec government to send in the army, but the request was rejected.

"When we asked for the army, it was because we were really worried for the community," says Charlie Laplante-Robert, a nurse working for the Inuulitsivik Health Centre in Inukjuak.

"As the community already feels abandoned, we all felt abandoned a big deal."

Instead, the government reinforced the dwindling health-care staff in Nunavik with agency nurses, paramedics and the Red Cross.

"The backup at the moment is sadly not really helping. It's not the professionals that we need with the qualifications to do on-call care," says Laplante-Robert, adding very few have had the experience or training to work in an Inuit community.

"Emotionally, it gives a lot of stress and fear, and [community members] are also angry that they don't have the care and the services that they deserve."

No specialist doctors

Irqumia knows that sense of abandonment far too well. Four years ago, the 69-year-old was diagnosed with Parkinson's disease.

As she talks, her right arm trembles, showing signs of the disorder. Her once-steady walk is now a shuffle.

"I knew Michael J. Fox had Parkinson's, that's all I knew," Irqumia says, bursting into bright, bubbly laughter, before broaching her fears.

"[Parkinson's] is not new for the world, but it's new for our area. We don't have access to a lot of doctors, and we never have the same doctor. So it's always repeating and repeating information."

There are no specialist doctors in Inukjuak. To get semi-regular checkups, Irqumia has to make the long trek to Montreal, a five-hour flight south.

'They wait, and then wait and wait'

"This is what happens to a lot of people in our community, though," Irqumia says.

"They need to see a doctor but they wait, and then wait and wait."

For Atagotaaluk, the politicians and the people making budget and resource decisions ignore the realities in Nunavik.

"It's really sad. I love Canada but really, our government has no idea of how we are living," she says.

"What if they come to our community and live how we live?"

Sitting behind his desk at Inukjuak's municipal building, Ricky Moorhouse isn't holding back.

"Why would you vote for a government that tried to abolish you?"

The Inuk man is conflicted though, because as deputy mayor for Inukjuak, he recognizes the absolute need to work with the provincial government to ensure things in the village don't completely fall apart.

Hopes for self-government

Still, it doesn't make him any less angry.

"We are paying taxes up here. This is not a reservation. It's a community. So, there's a lot of things the government needs to provide, but they don't."

There are others, though, who reject the "southern" government and instead hope the Inuit of Nunavik can become self-governing, like those in Nunavut.

"Why do we always need people from the south that have to tell us what to do?" asks Tommy Palliser, the executive director of the Nunavik Marine Region Wildlife Board.

"There should be proper reconciliation. That's the way to reconcile: to allow us to govern ourselves."

Palliser says it's meetings like one he had with a Quebec government minister earlier this year that make Inuit not want to vote. Among the topics discussed at the meeting was Bill 96, the newly reinforced French language law.

"Why should we have a governance structure or policies in place where they are foreign languages to us? That's not respectful," he says.

"That's not representing our own people. That's kind of continuing the assimilation, continuing the colonization."

To some, though, this election does feel slightly different. For the first time, two Ungava candidates are Indigenous.

Liberal candidate Tunu Napartuk is Inuk and the former mayor of Kuujjuaq.

Québec Solidaire's candidate is Maïtée Labrecque-Saganash, a Cree activist and daughter of former MP Romeo Saganash.

Incumbent MNA Denis Lamothe is seeking re-election with the Coalition Avenir Québec. Christine Moore is running with the Parti Québécois and Nancy Lalancette, with the Conservative Party of Quebec.

"I hope [the candidates] hear the needs of our community," Irqumia says.

"I don't know if they ever step back and see what's going on in their province, so I'm really hoping they start."